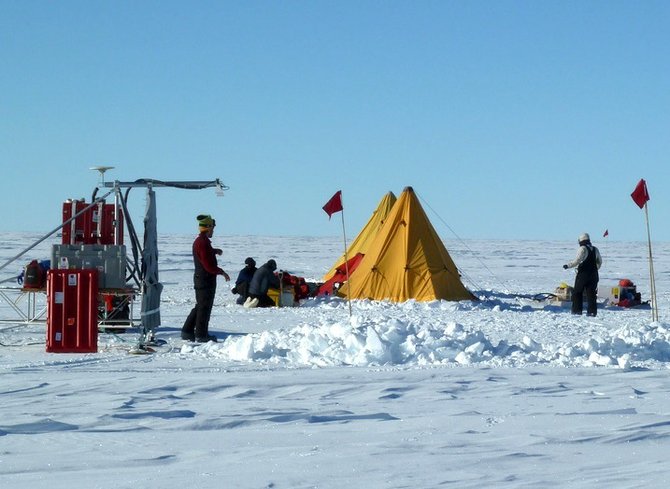

Researchers set up camp on a traverse of Antarctica to study snow accumulation on the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. The science of climate change may be more certain than ever, but the uncertainties continue to dominate the news. Photo by Courtesy Lora Koenig/NASA

The word early from scientists gathered in Stockholm is clear: The planet is changing, and humans are the cause.

But the message from media outlets in the days and weeks leading up to Friday's release of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change assessment presented a far murkier picture: Global temperatures haven't risen in the past 15 years, Arctic Sea ice is growing and scientists are scrambling to explain why.

Six years after the IPCC's massive Fourth Assessment Report was excoriated for a handful of errors, four years after the uproar over leaked emails put scientists on the defensive, the climate denial camp still controls the message.

"The framing of many media stories has been very disappointing," said Susan Joy Hassol, director of Climate Communication, a nonprofit science and outreach project dedicated to furthering scientific understanding. "The media is being distracted and misled by the denial machine."

The tactic is not new. Every election cycle candidates wage a PR war to get out in front, define the terms and win the debate before their opponents get started.

The Swift Boat campaign has become the classic example, having torpedoed John Kerry's 2004 presidential bid. Much of that early reporting came from the conservative Cybercast News Service and then-reporter Marc Morano, well known by scientists for later serving on Sen. Jim Inhofe's staff and for regularly skewering climate science today via his Drudge Report-like website, ClimateDepot.com.

Every six years or so, the IPCC reviews the robustness of climate science, summarizing the state of the knowledge for policymakers in a series of reports rolled out over several months.

The first report and summary was officially released Friday. Leaks and analyses have dominated the climate news for the past week, but many headlines have offered the public some variant of the following, from Der Spiegel: "Warming pause? Scientists confront an inconvenient truth."

Those in the business of playing to the denier base are in especially deep clover.

Others have noted that this September's Arctic Sea ice minimum has rebounded considerably from last year's record low. A half dozen have questioned whether the panel, created in 1988 to act as an interpreter for policymakers worldwide, remains relevant.

"The real take-home message is that the confidence has increased," said Hassol.

That's reflected in any number of findings in the report: Extreme weather, sea-level rise, ocean heat.

But that message has been buried.

"Instead of focusing on all of those things, people are overly focused on the short-term slowing in the rate of increase of one variable - surface air temperature," Hassol said.

Those in the business of playing to the denier base are in especially deep clover, with conservative talk radio reporting the IPCC has "officially conceded" no global warming since 1998 and Bjorn Lomborg, director of the Copenhagen Consensus Center, writing about "global warming without fear."

But for Hassol, the media are to blame for being distracted, and the scientists are outgunned.

"Scientists focus on the science. The deniers act more like lawyers," she said. "The media battle between the climate scientists and the denial machine is like a fight between the Boy Scouts and the Marines."

The fight will never be symmetrical, cautioned Andrew Revkin, editor of the Dot Earth blog, who wrote a 2010 article exploring what would happen if the public had "perfect" climate information.

There will always be uncertainties and caveats in the science, he said, and those uncertainties will always be easily exploitable.

"There's been a false perception, propagated by the climate activism community, that if they just get the message straight, that somehow the world and country would decarbonize, just on the evidence."

The reality is that we love fossil fuels, he added. "Everything we do, for the moment, is based on coal and oil.... Anyone who wants to maintain the status quo has a very easy job."

"This IPCC report and the next one and the last one are not going to change" those underlying fundamentals, Revkin said.

Still, climate scientists and the climate advocacy camp have had years to prepare for Friday's unveiling—and the expected barbs. Efforts have come and gone to inform journalists, shape the debate, and correct errors and call out distortions.

Veteran UK campaigner Joss Garman, founder of Plane Stupid, sounded the alarm three years ago as well, in an opinion piece published by The Guardian.

"At the moment," he wrote in that 2010 essay, "there's a real danger that when the next major IPCC climate assessment report is released, the likes of the BBC will feel the need to spend 30 percent of their coverage remembering an inconsequential error about Himalayan glaciers in the last report, because the battle here is over trust and perception."

Yet somehow other groups have successfully put industry on its heels: A college professor, Bill McKibben, has almost single-handedly turned Canada's tar sands into a political hot potato globally with his focus on the Keystone XL pipeline. Tribes and Northwest activists have hemmed Powder River Basin coal exports.

To be fair, some media have focused on the long-term trends: The Associated Press' Seth Borenstein explored what 95 percent certainty means to scientists. And National Geographic asked whether the focus on the "warming pause" missed the big picture.

But little coverage has linked extreme—and fatal—floods in Colorado, Mexico and Asia to more robust findings within the IPCC report. Or latched on to more assertive predictions about sea-level rise, a major blind spot in the science six years ago.

The denial camp has again won the PR battle here. Whether climate advocates and scientists can wrest back the debate as the IPCC rolls out the rest of its Fifth Assessment over the next few months is as much a question today as it was in 2010.