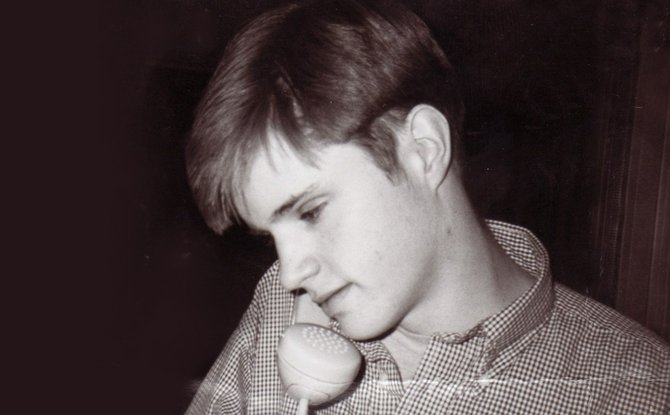

The murder of Matthew Shepard, a gay college student in Wyoming, led to the passage of federal hate-crime legislation as well as several books, film and plays, including “The Laramie Project.” A recent incident at a performance of “The Laramie Project” at Ole Miss reignited nationwide discussion of LGBTQ issues. Photo by Courtesy Judy Shepard/Matthew Shepard Foundation

On Oct. 12, 1998, Matthew Shepard, 21, asked a few guys at a local bar for a ride home. Instead of taking him there, they drove him into a rural area, tied him to a fence and beat him unconscious with the butt of a handgun. They then left Shepard hanging on the fence; he died six days later.

Aaron McKinney was one of the assailants, and his account of this event is immortalized in his confession to the Sheriff's Department of Albany County, Wyo. It was performed on stage earlier this month at Meek Auditorium at the University of Mississippi for a campus production of "The Laramie Project"—a documentary-style play that dramatizes real interviews of the Laramie community after the murder of Matthew Shepard, an openly gay man.

The effect wasn't quite what the cast of the production thought it would be at the Oct. 1 performance. After McKinney's character describes Shepard's appearance as a "queer" and "like a fag," audience members erupted in laughter and conversation, numb to caustic homophobic slurs of a murderer and to the fact that the actors on stage had to continue through their banter.

"I was really surprised that we were able to keep going," says Garrison Gibbons, 20, a BFA student of theater at Ole Miss.

The McKinney scene is arguably the most powerful moment in the play, occurring in the final act and portraying a feeling of careless apathy on the part of the killer. There's a sense of justification in what he's done that has homophobic roots, and he's far from remorseful even though he might be facing a potential death penalty or life sentence.

The cast remembers a growing arch of disruption during their Oct. 1 performance, one that began with an energetic audience and ended with an overwhelming sense of insecurity created by remarks made in the seats, including use of the word "fag" and jokes about a female character's weight.

"Overall, there were comments made at people's sexuality," says Gibbons, an openly gay cast member, "even comments made about someone's weight and race."

'Accosted and Insulted'

The pivotal moment came in the second act when one of the Laramie citizens represented in the play declares that he is a homosexual. The reaction, the cast says, was a shocking amount of laughter and heckling from a crowd made up mostly of Ole Miss students. Some audiences took pictures of cast members on their phones and directed homophobic slurs at the actors.

"I didn't expect my friends to be accosted and insulted on stage," says Adam Brooks, 22, a BFA student of theater at Ole Miss and a cast member. "I didn't expect people to take pictures of us. I didn't expect any sort of hate to be vocalized."

The cast members were shocked to see a play about human empathy become a stage for prejudice and belittlement.

"Once the incident happened, it was easy to draw parallels about what was happening on stage and the things that we're talking about right now," says Nathan Burke, 21, a musical theater major and cast member. "I don't think we were quite ready for that."

The Daily Mississippian, the student newspaper at Ole Miss, broke the story about the disruption two days later on Oct. 3, reporting that an estimated 20 football players attended the play, with some participating in the disturbance.

University administrators instructed Ole Miss' Bias Incident Response Team (BIRT) to investigate the reports discover who was involved. Chancellor Dan Jones and director of athletics Ross Bjork issued a joint apology on the university's behalf for the misconduct of the students that night.

"Incidents like this remind all educators that our job is to prepare our students to be leaders in life during their years on campus and after they graduate from Ole Miss," they wrote. "This behavior by some students reflects poorly on all of us, and it reinforces our commitment to teaching inclusivity and civility to young people who still have much to learn."

Rory Ledbetter, the director of "The Laramie Project" at Ole Miss and an assistant professor of voice and acting, wasn't sure what type of reactions the play would receive once it was produced.

"I knew it would tap into some deep-seated stuff in the community and student body," Ledbetter says. "But, I had no idea what happened that night was about to happen."

Darby Burghard, 19, another theater student in the play, describes how difficult it was to follow scenes in which the audience was unruly.

"I was really angry at the way things started to happen at the beginning of the play, but at the very end (after the McKinney scene) I just started to cry before I took the stage."

Though this play manifests as a response to a homosexual man's death, Ledbetter and the cast said the community members of Laramie are the focal point of the play, which examines how different individuals deal with their prejudices, limitations and changing beliefs. The play's themes revolve around human empathy and understanding, something that starts with gay rights but moves outward into a larger picture.

"Matthew isn't in the show," says Jade Genga, 21, a cast member and musical theater major. "He could be anyone, being discriminated against for anything. I think that was more the point."

Sense of Empowerment

Ledbetter acknowledges that the cast was very troubled initially by the Oct. 1 performance, but after an outpouring of both national and international support, Ledbetter witnessed a noticeable change in the performances.

"All of a sudden, there was a sense of empowerment in the cast where they felt the support of the greater community," Ledbetter said. "Thursday and onward, the performances were just electric."

Nathaniel Weathersby, the president of LGBTQ organization UM Pride Network and a senior at Ole Miss, was there for one of the performances that followed the incident. He noted that though the national spotlight may seem damaging, it could lead to more discussion about topics that are often left unattended.

"I do feel Mississippi and the university have a lot of work to do," Weathersby said, "but sometimes bad press can give the state motivation to move in the right direction."

That direction, for Weathersby, means moving toward a campus and community life where those who don't fit the heterosexual mold can live and express themselves openly, without interference or unnecessary attention.

"The rhetoric I use is that I'm not completely comfortable as a queer person on this campus," Weathersby said.

"I can exist here and go to school here, but I'm not as comfortable being here as my heterosexual counterparts."

Jennifer Stollman, the academic director at the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation, led a restorative-justice dialogue session a week after the play incident that was mandatory for all those who attended that night.

General responses from students were positive. The sessions addressed the common perceptions that lead people to disrespectful and often discriminatory, insensitivities. The idea of creating a more inclusive environment where matters of race and sexual orientation can be discussed without the need to voice discomfort was important to Stollman and those working to alleviate this situation.

"We had a significant amount of students come and most were interested and engaged," Stollman said. "I was impressed with their ability and willingness to share their thoughts and opinions."

Stollman's session was a small piece of the reconciliation efforts. She recognizes that issues of sexual orientation, race, and image are an ongoing discussion, and that it is important to expose new students to "different perspectives, experiences, and paradigms" they may encounter on a campus environment, an perhaps help prevent nights like Oct. 1 from happening again.

Matthew Shepard's mother, Judy Shepard, spent several years after her son's death touring the country and speaking about hate crimes. In an interview with the Daily Mississippian in 2005 when she visited Oxford, Shepard also encouraged the idea of ending the ignorance that spurs hate crimes.

"The reason that I travel the country is that I don't want this to happen anymore," said Shepard. "Matt is no longer with us because those that took his life learned how to hate and were given the impression that society condones their behavior."

Ledbetter said, ultimately, performers of "The Laramie Project" took part in a valuable transformation that allowed them to both see and participate in these issues on stage, operating between real-world discrimination and the story they were trying to tell.

"Before the event, I told them that they were performing 'The Laramie Project,'" Ledbetter said.

"After it happened, I told them that they were living 'The Laramie Project.'"