Jane (not her real name) was just a regular Mississippi girl whose mother wasn't particularly focused on her young daughter. One day, an older man approached her and told her that he would take her away, put her up in a great apartment and take care of her.

"She was a typical teenager who was headstrong and not particularly happy at home," said Sandy Middleton, executive director of the Center for Violence Prevention in Pearl. "Her mother was focused on different things. Not that she was a terrible mother, but she wasn't particularly plugged in. So that helped to make (Jane) a target."

At first, the man treated Jane like he was her boyfriend. "She thought he was interested in her like a relationship," Middleton said.

The man had other ideas.

Like Jane, Holly Austin Smith thought of herself as a typical American kid. Her childhood, in a small working-class neighborhood in southern New Jersey's Ocean County, was unremarkable.

"I never went without necessities, but luxuries were few and far between," she said.

By the time she was 14, though, Smith was ready to get away from her home in tiny Tuckerton on the Little Egg Harbor. She wasn't getting along with her parents, and they argued constantly. Her mother was diagnosed with breast cancer. Smith's best friend ended their relationship. She was apprehensive about starting high school in the fall, where she believed she'd be beat up.

That summer of 1992, in her 14-year-old mind, Smith was convinced her life was over. She was aimless, depressed and felt she had no one to confide with.

Smith met Greg at a shopping mall in nearby Atlantic County where she hung out every weekend with friends.

"I noticed this guy staring at me," she said. Greg looked to be in his early 20s. (She found out later that he was in his 30s.)

"He wasn't a scary-looking guy," she said. "He looked cool; he was trendy. ... He was wearing nice clothes," something important to a 14-year-old girl.

Greg motioned for Smith to come over. At first, she hesitated, but her curiosity won out. Here was a nice-looking guy who singled her out from the crowd. After a bit of conversation, they exchanged phone numbers, and within a day, he called her.

"We talked on the phone for about two weeks," Smith said.

"He said that he could help me become a model or a songwriter or a rock star. He could introduce me to famous people," she said. "To me, (that) sounded a lot better than going to high school."

The Girl Next Door

"We have seen several cases, lately, where these individuals are trolling shopping malls and other places teenage girls hang out. They look for these vulnerable individuals," Middleton said. "It's written all over somebody's face when they're a target. We've seen this very setup, right here, time and time again."

Becoming a victim of sex trafficking can happen to those from "good" homes just as easily as it does to those from "bad" or poor circumstances. The crime cuts across all facets of society, excluding no one regardless of gender, age, race or economic status, said Heather Wagner, director of the domestic-violence office in the Mississippi attorney general's office.

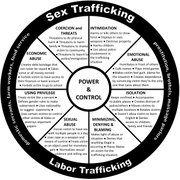

All it takes is a naive girl looking for a little affection, she said. Predators look for pretty kids whom they can easily flatter or lonely boys looking for someone who will says they love them. Once ensnared with sweet talk and gifts, it can be a short walk to doing sexual "favors" for the trafficker's so-called friends to having sex with strangers 20 times a day.

"Unfortunately, the majority of victims are the 'girl next door,'" Wagner said. Girls who look like college co-eds are in big demand among those who buy sex. "A lot of people have misconceptions" about who gets involved and how, she said. "Usually, it's a prolonged relationship" involving force, fraud or coercion.

"Traffickers take their time," Smith said. "They really hone in on your interests and concerns." She added: "I think that when it comes to kids being trafficked, it's a perfect storm. Most of the time, it's not any one issue. I think that I had some idea that (Greg) was a bad boy, but my idea of a bad boy didn't equate to a pedophile or a rapist or a sex trafficker. I'd never even heard of that term."

It's not always a stranger doing the selling or buying. "We have instances where women are sold by their intimate partner for drugs or money," Middleton said.

She also said that most trafficking victims are too afraid to speak up, or they may not understand what they're going through and don't know help is available, pushing the issue under the radar.

"These are young girls that we're talking about, for the most part," she said. "They don't understand the dynamics, they just understand that something's not right and that they're being taken advantage of."

Middleton related the story of another woman who came to the CVP for assistance, calling her Susie. In this case, the trafficker who pretended to be Susie's friend was a woman. The woman turned out to be a spy, reporting back to others, presumably men, what Susie was doing and thinking. The woman turned into a handler once Susie was in "the game." Her traffickers would move Susie based on the woman's feedback.

In Mississippi, the interstate highways make Jackson a stopping-off point for the sex trade, which is highly portable and easily propagated via the Internet. Midway between Memphis and New Orleans on the north-south axis, and Atlanta and Dallas on the east-west route, traffickers—pimps—shuttle their wares through Jackson looking for buyers.

"Jackson is the hub for the southeast, and they're bringing people from Atlanta, the northeast down through here going toward Texas or from the northwest going toward Florida," Susie Harvill, executive director and founder of Advocates for Freedom, told a seminar audience at Greater Antioch Baptist Church in February. AFF is a Gulf-Coast nonprofit dedicated to ending human trafficking.

"These are girls that are getting moved around," Wagner said.

In another case, authorities tracked a girl brought into Louisiana for the Super Bowl through a contact number on her Internet ads.

"They tracked her from (Washington) D.C., right after the inaugural ball. And she moved her way through the South snaking her way to New Orleans," she said. "Same phone number, same (headline), 'New to Town, New to Town.'"

'Turn on the TV'

By the time Greg zeroed in on Holly Smith, she had already had several sexual encounters. She had a relative who repeatedly abused her. Then, on two different occasions, older high-school boys took advantage of the pretty girl with long, soft brown hair.

In 2004, researcher Melissa Farley estimated that 65 percent to 95 percent of those involved in prostitution were victims of sexual assault as children.

Sex, for many girls, equates to love and intimacy, things usually missing in the lives of targeted girls.

"Once girls have sex, they consider themselves in a relationship," Middleton said. "... They want to be loved, and they get that all mixed up with sex."

"The bad guys don't look at it like that at all," she continued. Men will use sex to groom their victims while they make them sex slaves. "That's part of the deal."

No adult had talked to Smith about sex. Sex education in school consisted mainly of anatomy lessons, she said. Almost everything she learned about sex was from popular media. At 14, Smith believed that she had to have a boyfriend, and sex was supposed to be fun. Instead, her experiences left her anxious. Smith hadn't enjoyed any of them, and she was convinced that there was something wrong with her.

"There's this sexualization of girls in the media—from music videos to TV shows to advertising. Women are objectified, and they're sexualized everywhere," Smith said. "Turn on the radio; open a magazine; turn on the TV."

Sexualized TV content was the focus of a study released earlier this month from the Los Angeles-based Parents Television Council. The report found that primetime TV is more likely to present underage female characters in sexually exploitive scenes than adult women. The scripts framed many of those scenes as comedy.

"Sexually exploiting minors on TV—especially for laughs—is ... grotesquely irresponsible," said PTC President Tim Winter in a release.

"To a 12-year-old vulnerable girl who isn't getting a lot of influence elsewhere—or a 12-year-old vulnerable girl who grows up to be an 18-year-old vulnerable woman—who is constantly surrounded by these messages, it's easy to think that's how you're supposed to be: sexualized and (that your sex appeal) determines your value," Smith said. "That made it very easy for a trafficker to lure me away from home."

The Rules

Greg hooked Smith when he told her he would make her a star.

"He was feigning a little bit of romantic interest, but not too much," Smith said. "He was looking for what I was going to bite on. And what I was going to bite on was running away to Hollywood. I was going to see things; I was going to do things."

The day she ran away from home, Smith met Greg in another shopping mall, a little closer to Atlantic City. Hollywood, as it turned out, wasn't on the agenda.

"He took me to a motel room," Smith said, and left her with Nikki, who'd been waiting for her.

As Nikki put Smith in a red dress and did her makeup and hair, Smith believed they were getting ready to go out to a club. In retrospect, she knew that something was off. But just hours after running away, Smith went along with it. She was convinced she could go back home.

"At that point, that was my biggest problem," she said. "My parents knew I had run away."

When Greg returned, it was all business. He sat Smith down and went over "the rules." Without ever using the word prostitution, he told Smith what kind of men to talk to and that she had to make $200 an hour. She was to call him to "come home" when she reached $500.

The women that the Center for Violence Prevention works with would recognize Smith's story of shame and guilt. In Susie's case, the pimp wouldn't allow her to stop until she'd at least made enough to cover their hotel room. If she couldn't, they'd both sleep on the streets. "They feel like they close the door behind them and they can't go back," Middleton said.

"I think that I was just on auto-pilot once I realized what was going on," Smith said,

Primped and primed, Smith got into a cab with Nikki, who gave her more instructions. She should ask men if they wanted a date. If someone said yes, she was to tell him to come back with a car, ready to pay for a hotel room.

Smith and Nikki got out on Pacific Avenue in Atlantic City, on what Smith believes is the "kiddie track."

"I found myself trying to be sexy," she said, just like she'd seen on TV. She didn't know how to say no—she didn't even realize she had that option. "I had never said no to anything when it came from an older man."

It only took a few minutes before a man pulled up and asked Smith how old she was. Nikki did the talking. She told him Smith was 18, and she haggled over her price, $200. Then Nikki told Smith to go with "this old man," Smith said. "He actually told me that I reminded him of his granddaughter in the hotel room."

Everything changed for Smith at that point.

"After that encounter, my past life was completely gone. There were no thoughts of, 'I need to find my way back home and back to middle school,'" she said. "That was gone. I was just dealing with the present moment and transitioned into the person I needed to be."

That person was a prostitute. Though the first encounter was the worst, there were others. "I met the quota that I needed to make," she said.

The next night, a police officer spotted her. He asked how old she was, and Smith told him what Greg and Nikki had told her to say.

"I was scripted to give a different age and a different name," she said. "He bought it and was walking away from me."

Smith called out to him. "What if I was under 18?" she asked.

She was looking for options. Smith didn't want to be out on the street, but she didn't want to go home, either. "I didn't know what I wanted," she said.

The cop arrested her.

'Some Dirty Thing'

In 2000, Congress passed the Trafficking Victims Protection Act. Sex trafficking, the act defines, is when a commercial sex act is induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or when the person induced to perform such an act is younger than 18. Trafficking includes "recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for labor or services, through the use of force, fraud, or coercion for the purpose of subjection to involuntary servitude, peonage, debt bondage, or slavery." Physically transporting a person from one location to another is not necessary for the crime to fall within the definition.

Under federal law, authorities should protect trafficking victims, not criminalize them; however, many state and local laws make prostitution, pimping and buying sex illegal, and the women—the victims—are the ones usually arrested.

In 2003, about 92 percent of prostitution-related arrests in Boston were women, and only about 8 percent of arrests were men, reported Donna M. Hughes, a professor of women's studies at the University of Rhode Island in 2005. Similarly, 89 percent of arrests in Chicago between 2001 and 2004 were women, 9.6 percent were men and 0.6 percent were pimps, Hughes wrote in "Combating Sex Trafficking: Advancing Freedom for Women and Girls."

Ranked just behind weapon sales, human trafficking is the second-most lucrative illegal market in the world, with an estimated annual value of more than $30 billion.

"The United States is a source, transit and destination country for men, women and children—both U.S. citizens and foreign nationals—subjected to forced labor, debt bondage, involuntary servitude and sex trafficking," reports the U.S. Department of State. Seventy-nine percent of human trafficking is sex trafficking and, in the U.S., 70 percent of sex trafficking is linked to organized crime.

"Gangs can make more money off of selling humans than selling drugs, and it's a lot safer," Middleton said. "They can sell a person 20, 25, 30 times a day, every day."

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children estimates that 100,000 to 293,000 American children are in danger of becoming sexual commodities. The average age of a child's entry into pornography or prostitution is 12, reports the U.S. Department of Justice Child Exploitation and Obscenity Section.

Getting out of "the game" isn't easy, and prostitutes live brutal, short lives. "We'll tell your parents you've been whoring," a pimp might tell a girl, or he may threaten to kill her or recruit her little sister if she tries to leave. Most are dead within seven years.

In that way, Smith was lucky. But victims of sex trafficking share many problems with victims of domestic violence: post-traumatic stress, fear, low self-esteem and lack of resources among them. Victims also face a mountain of stigma and shame and, frequently, a police record. Few organizations are prepared to deal with the complexity of victim's issues or the danger posed by traffickers.

Hours after giving her statement, the police sent Smith home in the same red dress Nikki had put her in the night before.

"(Sex-trafficking victims) need immediate after-care," she said. "After I was arrested, I didn't get any care, none at all. All they cared about was getting my testimony. ... I was completely in a state of crisis. Nobody was concerned about my well-being."

Life became even more of a struggle for Smith. "Everyone was treating me like I was some dirty thing," she said. "Everyone was treating me like I had chosen to prostitute, like that's why I ran away: to become a prostitute."

'Emptiness and Sorrow'

"These girls need immediate trauma therapy for what they've been through," Middleton said.

For Jane, like other girls the CVP has counseled, other girls in "the life" were her friends, and she had a difficult time disengaging from them. "We were trying to pull her out, and they were trying to pull her back in," Middleton said. "... People that she cared about were still being victimized every day, and she couldn't do anything about it."

Others become accustomed to a standard of living—even if they never have control over the money they make, their traffickers dress and house them and give them gifts, something they haven't experienced before. "They have to walk away from a lifestyle on top of everything else," Middleton said. "It's just extremely complicated."

Seven days after police sent her home, Smith tried to kill herself. She ended up in a psychiatric facility, where she got some treatment, but nothing related to the trafficking. "I wouldn't even hear that term for 20 years," she said.

Smith didn't know what a "normal" relationship looked like, and she became entangled with a domestic abuser. She got into drugs and alcohol, and was in and out of therapy for years. Finally, with the help of counselors, she put her energy into school. She finished high school, went on to college and graduated with 3.6 grade average and a degree in biology.

"I rose professionally," Smith said. "I went all over this country, changing jobs. I moved up quickly because I didn't have anything else. I was so empty inside. I was trying to fill it up with education and accomplishments, which is great; that's a good thing, but I was so empty inside because I was carrying this terrible secret—that I used to be a prostitute."

In 2009, 17 years after the worst 36 hours of her life, Smith met Tina Frundt, founder and executive director of Courtney's House in Washington, D.C. Like Smith, Frundt is a survivor of sex trafficking, and Courtney's House is dedicated to helping victims heal.

"I didn't really, truly come back to life until I met other survivors who had been through the same thing," Smith said. "That's when I really got my healing."

Sex trafficking victims, even if they get out, frequently feel isolated. Because of their experiences, they don't know whom to trust. They doubt anyone loves them just for who they are. "They never know if somebody's going to turn on them or tell on them," Middleton said.

Today, Smith advocates for getting help to victims—something she didn't receive for years. She is married now and lives in Virginia. She has a website, hollyaustinsmith.com, and she works as a consultant with AMBER Alert and numerous anti-trafficking organizations. She writes a weekly newspaper column about sex trafficking, and next April, Smith will publish a book, titled "Walking Prey."

"As happy as I am today, there were years of emptiness and sorrow," she said. "I think I went through all of this for a reason."

"Once victims become survivors, they become extremely powerful women," Middleton said. "That's the cool thing about offering appropriate services to these victims: They can become survivors, in time. Once they are, they're empowered to share their story, encourage others and be part of the answer—to be brave enough to walk forward and talk about what happened to them."

Because victims have come forward, she said, organizations like the CVP understand how to provide the help other victims need to survive, such as long-term therapy and intervention.

Recently, Smith spoke to kids at the middle school where she had graduated a few short weeks before Greg lured her into prostitution. The girls were dumbfounded. "The last question they asked was, 'Why am I just hearing about this?'" she said.

She urges parent to talk to their kids about what they're watching on television or seeing on the Internet. "Teach them that their value does not come from boyfriends or sex appeal." Smith said, and added:

"I didn't choose to be a prostitute. I was a victim. I was a child, and I was exploited."

Visit www.jpf.ms/sextrafficking for more info about sex trafficking in Mississippi.

Protecting Children

Help Your Child Understand Pimps' Tactics

• A pimp will often single out a girl or boy who appears to be alone, apart from the crowd or without parental support or care.

• A pimp does not typically look like a pimp, but rather like an attractive, fun, engaging and trustworthy person.

• The mall has become one of the most common places for pimps to target pre-teens and teens.

• A pimp will tell your child that he or she is beautiful, smart, unique and (often) misunderstood. A pimp will do everything possible to gain the trust of your child.

• The seduction of your child may take months; but the pimp is patient, considering this as a business investment.

What Parents Can Do

• Check your teens' phone. Know who they are calling and monitor text messages.

• Monitor your teens' Facebook, Instagram and Twitter accounts and have their passwords.

• Know the children your kids are hanging out with—and their parents.

• Always have a chaperone with teens while they are at the mall.

• Inform your children and community about the reality of trafficking It spans every race, gender and neighborhood in America—including yours.

• Have clear family rules such as: Under no circumstances are your children and teens to approach a stranger's vehicle; and your teens are to hang around age-appropriate friends.

• Request your teens give you their cell phone overnight.

SOURCE: courtneyshouse.org

Comments