In May 1964, United Klans of America Imperial Wizard Robert Shelton wooed hundreds of Pike County citizens into choosing his Klan organization over that of Sam Bowers of Laurel. The UKA terrorized the county, earning it the moniker “Bombing Capital of the World.”

"If you belong to the Ku Klux Klan

Here's my heart and here's my hand,

If you belong to the Ku Klux Klan

We are marching for a home ..."

(from a Klan leaflet distributed in 1964)

There were no Klan robes in sight the night the violent Wolf Pack was born in southwest Mississippi.

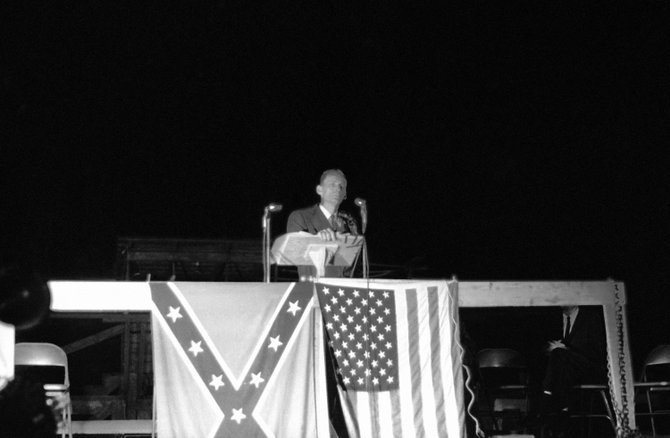

It was Sunday, May 17, 1964, when McComb Selectman Phillip Brady crawled up on the trailer bed at the Pike County fairgrounds on Wardlaw Road, roughly a mile south of McComb's all-black Baertown district. Thousands were expected that night.

The makeshift stage—a flatbed trailer delivered from Herbert Lamb's lumber mill by my grandfather—held a podium draped with both American and Confederate flags. While Oscar Ray was no Klansman, he did as Mr. Lamb ordered.

Selectman Brady was the second-in-command to Mayor Gordon Burt, the virulently racist East McComb businessman and head of the local Citizens Council, formed in the southern states after the U.S. Supreme Court demanded integration in its 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. Brady was there to incite the crowd of nearly 1,000 white people gathered to oppose what their local newspaper editor Oliver Emmerich had called the "threat of invasion" of college-aged COFO workers. For weeks, whites across the county had been reading unrestrained newspaper articles describing how these civil-rights activists were preparing to descend on Mississippi within weeks to register African Americans to vote.

Phillip Brady had served honorably with the Navy in the South Pacific. When Brady returned to McComb during the mid-1940s, Lit Alford, a local oilman and business owner, helped him establish the WAPF radio station within the downtown Pike Hotel on Front Street. Using his airwaves as an influential tool for the segregationist cause, and his control over the police force through his elected position, Brady would forge an infamous legacy for himself over the summer of 1964.

Brady was already well-known throughout the white community as the head of the First Baptist Church's "n*gger committee." This assemblage of outspoken Christian gentlemen would wait in the church's vestibule to intercept and block African Americans who tried to enter.

As Brady greeted the anxious crowd of white faces on that Sunday night in May, he made sure to mention how regrettable it was that the mayor was out of town and unable to personally welcome such a distinguished guest as the leader of the Alabama Ku Klux Klan. He then introduced United Klans of America Imperial Wizard Robert Shelton, a Tuscaloosa, Ala., hate monger intent on usurping Klan territory in Mississippi.

'Under the Heels of Tyranny'

Imperial Wizard Shelton was a clean-cut, wiry man who had tried unsuccessfully to blow up Martin Luther King Jr.'s Birmingham hotel room roughly one year earlier. He was dressed in a dark suit, and spoke spiritedly from atop the trailer bed at one end of the horse-show arena, warning his enthralled audience about the threats that both Negroes and Communists posed to their community.

"(The South) is once again under the heels of tyranny!" Shelton proclaimed.

A charismatic orator, Shelton warned that the Communists were using the black people of Mississippi as pawns in their master plan of subversion. "If Negro leaders and white liberals are so interested in building up the Negro race, why can't they use this money to bring the moral standards of the Negro up to our level where they might be better accepted?" Shelton asked.

The Klan leader reminded the seething crowd of what northerners had done after winning the Civil War and ending slavery, a time before Jim Crow laws when blacks in Mississippi briefly held statewide office.

"The Communists set out in 1925 to ruin the purity of the American race by concentrated use of the misinformed and misguided Negro race," Shelton stated. "Another Reconstruction is taking place."

Shelton then turned his attention to Curtis Bryant, the black Illinois Central crane operator and NAACP leader who first invited Robert P. Moses to establish a voter-registration program in McComb and Pike County back in 1961. Moses had been a favorite target of area racists three years earlier, and was helping organize the upcoming invasion, officially named "Mississippi Freedom Summer." Klan night riders had bombed Bryant's Baertown barbershop less than three weeks before the Klan rally.

"Has anyone asked the postmaster if the Negro whose barbershop was bombed here recently has had a tremendous increase in mail? It is probable that the local Negro 'bombing victim' has received as much as $50,000 to $60,000 in money through the mails since the incident," Shelton sneered.

Joining Shelton and Brady on the stage to welcome the UKA's newest battalion of Christian soldiers—a motley group that would infamously become known as the "Wolf Pack"—were retired local tailor Ernest Jackson, Rev. Winfred Lowery of the Johnston Station Baptist Church and Rev. J.C. Brown of Brookhaven's Marinatha Baptist Church, the Enterprise-Journal reported.

Seeing Red, Fearing Black

It is fascinating to consider the profound psychological effect that the Communist threat had on Shelton's audience. Most Mississippians did not know a single Red, and the days of the 1930s, when the American Communist Party had boasted a couple hundred thousand members, had long since passed. By this point, fewer than 10,000 remained nationwide, but to the emotional minds of these simple, woodland people, such statistics were of little consequence.

Shelton's incendiary words, thus, struck a chord with the men gathered at the fairgrounds that night.

McComb oilman Emmett Thornhill, an illiterate millionaire who had fanned the segregationist flames for many years, gloated to the Associated Press the next day about the rally's success. Drunk on his own propaganda, Thornhill claimed that the Klan currently had "a third of the votes in Mississippi," bragging that current membership logs contained the names of over 96,000 individuals statewide and more than 3,000 Pike Countians. "Hell, we might even hold a statewide rally near Jackson this summer," he added triumphantly.

When questioned about the assembly on Wardlaw Road, Thornhill stated: "We left it open for the public. We don't want folks to think we're going out to beat up some poor old Negroes. We're not against the Negroes, we're against the Communists."

Asked about law enforcement, Thornhill added: "They haven't bothered us. Besides, a lot of them are members, anyway." Indeed, the rally enjoyed an impressive turnout of state patrolmen, county deputies, and city police officers.

Thornhill also defended the mass cross burnings at varying Pike County locales throughout the preceding months, including in front of the home of "moderate" Enterprise-Journal Editor Oliver Emmerich. They were intended "to lighten people up that's in the dark," he said.

Thornhill, though, must have been disappointed in the turnout for Shelton. He had bought radio and newspaper advertisements to promote the event and had boldly predicted in Emmerich's Enterprise-Journal that between 15,000 and 20,000 persons would come to hear Shelton speak.

Still, with its 1,000 participants, it was the largest Klan rally in the county's history.

With Christian Reverence

In U.S. history, the Ku Klux Klan—which W.J. Cash called "the sentimental cult of the Confederate soldier" in his 1941 classic "Mind of the South"— has reared its ugly head in dramatic fashion three times, including its creation after the Civil War to scare newly freed slaves away from the ballot box.

The Klan's level of prestige peaked in the 1920s, when 5 million Klansmen represented nearly 20 percent of the American voting population—especially after D.W. Griffith's silent film "The Birth of a Nation" romanticized the Klan in 1915. New Klansmen used the film as a recruiting tool as they rebirthed the group in Stone Mountain, Ga., the same year.

In the 1960s, thousands of men in Mississippi would rally once more for a final clash with the Yankees, one last battle against the American thesis. This glorious struggle would be their Thermopylae.

Until Robert Shelton and the UKA came to Pike County that Sunday, a Mississippi-based Klan organization run by Sam Bowers of Laurel, the White Knights, was dominating anti-black terrorism in south Mississippi. By February 1964, Sam Bowers—a 40-year-old career bachelor, World War II veteran and the owner of a vending-machine company in Laurel—had wrested control of the White Knights away from founder Douglas Byrd.

In Bowers' opinion, the Klansmen of Mississippi were far too passive in early 1964 to properly battle the coming civil-rights invasion. Together with Grand Dragon Julius Harper, the Klan Bureau of Investigation Director Ernest Gilbert, and a sociopathic preacher from Neshoba County named Edgar Ray Killen, Bowers began opening scores of Klaverns throughout the Pine Belt.

Bowers made it clear that the White Knights' mission was not just to torment the northern agitators, but to assassinate COFO's leaders. The imperial wizard accumulated more than 5,000 followers in only a few months for his "holy crusade," telling recruits they would need "a solemn, determined Spirit of Christian Reverence." If they were ordered to kill someone, "it should be done with no malice, in complete silence, and in the manner of a Christian act."

On Feb. 15, 1964, Bowers called a secret conclave near Brookhaven, a town 20 miles north of McComb, directing 200 of his new followers into the deepest woods of Lincoln County with the help of Coca-Cola cartons left along the route like breadcrumbs.

Bowers made sure that security was hermetic that night. Men patrolled the perimeter, some on horseback, staying in constant communication on walkie-talkies. Along the margin where field met forest, more Klansmen were stationed with .45 automatics clearly visible on their hips. From time to time, some stepped casually to the tree line and enjoyed a swig of the winter-chilled moonshine hidden in the bushes.

Anxiously awaiting Bowers, most of the Klansmen gathered in tightly like a sinister waddle of Emperor penguins around a flatbed trailer. After the Klan Kludd (spiritual adviser) delivered the benediction, the star of the show took center stage.

"Fellow Klansmen, you know why we are here," Bowers shouted. "We are here to discuss what we are going to do about COFO's n*gger-communist invasion of Mississippi which will begin in a few months." He told the naive rednecks how a "pincer movement of agitation," comprised of federal troops and Communist indoctrination, would soon threaten their southern traditions.

In the frigid air, Bowers' voice floated on clouds of steam: "If this martial law is imposed, our homes and our lives and our arms will pass under the complete control of the enemy, and he will have won his victory."

The group's path toward infamy began that night, as Bowers announced the return of the night rides.

It was Stone Mountain all over again.

Bowers' tentacles soon spread into all facets of Klan activities in southwest Mississippi. After the meeting, Klaverns appeared all across the Pearl River region, and Klansmen from Meadville and Natchez committed several murders over the next several months as Freedom Summer unfolded, including the murders of Charles Moore and Henry Dee. Bowers' Meridian chapter soon found itself carrying out the iconic Philadelphia murders on Father's Day, 1964.

The White Knights' influence on Pike County would have been similar, but a few wealthy McComb patrons, including Emmett Thornhill and Phillip Brady, helped Robert Shelton and the UKA easily win over the locals. Still, while the UKA dominated Pike County, neighboring counties remained loyal to Bowers and the White Knights.

A Klavern BOOM

In the days following Shelton's speech, virtually every White Knight in the county abandoned Sam Bowers' organization to join the UKA, and eight new Klaverns were formed. Local men, including Ray Smith, J.M. Foster, John Brumfield, H.H. Mathews and J.R. Morgan, assumed the roles of chapter presidents, or Exalted Cyclops.

By far, the most militant of these Klaverns belonged to Ray Smith—an East McComb resident and a local executive for Southern Bell. To his neighbors, Smith was a pleasant guy, and even served as a deacon at the East McComb Baptist Church. One of his brothers was the fire chief, and his brother "Goose" worked for the gas company.

Ray was candid and passionate about his beliefs. After all, to be an Exalted Cyclops, and to lead the salivating members of the night brigade, one truly needed to be a scoundrel of the highest order. With large monetary contributions collected from Emmett Thornhill, Ed Wilkins, Gene Deer and C.C. Warner, the proud anarchists of Klavern #700 dug in, their broadswords gleaming, and prepared for the Communist-inspired blitzkrieg.

Local Klansmen believed that to embrace integration, and the coming invasion of college activists, was to accept everything about Yankeedom that they found so revolting. If the spear of segregation needed a point, the guerillas of Pike County were more than willing to prove it. Unspeakable acts of brutality could happen in these woods—just as they had in the past—while remaining free from the national publicity provided by all those pesky news cameras. After all, there simply were not enough federal bayonets to guard every isolated church and family dwelling scattered across this immense forest.

Since the winter months, Klan night riders had marched and burned through the state at will. Dozens of cross-burnings had flared in the Pike County area alone in the first half of 1964, and within days of Shelton's McComb rally, more than 60 of Mississippi's 82 counties reported seeing these fiery displays. As the crosses proved ineffective against the more determined Burglund and Baertown activists, hooded bombers, members of the Wolf Pack, began to target black churches, homes and businesses.

In the minds of the quasi-crusaders, as long as the outcome benefitted the white establishment, even the most disgusting means became acceptable and heroic.

'In Treasure and Blood'

Across the state, the irresponsibility of the state's newspaper editors was astounding in those pre-Freedom Summer days as they wrapped Mississippians in the purest demagoguery and stripped them naked in the face of terror. Voter registration would spell the doom of their cotton-patch Camelot. This new threat, this inevitable invasion, was, as W.J. Cash phrased it, "a challenge to (the southerner's) universal illusion of being the chosen son of heaven, and so an intolerable affront to his ego, to be put down at any cost in treasure and blood."

Throughout May, unrestrained headlines, like "Mississippi Armed for Summer" and "Planned Invasion in Mississippi," ran across the front pages of McComb's Enterprise-Journal. The paper told readers that state officials had armed themselves with "new laws and techniques to combat an expected influx of civil rights workers," but all the average McComb resident heard was "invasion." The volatile personality of the southern frontiersman was ready to show its teeth. They didn't need the state; local captains had the situation well in hand.

During the last week of May, Emmerich and most every other editor in Mississippi officially dubbed the upcoming summer an "invasion." In McComb, people were already panicked about a Communist takeover, so the Enterprise-Journal's newest article only bolstered the unrest. Nervous frontiersmen stood at a defining moment for their Anglo-Saxon culture, and were ready to meet the small contingent of college students—akin to the medieval Children's Crusade—with all the fervor they could muster.

Emmerich's front-page editorials outlined community preparations for the "invasion" while pleading with McComb citizens to act responsibly. He warned his readers on May 29: "Our conclusion is that we should all try to relax. May we, on September 1, look back on the summer of 1964 and be able to truthfully say, 'We met a crisis with maturity. We did not panic. We exercised restraint. We upheld the dignity of the law. We met a challenge intelligently."

Such restraint was not to be.

'I'll Shoot You In Two'

June 1964 was quickly shaping up to be a volatile month, both in Mississippi and with vitriolic civil-rights debate in the U.S. Congress. The U.S. Senate was nearing completion of 10 weeks of long-winded filibusters coming from the Dixiecrat contingent. It might have been the moment these demagogues, the supreme masters of the stump, had been groomed for all their lives.

Republicans and non-Southern Democrats were tantalizingly close to getting the votes necessary to invoke cloture to halt the filibusters. With the magic number of senators growing nearer, the broadsword clansmen of Mississippi became even more desperate and impetuous. Their worst nightmare was coming true. Segregation would soon be outlawed.

The passage of civil-rights legislation was guaranteed only a few days later when 71 senators collectively ended the filibuster. White people in Pike County were beyond hysterical.

As June slowly drudged along, a 54-year-old black railroad worker named Ivey Gutter arrived at his Burglund home around 4:30 in the afternoon. Gutter worked for the Illinois Central for almost 20 years, and due to this seniority, he made slightly more money than the younger white men who shared the railroad yard. A great many of his co-workers were young, impulsive Klansmen who, utterly dissatisfied with Gutter's higher wages and membership in the NAACP, decided to remind him of his second-class position in McComb society.

As Ivey walked up the path to his home on June 11, 1964, he met a pugnacious, hooded quartet armed with pistols and shotguns. In broad daylight, they beat him unconscious with metal clubs before abducting him. When Gutter came to, he found himself lying across the back seat of a Klansman's car with one man sitting on his legs and another astride his shoulders.

The Klansmen drove him to a secluded spot outside of town, and then hounded the aging activist mercilessly about his NAACP affiliation. Occasionally, he was punched in the stomach or the face. The terrified black man tried to glance over his shoulder at one point, but was quickly warned, "Don't you look back, or I'll shoot you in two!"

After extracting whatever information they could, the men told Gutter to start walking. The kidnappers drove away, leaving him stranded several miles from home. Luckily, a friend of Gutter's lived not too far away, but when the bewildered railroad worker tried to call his wife, he found that his home's phone line had been cut.

That evening, Dr. Tom Mayer X-rayed Ivey at the local infirmary and gave him eight stitches to the scalp. While at the doctor's office, Sheriff Warren interviewed Gutter, who disclosed that the abductors' car was a 1954 two-door Chevrolet with a black top and a white bottom. He also disclosed that other occupants of the vehicle had called the driver "Charles" several times, and it had been "Charles" who headed the inquisition. Despite those clues, Sheriff Warren never pursued an investigation into the matter.

'I Couldn't See Them'

One week after the attack of Ivey Gutter, and days before Freedom Summer kicked off, a black mechanic named Wilbert Lewis was at work on Pearl River Avenue when an unknown man came into Matthews' Motor Company complaining of a leaking gas bowl. The fellow's car was just "down the street," he said, claiming to be in a real pinch. At about 4:45 p.m. on June 18, Lewis' boss, Howard H. Matthews (a local Exalted Cyclops) told him "to get a pair of pliers and a screwdriver," and to accompany the customer to where the car had allegedly broken down.

The unknown man drove Lewis a mile or two out Berthadale Road, in south McComb, before they came to the vehicle parked with the hood propped open. As he approached the vehicle, another man was stooped over the engine, so Lewis asked him what the problem seemed to be. For a moment, there was no response.

As Wilbert began to speak again, the stooped-over individual suddenly produced a pistol, and placed it forcefully to the side of Lewis' head. The frightened mechanic stood motionless, staring at the ground, not able to see their faces. The gunman ordered Wilbert into the back of the car, onto the floorboard, and then two additional men came out of the nearby bushes, wearing black hoods. They placed a canvass bag over his head.

The captors drove Wilbert around for almost half an hour until they reached an isolated, wooded area near the one-time county seat of Holmesville. They forcibly removed him from the car, assaulted him and forced him at gunpoint to disrobe. They then removed the sack from his head and bound him with chains to a tree.

As one man held a pistol to his temple, the other kidnappers grilled Lewis about numerous NAACP members and meeting places. The Klansmen wanted to know if rumors of an upcoming COFO civil-rights project in Pike County were true and where these reviled intruders would be housed.

When they found an answer unacceptable, the terrorists took turns striking him with a three-foot leather strap converted into a "cat-o-nine-tails"—a multi-tailed whip used for severe punishment. The first lash caused the victim to scream in agony. "If you yell again, your brains will be left on the side of the tree," one of the men responded.

The "cat" struck Wilbert more than 50 times, with many lashes leaving severe whelps along his back and the backs of his legs. After the beating, the men placed a noose around his neck, and for several moments tossed about the notion of lynching him, but decided not to.

"Can you run?" one man asked Lewis.

"Yessir," he responded.

"Tell Reverend Dickey to be damn careful about being round Liberty and Amite County," one of them warned. Dickey was a local minister and Lewis' father-in-law.

When Lewis reached down to pull up his pants, they struck him a few more times. He started running down a dirt trail, and after covering what he believed to be about a mile, found a creek where the path suddenly ended. Lewis left the worn thoroughfare, forded the river, and traversed through the forest until a proper road appeared. As he stumbled onto the gravel, a local black man spotted the bewildered mechanic and offered him a ride back to McComb.

In an unusual move for a Mississippi newspaper then, the Enterprise-Journal reported Wilbert's full account of the kidnapping and torture the next day on the front page. Within his report to the FBI, Lewis described the car that had picked him up at the motor company as a 1960 "blue-green" Chevrolet, and the car that was used to drive him to the woods of Holmesville as a 1950 "dirty green" Plymouth. Lewis was not sure, but he believed he could identify the man who came to Matthews' Motor Company, telling agents that "the man was 28 to 30, weighed 175 to 180 and smoked Lucky Strike cigarettes."

This report was forwarded to the U.S. Justice Department, along with information about a beating of three visiting New York journalists a couple weeks earlier. In response, swarms of federal agents came to McComb to investigate. Tips were coming in already of other local blacks being beaten in similar fashion the same month.

'There Are Significant Risks'

By mid-June 1964, as the Wolf Pack continued its terror campaign to crush out civil-rights activity, all speculation had ended about whether or not COFO's "Freedom Summer" would actually materialize. Newspapers and conservative editors across Mississippi ominously warned of students gathering at a sycamore-shaded women's college in Oxford, Ohio, to make preparations for "a summer in Mississippi." Droves of activists were arriving there by Volkswagen, beat-up old Fords, motorcycles and Greyhound buses. Reality began to set in as emotional Pike Countians now knew the invasion would officially commence within a week or two.

The young people in Ohio, predominantly Ivy League undergraduates from Cornell, Princeton, Harvard and Stanford universities, received a crash course in civil-rights activism, including how to engage in non-violence when under attack. There, Freedom Summer organizer Bob Moses warned an auditorium filled with these trailblazers of racial tolerance: "Don't go into Mississippi with your eyes closed. You must understand that there are significant risks."

Among the roughly 200 young men and women training in Ohio that June was a 20-year-old New York Jew named Andrew Goodman. When he had left the University of Wisconsin to travel to Ohio, this unassuming student had no idea that he would soon become a part of the Hospitality State's most infamous civil-rights slaying on the first official day of Mississippi Freedom Summer.

That day, June 21, 1964, Bowers' White Knights abducted and executed Goodman, along with two other COFO workers, white New Yorker Michael Schwerner and black Mississippian James Cheney, on the lonely Rock Cut Road south of Philadelphia in Neshoba County. Their bodies, and thus proof of their murder, were not found until Aug. 4, and then thanks to a Klan informant.

For the six weeks that the bodies of Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner lay under a dam in Neshoba County, fellow COFO activists frantically searched for them, joined by national media and federal agents, even as white Mississippians—and the Neshoba Democrat newspaper—claimed that their disappearance was a "hoax" planned by civil-rights organizers, while others justified that they "came down here looking for trouble."

Meanwhile, a wave of Klan violence continued in Pike County that didn't attract nearly as much attention as the abduction of the three young men.

Bombs Away

Just one night removed from the disgraceful murders of the three civil rights activists in Neshoba County, a black schoolteacher from Baton Rouge, La., was sleeping in the front bedroom of activist Freddie Bates' Summit Street home in McComb. She was awakened by the sound of a car braking and crept to the window after hearing two car doors shut. Peering through the blinds, the boarder was horrified to see two white men lighting the fuses on multiple sticks of dynamite.

As the vigilantes prepared to make an example of Bates on June 22, the woman hastily retreated toward the back of the house, screaming wildly along the way. Bates and another boarder awoke just in time to hear a massive explosion, then crashing glass. The bomb blew off the front porch of the house, and boards fell from the ceiling.

Two more explosions rocked homes in the black communities of Burglund and Baertown that night. Around 10 p.m., and only a few blocks away from the first explosion, Corine Andrews' home was bombed. Andrews worked as a cook for local white drugstore tycoon Norman Gillis Sr., and according to Charles Gordon in the Enterprise-Journal, she "(had) no known connection with civil rights cases and several persons speculated her home may have been dynamited by mistake."

In addition, local black activist C.C. Bryant's home was bombed on June 22.

'Off the Front Page'

As the Wolf Pack's bombings, beatings and harassment continued and increased that June, white residents became steadily more irritated with the constant stream of negative front-page news in the Enterprise-Journal. From their languid perspective, the violent campaign against Burglund residents was not affecting them directly, so why should they be forced to read about it? Many readers felt that the stories of bombings and barbarism—including an extensive, firsthand account of Wilbert Lewis' abduction and beating—reflected poorly on the community, and they did.

However, it was an accurate reflection.

Managing Editor Charles Dunagin responded to these criticisms in the Enterprise-Journal on June 25: "It is the incidents themselves that cause the image and not the news reports so long as the reports are accurate and objective. Just because something goes unreported doesn't mean it hasn't happened."

Dunagin—who led the paper for 20 years after Emmerich's death in 1978—boldly challenged accepted local customs by stating, "If some of the things which are reported don't look so good to the community, then its citizens should think about correcting what is wrong rather than wishing that the news could be suppressed."

A bomb threat was called into the newspaper office the next day. On the night of the 27th, Klansmen hurled a bottle at Dunagin's home on Westview Circle in McComb. They intended for the bottle to penetrate a front window, but it hit a screen before bouncing onto the lawn. A note, created by a stamping device, was found in an envelope tied to the bottle of kerosene. It stated the following to the free-thinking, liberal reporter:

"Dunagin Keep anti civil rights action off the front page or move. Work with us, or against us and take the hard way. Take heed. KKK"

The editor's reaction was not the one Klan leaders had anticipated. Though not born in Pike County, the Hattiesburg native shared their frontier zeal. He removed a loaded shotgun from the hall closet, and then let it be known throughout McComb that he was willing to use it. With communal anxiety escalating, Emmerich summoned the big man himself, Emmett Thornhill, to the newspaper office for a conference.

Thornhill sauntered in off the street reeking of Kent cigarettes, his distended belly hanging over a gleaming silver belt buckle. The magnitude of the moment could clearly be seen on his stern, weather-beaten face. He removed his wide-brimmed hat, and asked to speak with Emmerich and Dunagin.

Behind the closed doors of Emmerich's office, Dunagin warned the Klan sugar daddy that if anything were to happen to his family, it would be Thornhill who would be looking over his shoulder. Such a move took courage, and though the Pike County bombing campaign continued terrorizing black residents and their white supporters through the summer—leading to McComb's moniker as the "Bombing Capital of the World" for a time—the Dunagin house would not be targeted again.

Opening the Closed Society

On June 29, 1964, the Mississippi Municipal Association hurriedly adopted a resolution requiring incoming civil-rights activists to register with local police departments upon their arrivals in various towns. Allegedly, this was a protective measure to ensure that no harm would come to the young people, but the safety of a bunch of Yankee meddlers was the last thing on the mind of the white establishment.

As June gave way to July, an Enterprise-Journal article announced—to the relief of white McComb—that members of COFO would not descend upon Pike County as early as expected. For the moment, Bob Moses and other Freedom Summer leadership had decided that the area was still too intransigent, and therefore refrained from sending any of COFO's limited volunteers there.

It had been three agonizing years since Moses had founded the state's first voter-registration school in Burglund, and during that time, the Camellia City had safeguarded both the ballot box and the sacred institution of segregation. In order to finally open the closed society of Mississippi, its most closed community would have to be liberated. Accordingly, the postponement would only be a temporary measure, and the return of mass civil unrest was now firmly guaranteed.

Within days of COFO's announcement, Moses stood before Mississippi's civil-rights advisory committee describing five racial killings recently committed in the southwest corner of the state and asserting that Natchez Klansmen were currently "funneling" firearms into the hands of their Pike County brothers. Moses also warned that members of local Klaverns were alleged to be "heavily armed with automatic weapons and hand grenades."

At the same time, impending civil-rights legislation remained an ominous threat, and the already desperate white men of Pike County grew more defensive.

On July 2, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the public accommodations phase of the Civil Rights Act. The new law banned major forms of discrimination against minorities, including "the unequal application of voter registration requirements and racial segregation in public schools, at the workplace and by facilities that serve the general public."

Among the state's many segregationists, this sickening moment rivaled, if not exceeded, the tragedy of that blackest of Mondays in 1954.

Gov. Paul Johnson—who had called the NAACP "n*ggers, alligators, apes, coons, and possums"— publicly prognosticated "some real trouble" when blacks attempted to desegregate Mississippi's public facilities.

State leaders advised restaurant and hotel owners to defy the new laws until they had been tested first in the courts.

In response, McComb's Norman Gillis Sr. turned his drugstore into a "private club," and most other local merchants followed suit.

Dynamite and Shotguns

With paranoia and discord already high among the unsettled white community, McComb finally received news in early July that the delayed arrival of COFO volunteers was over, and their unwanted guests would be there in days.

In reaction to the announcement, many frontiersmen—some of whom were already members of one or more of the local Klaverns—found additional solace in the newly re-established Pike County branch of the Americans for the Preservation of the White Race, or APWR.

Facing the amplified rhetoric of the COFO invasion, the necessity for the organization had returned, and Arsene Dick, an electrical contractor in Summit, was elected chapter president. He claimed adamantly that APWR was "in no way associated with the Ku Klux Klan," but basically, the two were mirror images.

Dick had fought during World War II to preserve his vision of America, and had come to "deeper religious convictions" after his military service. To him, the Lord was essential to the work of this organization, and he bluntly stated during a newspaper interview, "They took God Almighty out of everything, and that's our trouble today."

Of singular importance to the APWR was the need to "encourage" the funneling of money exclusively into the hands of white business owners. The manipulative power of the boycott was just as appealing to the APWR as it had been to the Citizens Council in years past. By the beginning of summer, there were already more than 30 chapters functioning from Liberty to Grenada.

The white fundamentalists in McComb—plagued endlessly by wild disinformation—were convinced that the Communist Party was exploiting black people for the benefit of its own agenda, and the apocalyptic threats of integration and amalgamation were just over the next hill. Never did a break in the editorial hogwash appear when the hysterical white citizens might have taken a deep breath and composed themselves.

Furthermore, the potential of Klan terrorism was never fully divorced from moderate minds.

It became painfully obvious to the pro-integrationist minority living in Burglund and Baertown that changing a law on paper alone was not going to alter generations of deeply ingrained bigotry. Unrestrained Enterprise-Journal articles, mainly the handiwork of Charles Gordon, but nonetheless approved by Oliver Emmerich, were reckless as they hammered emotional absurdities into the undiscerning minds of men with dynamite and shotguns.

Purely stated, this was a recipe for disaster, as antiquated views remained quite popular in the wooded river basin midway through the 1960s. Even the slightest inkling of public liberalism could still have dire consequences in Pike County.

An unavoidable metamorphosis, still unborn, would be required to change the collective mind of the Camellia City, but until then, there would be a great deal of anger and sorrow felt over the coming months.

As the most rabid segregationists manned the ramparts of the citadel, the starry-eyed COFO invaders would soon understand all too well that a long struggle for victory still lay ahead.

With unfounded fears looming in every direction, the melodramatic townspeople urgently needed to let go of the past.

However, escaping the ghosts of their Confederate ancestors was proving difficult. Emotional instability had reached a fever pitch, and McComb was now prepped for a lengthy series of explosive events.

The eerie calm that had followed the passage of the Civil Rights Act was about to be replaced by another wave of violence, and the unimaginable terrorism that Bob Moses had foreshadowed a few years earlier was on the verge of fruition.

McComb native David Ray is writing his first book on McComb's intense role in the Civil Rights Movement, "Mississippi's Masada: How A Race War Created the Bombing Capital of the World." Email him at [email protected]. Sources for available upon request.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus