I was sleeping hard when a calf started bawling beneath the window of my room at the Samye Monastery Hotel in central Tibet. I'd been there for five nights and four days visiting the nunnery of Yeshe Tsogyal, (yea-shay so-gyal) an enlightened female practitioner born in eighth-century Tibet. It was the last morning that I would wake to the sounds of the barnyard animals behind the hotel. I had 40 minutes to get dressed, finish packing and lug my suitcases to the lobby. I'd have to hustle—everything took longer at 11,000 feet.

I grabbed the bottle of water I'd left on the night stand, twisted the cap and gulped it down. Between the altitude and high desert climate, I was constantly thirsty. No matter how much I drank, fluids left my body as quickly as I could put them in. I needed to hydrate for the hike up the mountain at Chimpu—my first climb since the Potala Palace in Lhasa. Nearly a week after, my knee was better but still sore.

Apart from that, I'd done well—no altitude sickness, just spaced-out. I checked the time—30 minutes left to get it together.

Pilgrimage, from the Tibetan Buddhist point of view, is supposed to be challenging. Enduring physical pain during it is considered a form of purification. The practices of traveling great distances by foot, sleeping outdoors in bad weather and prostrating every step of the way to a holy site seemed to induce pain. As a Western student of Tibetan Buddhism, I wanted to practice as a pilgrim but was unsure of the pain equals purification formula. Could I be a pilgrim with skepticism in tow?

Our group—also including three fellow pilgrims and our Tibetan guide and driver—left the hotel on time and began the 20-mile drive to Chimpu hermitage. The landscape of central Tibet was unbelievable, like driving through a National Geographic photo spread. Outside Samye, we turned on to the newly paved highway along the Tsangpo River. The two-lane road coursed a dramatic mix of imposing mountains, tumbled moraine and miles of sandy, dry riverbank.

As we drove downstream, the mountainside expanded and contracted, pushing the road out and around in a series of blind curves. The barren riverbed was piled high with windblown sand, forming a shifting field of traverse dunes. Framed beneath the endless sky at the top of the world, every view from every angle was spectacular.

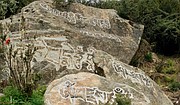

Chimpu hermitage is an ancient mountain retreat where a hundred or so contemporary yogis, monks and nuns live in seclusion. A dirt path with long flights of stone stairway winds up the mountainside, past tiny retreat huts and boulder-sized mani stones incised with "Om Mani Padme Hum": the mantra of Chenrezig, the Buddha of Compassion.

Visiting the caves along the upper ridge is said to bestow blessings, but that was not in my plan. I wanted to visit the cave where Tsogyal spent 12 years in retreat. The hike would be strenuous enough, about 4,000 vertical feet. Reciting the mantra of compassion, I put aside thoughts of distance and difficulty and began the climb.

Walking and breathing quickly turned into manual labor. To get enough oxygen, I had to work my lungs like baffles, and my hurt knee delivered a twinge of pain with every step. Determined to complete the practice, I limped along, stopping every 10 steps to catch my breath. Youthful nuns passed by, leaving me in the dust that trailed behind their maroon robes.

After two hours, I became unsteady with exhaustion. I stopped at a spring below the cave and drank all the icy water I could.

Starting up back up the path was like walking into a wall. Three hundred feet from Yeshe Tsogyal's cave, my resolve was gone, replaced by constant, sharp pain in my leg and knee. For a few agonizing moments, I considered giving up. As if sensing my anxiety, an elderly nun emerged from her retreat hut near the path. Smiling, she offered me a boiled potato, a common food that monastics share. I picked a small, brown gift from her dented pot and thanked her with folded hands. Kindness and a potato propelled me forward.

Tsogyal's hermitage was small, about 10 feet deep and 8 feet wide. Enclosed by weathered stonewalls on three sides, her cave looked like an archaic shed with a tiny wooden door at the entrance.

Dizzy with relief, I stepped into the dim little room. It took a moment for my eyes to adjust, but I found the stone bench. With a bow of gratitude, I sat down opposite a small altar, illuminated by a row of butter lamps.

Hundreds of years of soot had blackened the cave walls. I imagined the countless number of candles and lamps that had lit the lonely stone room, the infinite number of mantras uttered in the darkness. I imagined the hundreds of thousands of pilgrims who had followed the same path, made the same climb.

After a few moments, I stopped imagining and relaxed into the quiet of the cave. The oily lamps flickered; the silence expanded. With aching knees and arduous breath, determination and doubts, I rested in meditation and practice.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus