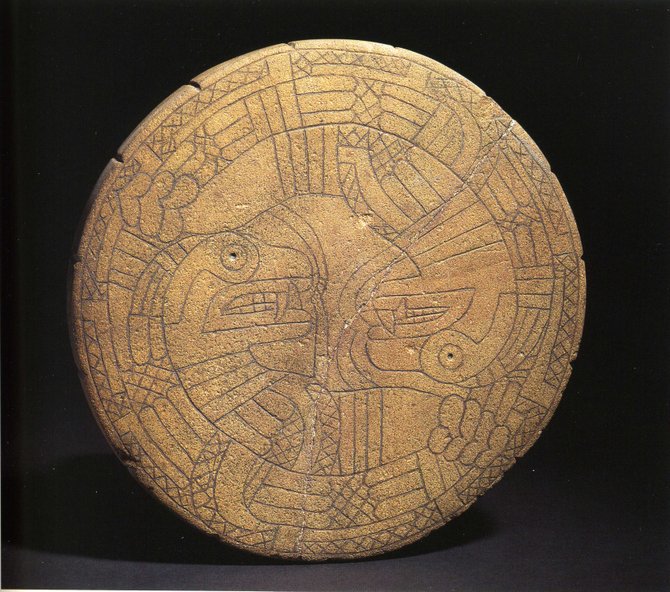

This disk, made of brown sandstone and found in Issaquena County, proves that Native Americans were not the primitive people many think they were.

If your description of Native Americans includes "primitive" or "savages," listening to retired archeologist and Jackson resident Sam Brookes will blow your mind. His interest in American Indians dates back to his Virginia childhood and his hobby of collecting arrowheads.

"I set out to be a writer," he says. "But then I realized I had no experience in anything and nothing to say and didn't have much technical expertise in writing."

That realization made Brookes drop out of college for a few years. Eventually, his hobby led him to pursue archeology at the University of Mississippi, where he earned his bachelor's and master's degrees in the field. His first job out of school was with the Mississippi Department of Archives. Brookes' career continued with the Corps of Engineers in Vicksburg and finally, with the United States Forest Service, where he was charged with setting up an archeology program.

"We found a few Indian mounds we didn't know we had," he says. Dating the mounds was problematic. Prior to the 1980s, dating methodology required artifacts, and the mounds didn't provide much. With more sophisticated methods, archeologists established that some of the mounds in Mississippi date to 4500 B.C., predating the Egyptian pyramids. Other people were still building mounds when Europeans arrived in the 16th century.

"These people were much more complex than we thought. ... We had envisioned them as hunter-gatherers," Brookes says of his college courses: no mounds, pottery, agriculture or bow-and-arrow. "But they did have mounds, and not only mounds, but mound groups."

Native people built many of the mounds and tools with "imported" materials, such as large rocks not endemic to the Delta. Jewelry and garments were made of shells and pink flamingo feathers. That indicates widespread trade and specialized artisans. These civilizations never invented the wheel, but they had cities, government, religion and shared fables, and they farmed. Some could recite their matriarchal lineage for generations.

Mound cities were similar to villages surrounding a castle. The mound was the highest, most defendable site, with concentric zones defining social strata—political and religious leaders, crafts and trades people, farmers and so forth. Water—moats—often surrounded the mounds. Archeologists haven't discovered all of the mounds' purposes, though. They include burial sites, and some were purely ceremonial.

"They were approaching a state-level society that (archeologists) call Chieftains," Brookes says. "That's what Hernando De Soto found when he rode through the Southeast."

Of course, European explorers also killed off many of the people, if not through outright violence, with the diseases against which the natives had no defenses. Many fled north, among them the Choctaw.

"Their legends tell of coming out of the mounds," Brookes explains.

For a time, French explorers lived with the natives at the Grand Village of the Natchez Indians in the state's southwest corner, which archeologists believe is the original mound. "Every site in America comes from that one site," Brookes says. The natives eventually rose up to fight off the invaders, but were ultimately unsuccessful.

"Fortunately, a lot of (the mounds) are left," Brookes says, even after property owners tore many down, mainly to build roads. Most are on private land, but the prospect of replicating Louisiana's successful mound trail is motivating owners to preserve the sites. Mississippi is planning a Mound Trail, similar to the Civil Rights and Blues trails, in the Delta and Natchez Bluffs areas, which Brookes hopes will launch in 2015.

"It's a win-win situation," he says.

Much remains unknown. The exploration of the mounds is an ongoing collaborative effort, with Ole Miss working in the north Delta, the University of Southern Mississippi exploring the southern part of the state and the University of North Carolina working in the Natchez Bluffs area.

Brookes leads mound tours out of Rolling Fork, with this year's tour scheduled for Oct. 25. Rolling Fork—the home of bluesman Muddy Waters, the site of the bear hunt that led to the original Teddy Bear and a Civil War site—is a veritable smorgasbord for history buffs of all sorts.

Sam Brookes is this year's speaker at the annual Ross Moore History Lecture at Millsaps College (1700 N. State St.) Oct. 7 at 7 p.m. Tickets are $10, $5 for students and are available online at millsaps.edu/news_events/arts_lecture_series.php.Call 601-974-1130 for more information.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus