The proximity of West Capitol Street near Poindexter Park to downtown underscores how essential building up west Jackson could be to growth in the capital city and the metro. Photo by Trip Burns.

As the sun sets on a steamy, cloudy Friday afternoon, the intersection of West Capitol Street and Ellis Avenue stirs to life. One man makes several trips to a nearby gas station for bags, sometimes stopping to talk to a blonde woman wearing short denim cutoffs. Just east is one of the main entrances to the Jackson Zoo and Livingston Park. Crossing guards near Barr Elementary School hold vigil and occasionally signal to motorists mind the 15-mile-per-hour speed limit in the school zone.

Further east up Capitol toward downtown sits historic Poindexter Park and its surrounding neighborhood. Around the turn of the century, a street trolley was installed to carry residents from the city center to Poindexter Park, the westernmost edge of Jackson at the time. The neighborhoods that branch out from Capitol Street have always been unique for Mississippi.

Doctors, attorneys, traveling salesmen, shop owners and top executives in some of the city's most prominent businesses once lived here. Historians note that most of the homes were built for working- and middle-class families to rent and, that as far back as the 1910s and 1920s, African Americans and whites more or less lived side-by-side.

"The conditions which are normally expected to separate groups of people and neighborhoods—conditions of economic class, race and home ownership versus rental housing—all appear very blurred," states the Poindexter Park Neighborhood Association's application for state historic status, submitted in 1995, "but are very clearly defined in other places of similar age in Jackson."

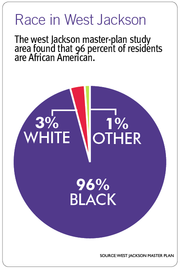

Today, once you cross over Gallatin Street going west, the neighborhoods along the Capitol Street are still occupied by working-class people although the racial dynamics have become almost uniformly African American. And as Jackson's population, and therefore, its tax base, has shrunk over the years, the city has had a difficult time maintaining the area.

Denise Wilson lives in the Pecan Park neighborhood and helps out at a friend's business, the name of which she asked to not be published. In the 11 years the small business has been operating, Wilson said she's watched the neighborhood through its ups and downs. She casually mentions that the store her friend owns has been burglarized twice and recently had the front windows broken. She drives a reporter down one crumbling street where three elected officials own properties. Ahead of a visit from First Lady Michelle Obama to Pecan Park Elementary in 2010, Wilson recalls public-works crews patching up the street and resetting the window dressing for Obama's benefit.

"Mrs. Obama does not pay property taxes here, but I do," Wilson said. She remains embittered by the sight of abandoned houses, the crumbling side streets, the presence of prostitution and the fact that businesses struggle despite sometimes heavy traffic counts.

Wilson jokes that sometimes she considers cancelling her cable subscription because, from her vantage point, she sees plenty of drama unfolding every day. "Why turn on the TV when you have a soap opera right here?"

Thinking of a Master Plan

If Wilson has had a front-row seat for the decline of West Capitol and other parts of west Jackson, she and other residents now have an opportunity to have a starring role in its comeback. By no means is Capitol Street the city's only major thoroughfare in need of some tender, loving care but for many reasons, the stars are aligning, and things are happening from the old Mississippi Capitol building to Interstate 220.

The renewed interest has resulted from several efforts, some of which have been long-running and some of which have begun only recently.

Take, for instance, Voice of Calvary Ministries' real-estate development arm, which has acquired vacant lots and abandoned homes and helped developed hundreds of affordable homes in the area. Meanwhile, spurred in part by murmurs that the zoo might move across town, new life has been breathed into a group called the Zoo Area Progressive Partnership to pull the zoo into efforts to revitalize the historic neighborhoods it anchors.

As of this year, the Jackson Police Department and Hinds County Sheriff's Office deployed what they call a long-term community-policing program adopted from Louisiana's capital city. In the short time the program—which had been called BRAVE but is now known as MACE—law enforcement agencies and neighbors report a drop in total crime.

Against this backdrop is the effort, ongoing since March 2013, to draw up a west Jackson master plan. The result of a disaster-planning grant, Voice of Calvary brought in Jackson-based Duvall Decker Architects to perform a study in a small area bounded by Fortification Street and U.S. 80 north to the south and Gallatin Street to Ellis Avenue from east to west.

Roy Decker, one of the firm's principals, calls it a grassroots rather than utopian visioning process.

"It's not all about new buildings. It's actually about policy, social organizations. It's about strategic developments that change values for the positives, that coordinate institutions, that does many things," Decker said. "It's a means to an end, but the end is blurry. The ends are in the hands of the residents."

The residents met at west Jackson churches, businesses and nonprofits, residents where they threw spaghetti at the wall, so to speak, in hopes that some of the ideas would stick.

During one working session held in February, participants suggested things like edible gardens, fruit groves, bike loan centers, better grocery stores, jazz concerts, farmers markets, roller rinks and a roller coaster. Many of the suggestions dealt with common sources of aggravation, such as housing, including more affordable and higher quality single family and mixed-income housing as well as more housing options for Jackson State University.

Duvall Decker commissioned planning interns to go about collecting mountains of data. The results are in the form of an hour-long presentation that the firm has been showing to groups around west Jackson that highlight some of the area's biggest challenges—and opportunities.

Under the Microscope

It's easy to see why west Jackson residents might feel like specimens in a Petri dish. Patti Patterson, who lives in west Jackson and was recently confirmed to the Jackson Zoo Board, says residents are suspicious of the motives of Decker and Phil Reed, Voice of Calvary's executive director, both of whom are white.

Some of those suspicions might not be completely irrational, said Patterson, who is African American.

"This community, they've been studied to death, but there's never any implementation," Patterson, a former Ward 5 council candidate, told the Jackson Free Press recently.

West Jackson is full of the kinds of challenges that social-science careers are built on, and the master plan takes all of it into account. With west Jackson housing most of the city's services for homeless people, the study plan attempts to get its arms around the homeless problem in Jackson. Decker notes that homeless people travel a "circuit" of services that includes breakfast at Galloway United Methodist Church, stops at the Opportunity Center, Stewpot and, finally, one of the homeless shelters for the evening. Breaking the circuit could have dire consequences.

"If they look for a job, they give up a meal or a bed," Decker said at a recent community meeting. Although the actual number is likely higher, the most recent point-in-time count from 2013 found 571 homeless people in Jackson, and many of the organizations that serve them are located in West Jackson.

In some Census tracts, median income is between $9,000 and $10,000, far below the state's median of $36,000. In the study area, Duvall Decker found that 40 percent of the land is either vacant land or abandoned property, and ownership of most of the real estate is concentrated in the hands of just a few owners, many of whom live outside the city. However, of the occupied homes, there are roughly equal numbers of owner and renter-occupied homes—a positive sign, Decker said.

The plan also looks at public transportation. Most routes the city's public transit system, JATRAN, travels appear to be holdovers from when most people worked in downtown Jackson, suggesting that an analysis that considers current trends might be needed.

Decker says while the study considers social concerns as well as economic opportunities, those problems won't be solved by one developer, and he is keenly aware of the skepticism that community residents have toward outsiders.

"West Jackson has been studied," he said, echoing, Patti Patterson, "(and) has had fairly manipulative property-acquisition strategies so that anybody coming into west Jackson talking about planning is going to be met with some mistrust."

The fear is that a powerful, shadowy developer is behind the curtains and orchestrating the removal of poor residents so that they can build expensive lofts, wine and cheese stores, and hipster coffee houses. In other words, gentrification.

Gentrification occurs when young, monied people start moving into a poor part of town, attracted by cheap land prices. Soon, amenities that cater to such people follow, which attracts more young, monied people, driving up housing demand and, therefore, property values and rents to levels that working class people who live there cannot afford.

Mukesh Kumar, interim program director for the Department of Urban and Regional Planning at Jackson State University, believes that the fear of gentrification occurring in West Jackson is probably overblown.

"People shouldn't be concerned with gentrification per se. They should be concerned with the competence of people who are in charge of addressing it," he says.

Kumar points to the study area and its high percentage of vacant land as evidence that west Jackson can accommodate as many people as want to live there. And other cities have gotten in front of gentrification with initiatives that keep people from being pushed out of their neighborhoods. In Philadelphia, Pa., for example, low-income senior citizens can have their property taxes frozen so that they don't incur an unsustainable tax burden in the event property values rise. In the city of Cleveland, Ohio-based manufacturer Sherwin Williams donates house paint to low-income citizens to keep their properties up to code.

The professor said the best way to stave off gentrification is to make the people living in west Jackson feel like they had a hand in its re-visioning. For example, planners could ask students at Barr Elementary School how to make the crosswalks they traverse every morning and afternoon more colorful.

"That way they own the street. They feel like the street is part of them," he said.

JPD's M.A.C.E. in the Hole

Also fueling suspicion that something sinister is afoot in the Capitol corridor is the fact that local police have started experimenting there with an initiative they hope will lower crime. If it works, they plan to roll it out city-wide.

Modeled on a program started in the capital of Louisiana, Jackson police and the Hinds County Sheriff's Office first deployed the B.R.A.V.E. program in a section of west Jackson from West Capitol Street to Interstate 20.

Jackson's approach to BRAVE (which is being renamed to Metro Area Crime Elimination, or MACE) is slightly different than how it was conceived in Louisiana. Both are long-term strategies, but Baton Rouge's program calls for more community-based policing, based on the Ceasefire model used in some 50 cities around the country of building relationships with residents and, sometimes, gang leaders.

The conception in Jackson also focuses on so-called quality-of-life issues, enforcement of which was the centerpiece of the policing strategy in New York City under Mayor Rudolph Giuliani and his police commissioner, William Bratton. Bratton, who left the NYPD to become chief of the Los Angeles Police Department, is a self-described adherent of the "broken windows" theory of policing, popularized by criminologists George Kelling and James Wilson in 1982, meaning that police would focus more on curtailing minor crime in hopes that it would reduce serious criminal behavior.

"My objective as commissioner was to focus on improving life in NYC by focusing on all details of crime, from graffiti to the high rate of murder, methodically using data and statistics to track patterns and to place police where they could be most effective," Bratton writes on his own LinkedIn profile.

The rationale of focusing on petty crimes is that people are less likely to commit violent crimes if they know something as simple as jaywalking could attract police attention. As part of the quality-of-life focus, Jackson has also moved building-code enforcement under the purview of JPD, the theory being that homeowners might be more inclined to get their properties up to code if failure to do so results in a visit from a cop carrying a gun as opposed to a building inspector with a clipboard.

Vance said the March shooting of death of 3-year-old Armon Burton helped spawn the program. Burton was killed in a hail of gunfire after people in his neighborhood quarreled, reportedly, over a missing dog, and exchanged some 30 bullets. The case remains unsolved.

The "broken windows" approach, however, has not held up well under further research and practice. For instance, University of Chicago professors Bernard Harcourt and Jens Ludwig studied the practice, finding that its ability to reduce violent crime is unproved. Its practice, they found, has a disparate effect on poor people, especially blacks and Hispanics—and even contributes to the well-known disproportionate drug arrests of African Americans (even as illicit drug abuse is as prominent among whites). Not to mention, data show that serving time for minor crimes actually increases recidivism—repeat criminal activity—once the offender leaves prison, which can include committing more severe crimes.

Jackson's BRAVE program, which JPD calls a long-term commitment, includes "quality of life" issues that residents often complain about, including dilapidated and abandoned homes, Vance said. The Yarber administration recently reorganized some city departments and moved building code enforcement to the police department to give the city more power to punish homeowners who do not maintain their properties.

"As opposed to going in there for a week or for a weekend. And the criminals know what you are doing. They just lay low and come back out. But with this approach, they don't know what they are doing. They are either going to have to shut down or move out," said JPD chief Lee Vance, who added that the neighborhood has seen a 42 percent decrease in crime in the past six weeks.

Democratic State Rep. Credell Calhoun lives in Pecan Park with his wife, Hinds County District 3 Supervisor Peggy Hobson Calhoun. He believes that the refocused law enforcement efforts are going to bring about major improvements.

"Every time I go out, I see (police) stopping somebody," said Calhoun, who serves as president of the Pecan Park Neighborhood Association and owns rental property in the neighborhood.

A More Perfect Union

No matter what the master plan ultimately has in it, the future of west Jackson's neighborhoods will depend on who is sitting at the table doing planning.

De'Keither Stamps, who represents Ward 4 on the Jackson City Council and is an ardent of booster of sprucing up the corridors that lead into the zoo, says he is encouraged by the fact that so many community stakeholders have been involved in the master-planning process.

"It's the perfect union between the neighborhood, the city, the zoo and several other interested parties," Stamps said.

For others, the union up until now has been less than perfect, however. Despite the talk about homelessness in west Jackson, Frank Spencer, executive director of Stewpot, which works with the homeless, says the organization has not been involved in talks about the master plan.

"Stewpot would love to be a part of that," said Spencer, whose organization at the corner of Capitol and Rose streets serves about 100 people every day through its day shelter, the Opportunity Center. "We have a vested interest in Capitol Street."

Among the noisiest opponents of the master-plan study is the Battlefield Community Neighborhood Association. For them, the sticking point is a Jackson State-proposed stadium. Decker emphasizes that the stadium is far from a done deal, but based on input from JSU and other community members, the master plan proposes a site near Battlefield Park.

The goals for the stadium have been lofty. For football games, the stadium would hold about 50,000, while it would pack 17,000 fans for basketball games and 21,000 for concerts. Additionally, the venue would include 75 skyboxes for rental, and JSU's Sports Hall of Fame would occupy the first floor. The original design includes 4,500 parking spaces. Another 2,000 are located in garages downtown where shuttle buses can help on big game days.

Janice Adams, president of Battlefield Park's neighborhood association, says she and her neighbors are concerned about their neighborhood being over run with commercial development spawned by the building of a stadium.

"The stadium, we don't want it in Battlefield. We wish they would take it somewhere else. We don't want it anywhere near our neighborhood because we feel like it's going to cause a lot of problems for us," Adams said. Decker says a community meeting specifically for Battlefield Park is planned in the upcoming weeks.

Patti Patterson, who has attended many meetings on the plan, acknowledges that it's been difficult to get neighbors involved. She says she's canvassed her west Jackson neighborhood to invite people to planning meetings, but has had little success.

Calhoun, the state representative and homeowner association president, says he has had similar difficulties, but he's less concerned with who would move into the neighborhood than with their commitment to improving it.

"You don't really care who fixes it up as long as they fix it," he said.

Still, some people, like Denise Wilson remain wary of the changes. As much as she wants to see the momentum sustained, she does worry that businesses like hers might be jettisoned for newer, shinier establishments that might start moving in once development really heats up.

But Kumar believes that a rising Capitol Street would benefit everyone, especially if demand for housing were to increase in Jackson.

"Given the momentum that west Jackson has, if some major demand shift were to happen, it would be the first location off the block," he said.

Comment at www.jfp.ms/westjxn. Email R.L. Nave at [email protected]. Learn more at www.facebook.com/pages/West-Jackson-Master-Plan.

Comments