Last night's Jackson City Council meeting all but jumped the shark when an aide to Mayor Tony Yarber walked into the chamber carrying a bag full of bottled water to distribute to council members and city staff who, at that point, had been talking for about three hours.

The refreshments arrived in the middle of a tense discussion of Yarber's proposed emergency proclamation, which he said would help the city respond more efficiently to infrastructure problems, including water-line breaks that have prompted nearly 100 boil-water notices since the start of the year.

When the water arrived, City Council Vice President Melvin Priester nervously joked that he only drinks the city's tap water-- a reference to a new marketing campaign, complete with a billboard on the interstate, designed to assure Jacksonians that the city's water is fine to drink.

Perhaps realizing the irony and the optics of drinking bottled water while trying to convince people that Jackson's water is the best in the state, other members of the council also renounced their bottles as city public-works Director Kishia Powell quickly reclaimed several of the plastic bottles.

It was a much-needed moment of levity. It was also a defining metaphor for what the city is going through right now with its infrastructure and the discord over how to address it, much less pay for it all. At the end of the night, the council delivered a resounding message to the Yarber administration, which had asked the council to approve a proclamation declaring a civil emergency so that he could better marshall resources to start fixing stuff.

That message was no.

Only one member, Ward 3's Kenneth Stokes, backed the mayor's play because he believed it would help patch potholes, which are a menace to cars to and are anathema to Jackson politicians running for reelection. Charles Tillman abstained, but seemed to be aligned with the rest of the opposition (Ward 7 Councilwoman Margaret Barrett Simon did not attend). Their uneasiness stemmed from the fact that no one is entirely sure what authority the mayor has to declare a municipal emergency and what that authority entails if he does have. And even if what Yarber says is true, that the declaration will put the city in line for funding from external agencies and expedite public-works crews turning dirt in the city, council members aren't sure what the fiscal and legal implications will be.

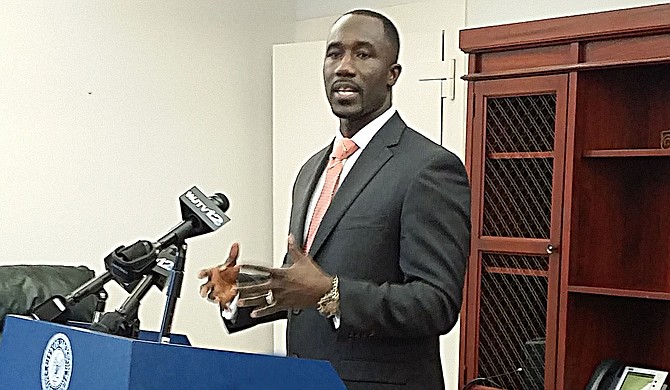

"In the climate of our state, if we relax procurement laws, that puts us in trouble," said Ward 6 Councilman Tyrone Hendrix of his reticence to approve the proclamation.

Furthering confusion was Yarber's insistence that emergency work would continue no matter how the council voted. At the same time, the mayor also quibbled with the inference that the proclamation is little more than a symbolic gesture. In fact, Yarber argued, having the council's imprimatur on his declaration would help the city get into rooms with state and federal influence-makers with whom the city might not otherwise have an audience.

In defense of his initial emergency declaration, Yarber said his administration "changed the paradigm" and started a national conversation on what constitutes an emergency.

"We're going to go to work either way," the mayor said before the vote.

Most immediately, that work will include repairing a water line fissure at the Chastain water tank, which officials said is in "imminent danger" and, if it fails, could leave thousands of people without water.

Funding options include a $2.5 million loan from the Mississippi State Department of Health that the city might not have to pay back if certain requirements are met. Then there's the roughly $12 million from the 1-percent sales tax that remains unspent as the 10-member sales tax commission mulls the comprehensive infrastructure master plan that Jackson developed.

Similar to the national conversation about dipping into strategic petroleum reserves when the price of gas spikes, Stokes also suggested the city consider using some of its fund balance -- a percentage of the city's revenues that state law and city ordinance requires the city to keep in an emergency reserve fund.

The council and mayor seemed open to exploring that idea, but took no votes on Stokes' suggestion. After the meeting, Yarber told reporters that his administration might still issue emergency declarations on a per-project basis, but that the council's no vote would not affect the city's ability to respond to crises.