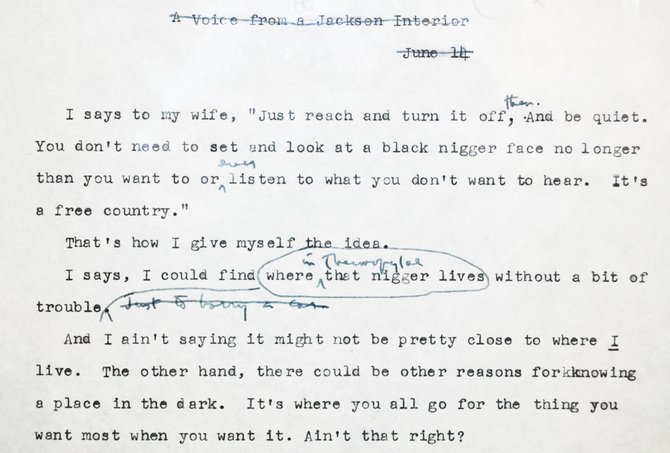

“Life Into Fiction: The Murder of Medgar Evers and ‘Where Is the Voice Coming From?’” showcases Welty’s writing process. Photo by Trip Burns.

Eudora Welty only wrote one story in anger. She drafted it the day she learned of Medgar Evers' assassination.

"Where is the Voice Coming From?" appeared in The New Yorker magazine about a month later, in July 1963. When she wrote it, Welty didn't know the name of Evers' killer. The city of Jackson became Thermopylae, the Grecian gate to Hades.

Welty did know bigoted Mississippi whites of the era, 100 years after the end of slavery. She delved deeply into that "alien and repugnant" mindset and wrote her fictional account from the assassin's point of view.

"Whoever the murderer is, I know him: not his identity, but his coming about, in this time and place," Welty wrote later. "... I felt, through my shock and revolt, I could make no mistake."

Welty's story proved prescient. In one passage, the killer watches after firing the fatal shot:

"Something darker than him, like the wings of a bird, spread on his back and pulled him down. He climbed up once, like a man under bad claws, and like just blood could weigh a ton he walked with it on his back to better light. Didn't get no further than his door. And fell to stay."

A Eudora Welty House exhibit focuses on the story. Evers and his wife, Myrlie, were leaders in the Civil Rights Movement; Medgar Evers was Mississippi's first NAACP field secretary.

The exhibit features photos and brief bios of Evers and his killer, Byron de la Beckwith, along with a film container from a white Citizens Council forum and campaign buttons for Ross Barnett, whom the assassin mentions in Welty's story.

Barnett, governor from 1960 to 1964, was an avowed segregationist who repeatedly defied efforts to end Jim Crow racial discrimination in Mississippi. Famously, he interrupted the testimony of Evers' widow, Myrlie Evers, at de la Beckwith's second trial for murder to shake the killer's hand. Two all-white juries failed to reach verdicts in 1964. A third trial in 1994 finally secured de la Beckwith's conviction.

Welty eerily captured the machinations of a murderer's mind. Quotes from "Where is the Voice Coming From?" caption crime-scene photos from the assassination site at the exhibit.

The centerpiece, however, is Welty's original draft of the story. The author's crabbed notes appear between the lines and in the margins of the yellowing paper. She rewrote the title several times and included her editor's comments. He asked Welty to eliminate details that might prejudice a jury.

While Welty did not join marches, her quiet determination made an indelible impact on readers. "She felt very strongly that her fiction was her activism, although she didn't quite say it that way," says Bridget Edwards, director of the Eudora Welty House and curator of the exhibit. "That was her contribution."

Welty also took part in Social Science Forums at Tougaloo College and spoke widely in other settings. In 1963, segregation was the rule in Mississippi schools, but Welty advocated for open admission to her literary festival keynote speech at Millsaps College, for example, and the administration acquiesced.

For writers, Welty's meticulous process is a revelation. To restructure her work, she cut the paragraphs apart and used sewing pins to tack the strips to clean paper, rearranging and rewriting until she was satisfied. Today, when word processors can obliterate writer's drafts, Welty's award-winning example sets a high standard for the writer's craft.

See "Life Into Fiction: The Murder of Medgar Evers and 'Where Is the Voice Coming From?'" through Feb. 13 at the Eudora Welty House Education and Visitors Center (1109 Pinehurst St.). Visit eudorawelty.org or calll 601-354-5219 for more info.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.