Uninsured Americans who are hoping the new health insurance law will give them access to weight loss treatments are likely to be disappointed. Photo by Courtesy Flickr/Return the Sun

This KHN story was produced in collaboration with NPR.

JACKSON, Miss. — Uninsured Americans who are hoping the new health insurance law will give them access to weight loss treatments are likely to be disappointed. That's especially the case in the Deep South where obesity rates are some of the highest in the nation, and states will not require health plans sold on the new online insurance marketplaces to cover medical weight loss treatments, whether prescription drugs or bariatric surgery.

Dr. Erin Cummins directs the bariatric surgery department at Central Mississippi Medical Center in the state capital of Jackson. She grew up in the Delta, her husband is a cotton farmer, and although she's petite and fit, she understands well enough how Mississippians end up on her operating table.

"You have to realize in the South, everything revolves around food. Reunions, funerals, parties—everything revolves around food," Cummins says.

That long-standing culture—and other factors like inactivity and poverty—have saddled Mississippi with the highest obesity rate in the nation. Doctors here are no longer surprised to see 20-somethings with diabetes, hypertension, sleep apnea, heart disease and severe joint pain. And the prevalence of severe and super-obesity is growing rapidly. For those patients, bariatric surgery is considered the most effective treatment to induce significant weight loss.

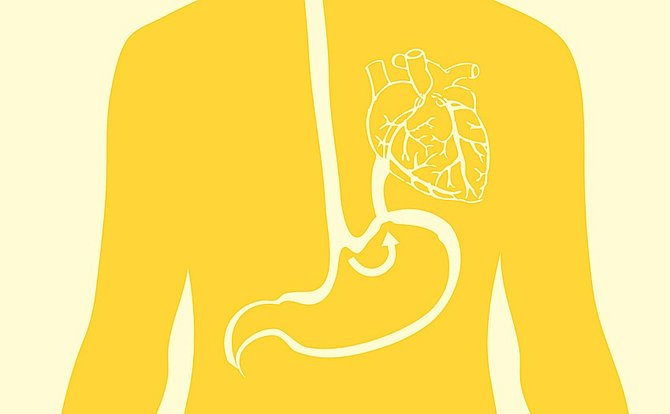

Cummins describes the procedure: "We're restricting the stomach size to where a patient isn't going to eat as much. Then we re-route the intestines a little bit and realign it to delay digestion, so to speak, to bypass it. So everything a patient eats in a gastric bypass is not going to be absorbed."

After surgery, many of the complications of obesity, like sleep apnea and high blood pressure, are reversed. Multiple studies have found that 80- to 85-percent of diabetics can stop medication in the first year.

Medicare and some two-thirds of large employers in the U.S. cover bariatric surgery. But the procedure is pricey—an average of $42,000—and many small employers, including those in Mississippi, don't cover it.

That economic fact is setting the course for the rollout of the Affordable Care Act.

Dr. John Morton is director of bariatric surgery at Stanford University and has led his surgical association's national and state lobbying efforts.

"Our hope was that there would be a single benefit for the entire country, and as part of that benefit there would be coverage for obesity treatment," says Morton.

But amid worries that a uniform set of benefits would be too expensive in some states and sensitive to the optics of the federal government laying down one rule for all states, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services changed course. It decided to have the benchmark plan—that sets the minimum level of benefits that must be covered—key off the most popular small group plan sold in each state, in essence reflecting local competitive forces.

That's led to an odd twist: In more than two dozen states, obesity treatments—including intensive weight loss counseling, drugs and surgery—won't have to be covered in plans sold on the exchanges.

Some of these states—Alabama, Louisiana, Arkansas, Texas and Mississippi—have the highest obesity rates in the nation, according to the Centers for Disease Control. Morton applauds the growing awareness around obesity prevention in the U.S., but, he says, some 15 million Americans who are already severely obese still need medical treatment.

"If they don't have insurance, they're not going to get the therapy," Morton says. "We see cancer therapy covered routinely. We see heart disease covered routinely. Why is it that we don't see obesity coverage routinely?"

Therese Hanna, Executive Director of the Center for Mississippi Health Policy, isn't surprised that obesity treatments are excluded in plans sold on the insurance exchange in her state. She says it all has to do with keeping cost down for many people who will be buying insurance for the first time.

"With the discussions around what should be covered under the exchange within the state, a lot of it had to do with balancing cost versus the coverage," says Hanna.

Hannah says Mississippians who buy insurance on the exchange will likely be the cashiers, cooks, cleaners and construction workers that make up much of the state's uninsured. And even though many of them will qualify for federal subsidies, the price of monthly premiums must be kept low.

"If you try to include everything, the cost would be so high that people wouldn't be able to afford the coverage, so you defeat the purpose," Hanna says. "And that's been most of the discussion in our state is how do we provide the kind of care for things like high blood pressure, diabetes and heart disease. So we have a lot of needs to be covered other than obesity itself."

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus