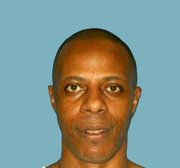

Willie Jerome Manning came within a hair of being put to death Tuesday evening.

Four hours before the Mississippi Department of Corrections was to carry out a Manning's death sentence for the 1992 murders of two people in Oktibbeha County the state Supreme Court granted a stay of execution. The stay remained effective as the Jackson Free Press went to press Tuesday evening.

Manning had been desperately trying to get key forensic evidence tested that he claimed would exonerate him, but the courts repeatedly rebuffed the efforts.

In the days leading up to Manning's execution date, however, the Federal Bureau of Investigation twice admitted that investigators overstated the scientific significance of evidence during Manning's original trial.

Prosecutors maintained that Manning sold several items that belonged to the victims and that bullets Manning used for target practice matched bullets recovered from the bodies of the victims, Jon Steckler and Tiffany Miller. On May 6, the FBI admitted: "The science regarding firearms examinations does not permit examiner testimony that a specific gun fired a specific bullet to the exclusion of all other guns in the world."

"The jury was not given all the information," said Benjamin Russell, executive director of Mississippians Educating for Smart Justice, a Jackson-based anti-death-penalty organization. "When you're dealing with the legal system, semantics can play a huge role."

That admission from the FBI follows a previous letter the agency sent to Oktibbeha County District Attorney Forrest Allgood, who prosecuted Manning, U.S. Justice Department officials state "that testimony containing erroneous statements regarding microscopic hair comparison analysis was used" in Manning's case.

At the time of Manning's trial, investigators found a hair in the victims' car that tests revealed belonged to "a person of the black race." However, as DNA testing technology has advanced in the past 20 years, Manning has asked the courts to retest biological material found at the crime scene.

As grue-some as the murders were, there should be lots of biological material to test. One of the victims, Tiffany Miller, was shot twice in the face at close range. One leg was out of her pants and underwear, and her shirt was pulled up. Her boyfriend John Steckler's body had abrasions that occurred before he died, and he was shot once in the back of the head. A set of car tracks had gone through the puddles of blood and over Steckler's body.

One of the issues Manning raised in his appeal is that Allgood illegally kept African Americans off Manning's jury by dismissing potential jurors who said they read African American magazines. David Voisin, Manning's attorney, said if approved, the testing could take several weeks, depending on which lab is used.

On May 3, at the Mississippi Capitol, death-penalty opponents and Manning supporters called on Gov. Phil Bryant to stop the execution. The Mississippi Innocence Project filed a brief in support of Manning this week.

Kennedy Brewer, who was exonerated in 2008 with DNA tests after being convicted and sentenced to death for killing his girlfriend's young daughter, also wrote Bryant asking to give Manning the same opportunity to clear his name that Kennedy received.

Sister Maati, of Our Community Against Racism, invoked this year's 50th anniversary of Medgar Evers' assassination.

"Mississippi, prove that institutional racism is no longer a part of your southern heritage, or admit that the execution of Willie Manning is yet another Mississippi lynching," Maati said.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus