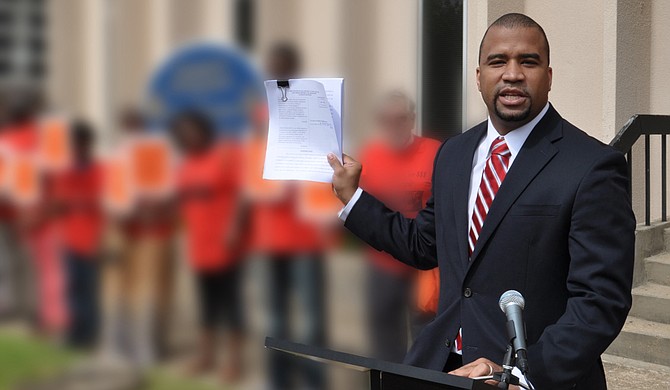

Jody Owens, managing attorney at the Mississippi Southern Poverty Law Center, criticized the vice president of a private prison company in court for not having more detailed knowledge about a riot at Walnut Grove, which she oversees. Photo courtesy Trip Burns/File Photo

Since pleading guilty to armed robbery in 2012 and being sentenced to eight years in prison at Walnut Grove Correctional Facility, J.E. says he has seen correctional officers trafficking contraband, drug use, daily gang fights, sexual assaults (of which he says he was a victim and why the Jackson Free Press is not using his full name) and at least three riots.

The most recent riot took place on July 10, 2014, when J.E., who holds an associate's degree in nursing and holds several other medical certifications, was conscripted to help triage injured prisoners, some of whom had to be airlifted to University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson.

"It was just chaotic. It was something you would think to see in a move, but this was reality. It was a sight," he testified in federal court in Jackson last week.

J.E. testified that one of the victims he treated begged him not to leave his side, fearful that the guards would let him die. Earlier in the hearing, when lawyers played videos of the riot that showed prisoners being kicked and beaten, sometimes with plastic milk crates and once with a microwave oven, J.E. would not look at the flat-screen monitors, not wanting to relive the memory.

The video was the centerpiece of a case brought by the ACLU National Prison Project and Southern Poverty Law Center on behalf of Walnut Grove prisoners alleging that the Mississippi Department of Corrections fails to keep people in their custody safe from violence.

Located in Leake County, Walnut Grove opened in 2001 for children convicted as adults in criminal court, and has been the subject of nearly ongoing scrutiny for civil-rights violations. In 2010, the ACLU and SPLC sued over conditions and won a settlement for their clients that included promises from MDOC to improve conditions and reduce violence at the facility. That consent decree requires periodic monitoring from an independent reviewer.

Three years later, and operating under a new private operator, prisoner-rights advocates find that Walnut Grove is still a violent place, with practices that violate the U.S. Constitution's prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. MDOC disagrees and recently filed a motion to terminate a federal settlement.

Thomas Friedman, an attorney from Phelps Dunbar representing the State of Mississippi, said during his opening statement in U.S. District Judge Carlton Reeves courtroom: "You can't try this case because of what occurred. ... We urge the court to look at what the condition of the prison is today. They want to try a facility that doesn't exist anymore."

Walnut Grove is still very much the same violent place it was when the parties settled the case, plaintiffs allege. "In three years, MDOC has never yet been in compliance with this consent decree," Margaret Winter, the associate director of the ACLU's National Prison Project, said in court.

But over the three days that they presented their case, attorneys for Walnut Grove prisoners did more than argue whether MDOC and Walnut Grove had violated the Eighth Amendment; they put private prisons themselves on trial as well.

Training Days

At he time of the original consent decree, Florida-based GEO Group Ltd.—the nation's No. 2 private-prison company—ran Walnut Grove. Today, Management & Training Corp., the third-largest corrections-management firm in the nation, headquartered in Utah, holds the contract.

The strategy of the plaintiffs' lawyers, who presented their case between April 1 and April 3, was to show how MTC's business practices—namely, a profit motive—create an environment that relegates prisoner and staff safety to the back burner.

Marjorie Brown, an MTC vice president who oversees wardens at the four prisons the company manages in Mississippi and one in Florida, said that despite telling prison after the July 2014 riot "we forgot how to do our jobs," the company terminated a half-dozen staff members. Brown, who is also an MTC shareholder, also said she is still confident that the company can meet the terms of its MDOC contract.

Brown also said MTC employees earn, on average, less than state workers but that the starting pay for correctional officers recently went up at MDOC's urging to between $10 and $10.50 per hour. Foes of prison privatization say lower wages, less rigorous training, understaffing and high turnover can all undermine safety at prisons.

Another video from the July 2014 Walnut Grove riot, taken from a camera mounted inside a guard station, shows correctional officers attempting to deploy tear gas into the housing pod where the riot was taking place. In an apparent malfunction, the canister went off inside the booth and the guards cleared out for approximately a half hour, as the violence continued in the housing unit.

Jody Owens, managing attorney at the Mississippi Southern Poverty Law Center, argued in court that the video demonstrates that MTC's guards were improperly equipped—the guard station lacked gas masks—and trained to respond to the riot. Brown, the MTC official, said she had not seen the video and was not aware that the gas canister had gone off in the guard booth before she took the stand in court last week.

"Private prisons are doing everything on the cheap," the Rev. Jeremy Tobin, a member of the newly formed Clergy for Prison Reform, which opposes privatization in the corrections industry, told the Jackson Free Press. Tobin's group believes profiting from the incarceration is immoral.

The private-prison industry bloomed amidst the political ethos of the 1980s that encouraged elected officials to get tough on crime and to hire private companies to run basic government functions more efficiently. Privatization peaked during the Great Recession when governments were desperate for ways to save money and balance their budgets.

Privatization also invited temptation for corruption. Earlier this year, in the same courthouse the Walnut Grove hearing took place, former MDOC Commissioner Christopher Epps pleaded guilty to taking kickbacks from a Rankin County businessman named Cecil McCrory who briefly owned a company that provided commissary services to prisons and jails. McCrory was also a consultant to companies that did business with MDOC, including MTC.

Eldon Vail, the former commissioner of the Washington (State) Department of Corrections and the plaintiffs' expert witness, told the court that in his opinion MTC is "not paying attention to correctional basics" designed to keep prisoners and staff safe. Vail also characterized Walnut Grove's response to the July riot as "pretty profound levels of incompetence."

Vail also cited a lack of training, including in verbal de-escalation techniques, and lack of encouragement of prisoners to participate in educational programs, such as general-educational equivalency, vocational training and substance abuse counseling.

MDOC's attorneys declined to speak with reporters during the hearing. Grace Fisher, MDOC's spokeswoman, told the Jackson Free Press that the agency does not want to comment on evidence that will be presented in court. The hearing was originally scheduled to take three days. However, the defendants—MDOC—will present their case in a few weeks, attorneys said.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.