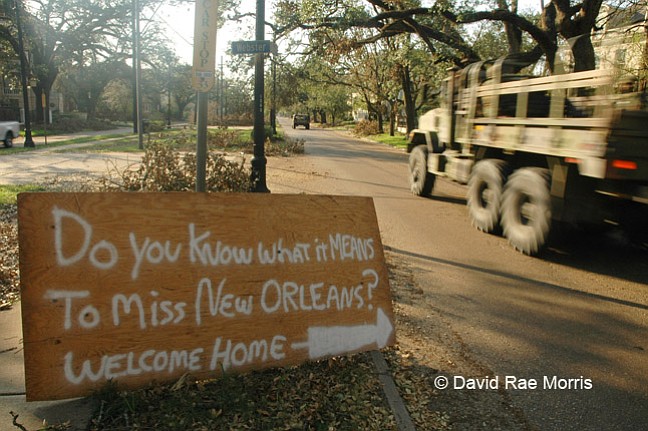

A military convoy drives along St. Charles Avenue in Uptown New Orleans, Sept. 8, 2005. The city was devastated when the levees broke after Hurricane Katrina made landfall in southeast Louisiana, flooding 80 percent of the city. Photo courtesy David Rae Morris

As we approached the 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, I found myself wanting to experience neither. I don't need to be reminded of the misery and death that Katrina wrought on New Orleans and the Mississippi Gulf Coast. I have never forgotten the destruction that enveloped my city—the smell and the heat and the silence. It is certainly amazing that it has been 10 years and the City of New Orleans seems to be thriving, for now, but I don't need to look back to continue to move forward.

That is not to say that Katrina didn't play a very important role on my life and career as a photojournalist and documentary photographer. Indeed, it was, and still is, the greatest story of my lifetime, and represents the largest body of work I have produced to date. It came out of nowhere and landed in my lap and for the better part of three years, I did little else than cover the aftermath of the storm. There were daily assignments, magazine covers, exhibits and lectures, press-club awards, and the shared respect from my colleagues and contemporaries for having successfully survived and documented that moment in time.

But by 2008, after three years of almost daily attention to the story, it all suddenly stopped. After Hurricane Gustav narrowly missed New Orleans in September 2008, the media grew quiet. Ultimately no one outside the city wanted to hear about the storm anymore. And I was left wondering where one goes after such a momentous catastrophe. How do you go back to a "normal" life after witnessing so much pain and suffering and incompetence?

My partner of 20 years had had enough of the debris and moved with our young daughter to a small town in southeast Ohio. I was invited to teach there for a while, but that eventually dried up, too. I returned to New Orleans to cover the celebration when the Saints won the Super Bowl, and it finally seemed like we had all turned the corner and the city had been lifted out of its malaise.

But then the Deepwater Horizon exploded in the Gulf, and all the pain and frustration and fear returned. While it was shorter lived, it was like a cruel deja vu.

In spite of the jokes my friends made about living in Ohio—often quoting Tennessee Williams: "America has only three cities: New York, San Francisco and New Orleans. Everywhere else is Cleveland."—it did represent something of an emotional oasis. My daughter could walk alone to a good public school with a student body representing 31 nations. I could sit on the front porch and watch the day go by, mow the lawn every two weeks in the summer, and shovel snow every now and then. It was nice to be able to have a fire. We rarely ran the air conditioning. We lived in a small, but loving university community. Still, we never sold our house in the Bywater, and I never gave up my Louisiana driver's license.

However, I want no part of the Katrina anniversary. I'll talk about it if someone asks me, but I know it will be a spectacle to rival the event itself. The media are descending upon New Orleans and the Gulf Coast long about now, doing their stand-ups and their in-depth stories and will leave town Aug. 30, never to return.

The story will truly be dead. At least in my lifetime.

Weeks in advance, the locals started addressing the impending anniversary. There have already been lectures and exhibits, and we will all continue to ponder how the city has changed and what the future holds. It is important to remember Hurricane Katrina and what she represents in our history. But I am reminded of it every day as I drink my coffee and look at my most iconic images hanging on the wall of my house.

In the intervening years since the storm made landfall, I have come to believe that my work covering Katrina represented something of a Faustian bargain. And now, as we prepare to revisit the pain and trauma once more time, I am torn between not wanting to listen and wanting to help lead the conversation. Katrina took a toll on all of us, but I am convinced that she took my soul.

I have been in and out of New Orleans for the last seven years, but we recently returned to live in the city again. While I was off with my family in Ohio or working on a film in Mississippi a good bit of the time, I lost touch with the spirit and rhythms of the city. But it has not taken long to get right back into the flow of things. And I am finding out it is the little things that welcome you home first—a train whistle or a tugboat on the industrial canal, the smell of coffee roasting, a crawfish boil or a short torrential rain.

But then I realize in reality, I never really left. And I know more than ever what we all know, what it means to miss New Orleans.

It was a Friday afternoon in August. I had just returned from the bank and parked in front of my house in the Bywater. I decided to walk to the corner store and get a soda and the paper.

As I pushed open the door, an arm reached out and pulled me in. It was an armed robbery in progress. Three guys with guns, bandanas covering their faces. It all happened very fast, and what scared me later was the fact that I had not been scared. They got the $80 I had just gotten from the bank, hit the store owner with the butt of the gun and then fled. I had been living in New Orleans for more than 10 years, and nothing like this had ever happened to me.

The police came and took everyone's statements. I called my partner, Susanne, to tell her what had happened and that I was alright. Later that evening, Big Chris around the corner at Vaughan's handed me two boxes of boiled shrimp, saying: "You didn't get robbed for nothing!'" Across the street, Ms. Sally offered words of comfort: "It'll be alright, baby, as long as that hurricane stays away."

Nobody had been paying attention to the hurricane. It had formed on Aug. 23 as tropical depression no. 12. By the time it passed over south Florida, it was a minimum category-one named Katrina. It was expected to turn sharply to the north and east and make landfall around Appalacacola. It wasn't until the 10 p.m. news on Friday night that people seemed to be expressing alarm. The hurricane had not turned. It was intensifying and heading directly toward the Louisiana Gulf Coast and the city.

I had never evacuated the city for a hurricane before. I had always stayed to cover the storm as a photographer. Their names run together now: there was Erin and Opal in 1995, Danny in 1997, Georges in 1998, Isidore and Lili in 2002. When Hurricane Ivan had threatened the city in 2004, eventually hitting the Florida panhandle, I ended up driving up to Jackson at 3 a.m. to be with my family, who had fled several days earlier. I did not want to be stuck without power, under curfew, and no story to cover. So I left. It was not an evacuation.

But this was clearly different. The robbery had thrown off my karma just enough that when I saw the satellite images of the storm taking up most of the Gulf, I didn't hesitate to say: "We're leaving."

The next day we packed our daughter and one cat (a second was outside and could not be found), and a couple of changes of clothes in to a suitcase and drove to Jackson. Surely we'd be back by Tuesday. We left late morning and there was already a buzz in town. The lines at the gas stations were a little longer, the traffic a little more congested. Still, we made it out of town without incident and arrived in Jackson safely, and set up with my father's widow, JoAnne. We did everything right. We filled our tanks with gas, got groceries and later filled the bathtub with water.

Katrina took a last-minute jog to the east on Monday morning, some say because of cooler waters at the mouth of the Mississippi, and made landfall in the tiny Mississippi community of Pearlington. It had moved inland and passed just to the east of Jackson, knocking out power in some neighborhoods, including where we were staying in Belhaven. Still, it seemed, at first, that New Orleans had dodged the bullet. Gasoline was not to be found, and cell-phone service was spotty at best. While I could occasionally make an outgoing call, my phone did not ring again for three weeks.

In retrospect, I often think that the robbery and our subsequent decision to evacuate had really been a blessing in disguise. I am not sure how I would have handled the turmoil of the city in the days immediately following the storm. And even if I had come away emotionally unscathed, I doubt I would have had the stomach to return again immediately. Because we were without power for a week in Jackson, we were spared the non-stop news coverage of the story as it unfolded on the national television news.

As it was, I took an assignment from The New York Times and accompanied a reporter and several preservationists to Biloxi and Gulfport looking at how the storm had affected historic properties on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Returning again a day later with a friend who had flown in from Israel, we went to Waveland and Bay St. Louis, and I was able to find friends gutting their house less than a mile from the beach. We had a candlelight dinner of MREs.

The wire service I had been freelancing for during the last five or so years pretty much abandoned me. "Our team is in place," I was told when I was finally able to reach the desk. But within a week, I had picked up a two-week assignment from another wire service, and by October began doing regular work for yet another. This kept me with steady work for the next few years, until the money became scarce and the storm largely irrelevant.

I did not return to New Orleans until Sept. 8. I rode into the city from Baton Rouge with Tyrone Turner, a contract photographer from National Geographic and our old friend Lori Waselchuk. We were not on deadline and under no pressure to file or transmit pictures to news agencies. We simply wandered around town.

We returned again the next day, and then Lori and I met in town late the afternoon of the 10th. By then, we had determined my house was OK. The flood waters had stopped a block away, but I did not venture inside until then. Our missing cat greeted me, howling as if to ask, "Where the hell have you been?"

I immediately began filling suitcases with clothes and packing my truck with negatives and hard drives left in the moment 10 days earlier. A National Guard Hummer came around the corner going the wrong way down France Street. I was wearing a collection of beat-up press credentials around my neck, the most prominent from my old photo agency, Impact Visuals, which had shut down four years earlier. Still they got me through every major checkpoint I encountered for the next three months.

The Hummer stopped. A stern-looking woman riding shotgun peered out at me from behind mirrored sunglasses. They were from the Oregon National Guard. I held out my driver's license. "I live here. I'm just taking some stuff out."

"Cool," she said.

So began my Katrina odyssey. I returned to Baton Rouge that night and to Jackson the next day, picking up another assignment for USA Today along the way. Many more would follow. I lived at a friend's house across the river in Algiers for awhile, and then moved back into our house, even though the power had still not been restored. I commuted back and forth between New Orleans and Jackson for three months until we moved back as a family at Thanksgiving.

Our city was in ruin.

"Somewhere between the piles of duct-taped refrigerators that line the streets, the wafting smell of rotting garbage and the passing Hummers of National Guard on patrol," I wrote on my website in October 2005, "there has to be some rational explanation for this situation. But I haven't figured it out yet."

The insomnia started almost immediately. I would return to Jackson after a week or two of covering the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and find myself wide-awake in the middle of the night. There was no logic or pattern. I would have several hours of deep sleep and then I would suddenly wake up at 2:52, or 1:47 or 3:12.

It was both the safest and most terrifying time of night. In the darkness, I was forced to confront the enormity of the disaster. The silent of the night brought me back to the deserted neighborhoods where I had wandered—Lakeview or Gentilly or the Lower Ninth Ward—photographing the remaining muck, debris and the interior of houses. The silence was deafening, the stillness overwhelming.

I remember one church in which the organ had been carried across the sanctuary by the floodwaters and encrusted with mud. I visited every month or so, and nothing had moved. Even the dried chunks of mud remained untouched after almost a year.

In the process of re-visiting these scenes, I was forced to confront my own demons, my hopes and fears. Was I doing good work? Was it important? Did anyone care? How long would it take for New Orleans to recover from the storm? How would the city be changed? What role would I play in the rebuilding efforts?

I would toss and turn for hours reliving these scenes before finally drifting back to sleep, often as the dawn began to envelop the nighttime sky. The pattern continued after we were all back in New Orleans and Susanne had returned to her job at Loyola and our daughter was back in school. Sometimes it was more prevalent than others.

After a while, I reached a point where I could no longer go into abandoned houses or even into ones that were in the process of being gutted. For weeks I was unable to drive across the bridge to the Lower Ninth Ward, just three blocks from my house, because it was too painful knowing all of the pain and suffering that had occurred there. There were residents I had befriended there whom I wanted to visit and photograph, but I just couldn't bring myself to do it.

I am a runner, and running helped me maintain my equilibrium. Up to that point, I had only run 5Ks and 10Ks, but by 2008 I had started to run half marathons and, in the course of the next six years, would run 14. It was a way to stay physically fit, but it also gave my mind a safe space to ponder where I had been and where I was going. I even ran the New York City Marathon on my 50th birthday and continued to run until an ankle injury forced me to slow down for a few years.

But the insomnia has remained. I tried the occasional over-the-counter sleep aid, and knew smoking a few hits off a joint would guarantee a restful sleep. But these were not things I wanted to get in the habit of doing every night.

After we had moved to Ohio, my sleeplessness became easier to deal with. I would get up early, make coffee and breakfast for my daughter and after she would leave for school, I would often get back into bed and sleep for another hour or two. Linear sleep, I concluded, was overrated.

I often used waking up at 4:30 a.m. or so as an excuse to go to a 6 a.m. spin class on Friday mornings. It was a delicate pattern but seemed to work. I rarely had nightmares or dreams that revisited the storm. The worst I had involved rising water. I was standing on the roof of a house, and the floodwaters were rising quickly. My dear friend and fellow photographer Lori Waselchuk was nearby on a lower roof. She was photographing and didn't realize the water was about to sweep her away. I forced myself to wake up.

Even after I began teaching in 2008, the storm was ever-present in my mind. It probably didn't help that I continued to hang several of more memorable images of the storm on the wall of the living room of our house. The most iconic, an image of a picket fence submerged in floodwaters, offered daily reminders of the storm. And every time I saw the same style of fence around town, I would have mini-flashbacks.

Ten years later, I still suffer from insomnia. I can get five solid hours of sleep, but after then, I am wide awake. I play a little game with myself, trying to guess what time it is when I wake up. I am usually within an hour, but I have been known to be only minutes off. Sometimes I am lucky and go back to sleep fairly quickly, or manage to actually sleep soundly thorough the night, but not often. In fact, as I write now it is the middle of the night, and I am finishing this piece at 3:30 a.m., having suddenly found myself wide-awake at 2:57.

As much as I want to avoid the 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, I know that ultimately I can't. She is so imbedded in my psyche that I have no choice but to accept it, for better or worse. Insomnia is one of the classic symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, and while I know that I don't and never had a full-blown case of PTSD, my experience covering the aftermath of Katrina certainly contributed to my current state of mind and my anxieties about the future.

Now that we are back in New Orleans, I am constantly being reminded of the storm—faded waterlines and National Guard markings—I have photographed and re-photographed over the last 10 years. And as we approach the anniversary, the fears and emotions have come into sharper focus. I drive by locations I photographed after the storm and remember the day and who I was with and what I was doing like it was yesterday.

I am hoping that come Aug. 30, these anxieties will begin to ease and that I will be able to once again move forward to address other issues in my life.

I guess I'll have to sleep on that.

Read more Katrina coverage from then and now at jfp.ms/katrina.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus