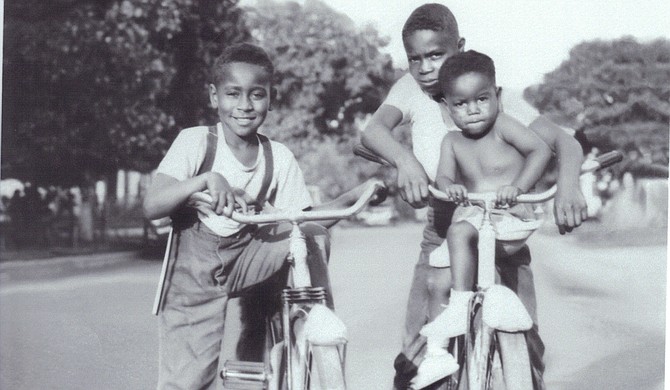

Cousins Emmett Till (left) and Wheeler Parker (back right) wheel around Argo-Summit, Ill., with family friend Joe B. Williams (front right). Parker said this photo was taken some time between 1949-1950. Photo courtesy Wheeler Parker Jr.

"That's Bobo's ring," 12-year-old Simeon Wright said.

He was standing next to his father, Moses, who went by "Mose," in their front yard in east Money—a small town in the Mississippi Delta. The county sheriff had brought the ring by their house to confirm Mose's nephew's identity on Sept. 1, 1955, the day after Emmett Till's body was pulled out of the Tallahatchie River.

Simeon's words were enough confirmation. Someone had murdered his cousin and thrown his body in the river. Till's face was so badly beaten and decomposed from the water that it was difficult to identify him at first, but the ring confirmed what Mose had said the day before standing over the body: it was Emmett Till.

Till was born and raised in Chicago, and the 14-year-old was visiting the Wrights in Mississippi that August. Emmett had let Simeon wear the ring earlier in the week, but Simeon had given it back because it was too big for his hand. The ring had belonged to Till's deceased father's, evidence of his identity that would prove fruitless in the months to come.

What Happened at Bryant's Grocery

The events of Wednesday, Aug. 24, are often misrepresented. Simeon, his brother Maurice and the two cousins from the North, Wheeler Parker and Emmett, decided to go into Money after picking cotton all day. Maurice drove.

Wheeler went into Bryant's Store to buy something, and Emmett followed him, Simeon says now, but once Wheeler left, Emmett was alone with the owner's wife, Carolyn Bryant, for a minute before Maurice sent Simeon in to get him. What happened between the boy and the 21-year-old woman for the brief time they were alone is unknown now to anyone but her, but that time period was short, only a minute or so Simeon says.

Simeon says that while he was in the store to get Emmett, his cousin did not say anything out of line to Carolyn, and paid for his items and left. Carolyn followed the boys out, walking north toward where her car was parked.

The boys were not in any hurry to leave—until Emmett let out a wolf-whistle as Carolyn walked toward her car.

"That's the reason we ran—we couldn't get to our car fast enough," Simeon says.

The boys were about halfway back to Mose Wright's house when Maurice pulled the car over. They saw someone following them. Three of the boys jumped out of the car, running out to the cotton fields to hide. Simeon lay down in the backseat. It was a false alarm, just a neighbor going home, but the boys were spooked. Till got scared when he saw his cousins' reactions, after returning to the car.

"Please don't tell Uncle Mose what I've done," Till told them, understanding the gravity of the situation. "I don't want to go home."

Till's whistle likely would have been harmless in his Chicago hometown, but in the Mississippi Delta, his actions were taken quite differently. Mamie Till-Mobley had warned her son of southern customs, but Simeon says it was just like Emmett to test the boundaries.

"He was a happy-go-lucky guy, always laughing," Simeon says. "He had been taught how to act down here, but with his personality, that was a challenge."

Carolyn Bryant later told a different story of what happened in that moment alone with Emmett Till, and before the trial, she said that Till touched her waist and wrists and made advances at her. Simeon says it would have been impossible for Emmett to grab her waist because you couldn't get behind the counter and that the story she told of Simeon dragging Till out of the store was not true.

The woman, who is still alive and living in another state, did change her story years later, Simeon Wright says, admitting she over-dramatized her account of what happened.

'If You Just Let Me Live ...'

The boys had forgotten about the incident by the weekend and never told Mose about it. Early on Sunday morning, after a Saturday night out in Greenwood, Emmett Till and his cousins were back in east Money at Mose Wright's home, asleep in two rooms. Suddenly, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam, who had a pistol in his hand, banged on the door, demanding to see Till.

Bryant and Milam were half-brothers. Bryant was married to Carolyn and owned Bryant's Grocery. Milam had also run a store in Glendora that burned down the year before. The Milam-Bryant family was raised and stayed in Tallahatchie County, mainly running general stores.

Wheeler Parker, Till's cousin who had also travelled from Chicago to visit his uncle, remembers that night vividly.

Parker was staying in the room next to Till's and when the men burst into his room that night, he thought his life was over. When the men left his room, Parker made a promise to God that set him on course for the rest of his life.

"If you just let me live, I'll do what's right."

Bryant and Milam found Till in the next room, which Simeon was sharing with his cousin. When Simeon opened his eyes, he saw two white men standing at the foot of his bed. He recognized Bryant immediately but did not know the man holding the gun.

Milam told Simeon to lie back down and go to sleep while Till got dressed.

Simeon lay in his bed, without a clue what was going on. His mother came in to plead with the men, saying she'd give them money. They claimed that they were going to take him out, whip him and bring him back, Simeon says.

Emmett said nothing, pausing only to insist that he needed to put his socks on with his shoes, but otherwise following the men's orders.

A woman that Mose Wright later said publicly was Carolyn Bryant was in the truck that night with Bryant and Milam to identify the boy. Mose also said there was another black man on the porch that evening who hid his face. Simeon did not go out to the porch that night, but he remembers his father saying a man was on the porch, likely the black man who showed Bryant and Milam where Mose lived.

What happened next remained a secret, veiled in half-truths for years. In research done for his 2005 documentary, "The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till," Keith Beauchamp discovered that 14 people were involved in the kidnapping and murder of Emmett Till that night. Beauchamp says Till was taken to Clint Shurden's plantation in Drew, Miss., which is northwest of Money in Sunflower County.

Milam's half-brother, Leslie Milam, managed the plantation, and he along with others were present that evening and likely participated in the beating and torturing of Till, Beauchamp says.

Beauchamp found that five African American men were forced to be involved, whether that meant holding Till down or cleaning up the mess afterward. The white men likely did not plan to kill Till initially, but things got out of hand, according to witnesses Beauchamp found.

On their way back to Glendora, his research found, Bryant and Milam stopped at the river and shot Till, tied a cotton gin around his neck and dumped him into the Tallahatchie River. An FBI autopsy on the exhumed body in 2004 confirmed that Till died of a gunshot to the head, but he had several other head wounds indicating that he was badly beaten before the final blow.

Mose Wright reported the abduction to the sheriff's department on Sunday morning, according to Devery Anderson's book "Emmett Till: The Murder that Shocked the World and Propelled the Civil Rights Movement." Anderson found that the sheriff, George Smith, seemed to know right away who the two men could be as soon as Wright mentioned "Bryant."

Smith arrested Bryant on kidnapping charges that same day, after Bryant admitted to taking the boy and dropping him off to walk home. Milam was arrested the following day, also on kidnapping charges.

Till's mother got the news Sunday morning via Curtis Parker (another cousin who had arrived that evening and was in the house the night Till was taken, Simeon says). Parker called his mother, Willie Mae, in Chicago that morning, and she broke the news to Mamie, Anderson writes. Mamie considered taking a train to Chicago, but Wheeler Parker arrived late that evening, not wanting to stay in Mississippi any longer. He began to tell what he knew.

Till's body was found three days later on Wednesday, bloated, disfigured and barely recognizable. He was pulled from the Tallahatchie River with barbed wire around his neck, as well as a cotton-gin fan, and multiple gashes and wounds, including a bullet hole in his face.

Mose and Simeon identified his body and then, after some complications, the body was sent back up to Chicago to his mother. His body arrived in Chicago on Friday, and reporters for Ebony and Jet magazines Simeon Booker and David Jackson were at the train station. Jackson took the infamous picture that ran on the Sept. 15 cover of Jet. This photo and Mamie's decision to have an open casket for her son's memorial were the publicity needed to fuel national outrage, protests and movements in the coming months.

Indicted, Then Freedom

Meanwhile in Sumner, a grand jury indicted Bryant and Milam for the murder of Till, and their trial was set to begin in Tallahatchie County where the body was found. They would be tried on the murder charges first. The state prosecuted the two men, calling Mamie down from Chicago as a key witness in the trial to counter a false rumor out that the body wasn't Till's.

Mose Wright's testimony was a highlight of the trial. Mose was able to identify Milam when asked to do so on the stand.

"There he is," he said, extending his arm fully pointing at Milam across the courtroom, a black-to-white gesture that was unheard of in the Jim Crow South.

Despite the evidence and testimonies of eyewitnesses, Bryant and Milam's defense continued to stress that the body was unable to be identified and was too decomposed to possibly be Till's. Tallahatchie County Sheriff H.C. Strider had cast public doubt on the body's identity despite having signed his death certificate. The jury of 12 white men came back with a "not guilty" verdict a little over an hour after deliberation started.

Mose Wright took his family and moved north almost immediately. Simeon says they started packing the Saturday after the trial and moved on Monday. Simeon was upset for years—the verdict had the most profound effect on him.

"I was so sure we were going to get a conviction because we were eyewitnesses, but I got a taste of what the Jim Crow system was like—something I didn't know," he says now.

Bryant and Milam were also tried on the kidnapping charges that fall and acquitted despite their public confessions to Sheriff Smith before Till's body was even found.

The incredible miscarriage of justice in that Tallahatchie Courthouse in the fall of 1955 set off a movement. Two weeks later, Rosa Parks would refuse to give up her seat on a public bus in Alabama.

Mamie Till-Mobley went back up to Chicago and finally had time to grieve the loss of her only son. Chris Benson, a professor at the University of Illinois, helped her write her memoir, "The Death of Innocence."

"She mined her grief for a mission in life," Benson says in an interview. "And learned that we all have a unique purpose."

After the trial, besides the occasional speaking engagement, Till-Mobley went on to become a teacher, teaching in Chicago public schools for more than 20 years.

By 2002, she had retired, but Benson was able to learn most of her story in long sit-down interviews, sometimes reading chapters back to her because her eyesight was failing. He says she was grateful to have her story down on paper.

"She was able to leave her with a certain level of peace, knowing that her story would live on," he says. Benson completed Mamie's memoir following her death in 2003.

Confessions, Lies and Truth

A year after they were acquitted and protected from double jeopardy—the law that protects a person from being tried again on the same charges—Bryant and Milam sold their story to Look magazine for a 1956 article. The men confessed to killing Till, saying he had provoked them with stories of being with white women and taunting them.

Filmmaker Beauchamp's reporting years later proved their confession to be false. Beauchamp found 14 people involved with Till's murder, including two black men thrown in jail during the 1955 trial so that they wouldn't be able to testify.

Beauchamp researched the case for 20 years, and the enormous injustice served in Till's case kept him fighting for a federal investigation. In May 2004, he got his wish, and the FBI re-opened an investigation into the Till's murder. Beauchamp's documentary, "The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till," was released in 2005.

Beauchamp and Alvin Sykes, a civil rights lawyer, worked with FBI investigators and, by 2006, the FBI delivered their report to Joyce Chiles, the attorney over the Fourth Judicial District in Mississippi. The state was responsible for putting the case before a grand jury.

The FBI report contained information that could be used to indict Carolyn Bryant on culpable manslaughter charges because Beauchamp would be able to prove that she knew and understood the danger Emmett Till was in and did nothing to stop it.

Beauchamp says he found two African American men who were boys back in 1955 that Bryant and Milam picked up for Carolyn to identify. Neither one was Emmett Till, so they were let off.

There had also been a warrant out for Carolyn's arrest back in 1955 because witnesses said then she was involved with the kidnapping, but she never served time. Sheriff Strider did not pursue her arrest because she had two young boys, according to Anderson's research.

In the end, the grand jury found insufficient evidence to charge Carolyn in 2007. Beauchamp believes the case wasn't handled properly and disagrees with its outcome.

Despite Till's case closing for good, a congressional bill, the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act of 2007, became law in 2008. It granted funding for the FBI to reopen unsolved or unjustly tried civil rights violations that occurred before Jan. 1, 1970. The nicknamed "Till Bill" expires in 2017, and Beauchamp says he hopes that "Till Bill 2" will become a reality in the future, with no cutoff or end date to investigate cases.

Sumner's Apology, Reconciliation

In 2007, members of Tallahatchie County came together to form the Emmett Till Commission and made the first public apology for their community's role in the injustice of Emmett Till's trial.

The public apology, made on behalf of the people of Tallahatchie County, did not go over well with everyone. Many people felt that Till's case was dropped in their laps, because the crimes did not occur in their county; most of the crimes were committed in Sunflower and LeFlore Counties.

Sumner was the site of the trial, meaning 12 white men from the county made up the jury that deliberated only a little over an hour to find Bryant and Milam not guilty for a murder they later confessed to.

Tallahatchie County's population today is 56 percent African American and 41 percent white. Sumner is home to about 300 people with a fairly even divide between the black and white community; 51 percent of the population is white; 47 percent African American.

The Emmett Till Commission consists of nine African American and nine white community members who are committed to some type of healing and recognize the injustice that was done back then.

Willie Williams is one of the commission members. He was born in 1955 in LeFlore County. The trial was well underway less than an hour from his childhood home. Williams is the pastor at Rollins United Methodist Church in Webb, the small town south of Sumner. Williams, who is black, learned about Emmett Till from his grandmother, who was acquainted with Crosby Smith, Till's uncle. Williams says those conversations never went beyond the home, however, largely out of fear.

"Some people didn't want you to talk about it, and people didn't talk about it publicly," he says. "And black people really didn't talk about it."

Williams says he has spoken with African American men who were the same age as Emmett in 1955 and lived in the area at the time. He says a lot of them left the Delta after the trial; many migrated north and left out of fear, he says.

Till's murder and trial drew national media attention because he had come down from Chicago and was a younger kid than many victims of white violence, Williams says.

"There was a lot of people here whose lives were taken that no one ever heard about," he says.

The Emmett Till Interpretive Center is a part of the effort to ensure that Till's legacy is not forgotten. It is located directly across from the courthouse where Bryant and Milam walked free.

De`Vante Wiley has interned at the Interpretive Center for the past two summers. Wiley's investment in Till's legacy became personal a few years ago when he found out that he is related to the Wrights through his mother's side of the family. "Two years ago, my grandma went to a funeral in Chicago with my family members and found we were related to Emmett Till," he says.

Wiley's reaction was shock, and he is still working through what it means to him deeply. Wiley, who is 21 and a sophomore at Jackson State University, grew up in Greenwood, the most populated city close to Sumner, about 40 minutes south on 49E, now also known as the Emmett Till Memorial Highway.

Wiley distinctly remembers how old he was when he learned about Emmett Till growing up. His great-grandmother told him the story once when he was 9 years old and again when he was 11. Despite learning about Till at home, he does not recall learning about him in his Greenwood High School history courses. What he does remember, however, is spending an entire month covering World War II and only a week and a half on the Civil Rights Movement.

"It's kind of common around here; they really don't teach or endorse teaching civil rights in public school—so students are really lost," he says.

Wiley says it's possible that a decent amount of his classmates never learned about Till, either. He says Till's story is important not just because of the horrible injustice but because of the good that came out of it, too.

"We can always talk about the Civil Rights Movement, but where did it come from?" he says. "It started with a 14-year-old boy brutally and unnecessarily killed, and the killers were able to walk away free—that's what started the Civil Rights Movement in my opinion."

What followed Till's lynching was a black-freedom movement from Rosa Parks and bus boycotts, to marches in Selma, to speeches on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial and the passage of the Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act, all the way to the Black Lives Matter movement today in response to police killings of so many unarmed people of color. When asked if the next generation will know about Emmett Till, Wiley stops to think. His niece is a year old.

"By the time she gets to be 18 or so, they'll be talking about Trayvon Martin or Mike Brown, and Emmett Till might not exist," he says. "The people around Till's age right now dying? Those are the people they will be talking about."

What History Teaches Us

Scholars say understanding Till's death in historical context is important. While Emmett Till's death might have helped spark a reaction from Rosa Parks a few weeks later, the Civil Rights Movement had started as a legal struggle.

Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka legally dismantled segregation in schools nationwide in 1954. But it had little immediate effect on legal segregation. Benson says the crumbling of a "separate but equal" legal standard turned the South into a frightening place to live for the African American community, especially those who wanted to challenge the status quo. As a middle-class northerner, Till could not have arrived in the Mississippi Delta at a worse time, Benson says. Till tried to challenge the status quo, and he faced, instead, an area of the nation the most resistant to the massive legal change of desegregation.

Benson sees Emmett Till's life and death as the bridge between the legal battle and the mass social movement for civil rights. He wants Till's death to be seen as more than a racial struggle but wider as a power struggle. If so, he says, history can help inform what's happening now to young African Americans in the country.

"If we can see ethno-violence and hate crimes in that context, that it's about forcing a power hierarchy and keeping people in their place, then we can see the similarities between then and now," Benson says.

After 10 years of research, Anderson believes Till's name should be out there as much as Rosa Parks or Martin Luther King Jr. Regardless of conservative or progressive views, time or perspective, Anderson doesn't think even conservatives today would say that Emmett Till had it coming. But Trayvon Martin? Somehow, white people had a prejudice against him in their mind no matter the circumstances, Anderson says.

"We hide behind the fact that we have an African American president or that laws have changed, but that doesn't mean racism is gone," he says.

The same resistance to change was evident in 1955, too. Part of Anderson's research involved the backlash to the Brown v. Board decision and the polarization of the American people during the 1960s. Anderson says that baby steps of progress at the grassroots level were needed then to ignite the social movements of the Civil Rights Movement.

Living His Legacy

Emmett Till's life and death lives on in the lives of people close to him—even to this day.

His cousin's murder and the trial's miscarriage of justice opened Simeon Wright's eyes to the adverse world of race relations around him. He says that after the trial, he realized his own father couldn't vote. He saw black families, like his, still working in cotton fields and being "paid" small amounts but with little gain in society. The Wrights moved to a Chicago suburb back in 1955, and Simeon still lives in the area today.

Simeon continues to speak to both adults and young people, around Chicago and the U.S. He says that in the south side of Chicago, kids have never heard of his cousin. Simeon says Till's murder and trial are a part of America's history that all people need to understand. In a few majority-white high schools he's spoken to, the kids ate Emmett's story up, he says.

"They can't believe it happened in America," he says.

Wheeler Parker stayed in Argo-Summit, Ill., outside Chicago and is now the pastor of the Argo Temple Church of God there, the same church Emmett's mother attended before her death.

The night of Till's kidnapping is still vivid in Parker's memory. He says that the promise he made because of Till's life changed his own. Argo Temple Church of God started in Mamie Till and her mother's home back in 1926. Her positive attitude throughout the trial and after affected the whole family's spirits, Parker says.

"I can't afford to hate," he says. "I can't afford the luxury of hating because it controls you."

Parker is thankful for the progress African Americans have made in the past 60 years because coming out of slavery, he says, it's still difficult to get recognition as first-class citizens.

He works with a lot of young people in his church, telling them about history but without stirring up animosity. Parker has given 10 talks this year alone, including a trip to Mississippi in July. Parker believes that if Till's story is not remembered, we're subject to repeat it.

"You have to constantly revisit it and the price that he paid," Parker says of his cousin Emmett Till.

"A lot of times (people) can appreciate it more if they know the people that paid for the freedom we have; they need to know the story."

Comment on and read more Emmett Till coverage at jfp.ms/till. Email Arielle Dreher at [email protected].

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus