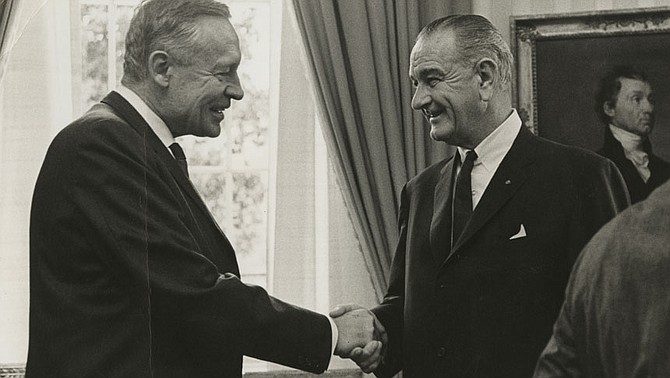

Fifty years ago this this month President Johnson's science advisors delivered the first warning about rising greenhouse gas emissions to a sitting president. On Feb. 8, he warned Congress about altering the atmosphere with carbon emissions. Climate scientist Roger Revelle (left) shakes hands with Johnson (right) in the Oval Office. Photo courtesy Roger Revelle Papers, Special Collections & Archives, University of California, San Diego

It is a key moment in climate change history that few remember: This week marks the 50th anniversary of the first presidential mention of the environmental risk of carbon dioxide pollution from fossil fuels.

President Lyndon Baines Johnson, in a February 8, 1965 special message to Congress warned about build-up of the invisible air pollutant that scientists recognize today as the primary contributor to global warming.

"Air pollution is no longer confined to isolated places," said Johnson less than three weeks after his 1965 inauguration. "This generation has altered the composition of the atmosphere on a global scale through radioactive materials and a steady increase in carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels."

The speech mainly focused on all-too-visible pollution of land and waterways, including roadside auto graveyards, strip mine sites, and soot pollution that had marred even the White House.

Within the year, Johnson would sign six new environmental laws during a period better remembered for the strife that led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the escalation of the Vietnam War. Johnson also that year established a dozen new national monuments, historic sites, and recreation areas; and submitted a draft nuclear non-proliferation treaty to the United Nations.

Carbon risk, of course, still stymies policymakers. But it was not ignored entirely in the wake of Johnson's "Special Message to Congress on Conservation and Restoration of Natural Beauty." In fact, the warnings and predictions given to Johnson from his science team proved remarkably prescient.

On-Target Estimate

The science on carbon dioxide as known at the time, including forecasts of warming and sea level rise, was detailed in a chapter of a report on environmental pollution issued later that year by the president's Science Advisory Committee. Pioneering climate scientist Roger Revelle chaired the sub-committee that wrote the chapter in the November 1965 report. While citing a need for better calculations with "large computers," Revelle's panel delivered a forecast on growing atmospheric carbon that proved on-target.

Coal, oil, and natural gas burning would lift atmospheric carbon dioxide between 14 percent and 30 percent by the year 2000, the panel estimated. In fact, CO2 increased 15.5 percent by 2000, and is 25 percent higher today than in 1965.

"Man is unwittingly conducting a vast geophysical experiment," the report said, echoing language Revelle first had used in a 1957 scientific paper when he was at the University of California, San Diego, Scripps Institution of Oceanography. "Within a few generations, he is burning the fossil fuels that accumulated in the earth over the past 500 million years."

Ken Caldeira, atmospheric scientist at the Carnegie Institution for Science's Department of Global Ecology, said the exchanges between scientists and the White House 50 years ago have significance for climate discussions today.

"To the best of my knowledge, 1965 was the first time that a U.S. President was ever officially warned of environmental risks from the accumulation of fossil-fuel carbon dioxide in the atmosphere," Caldeira said in an email. "This year will mark a half-century of Presidential knowledge of the risks of climate change. I wish I could say that there has been a half-century of concerted efforts to reduce these risks.

"The science of climate and the carbon-cycle that was reported to President Johnson in 1965 largely holds up today, demonstrating that climate science is a mature science," Caldeira added. "Climate scientists are still arguing about the details, but knowledgeable people have agreed about the fundamentals for a long time."

Cue to Johnson's Thinking

The only surviving member of the sub-panel, Wallace Broecker, geology professor at Columbia University's Earth Institute, said by telephone he does not recall work on it, though he might have been asked to review the chapter by Revelle, then at Harvard, and the other panel members, who were at Scripps.

As a young Columbia faculty member in 1965, Broecker had already begun what would be his seminal work on ocean chemistry and the carbon cycle; the chapter includes an appendix of detailed calculations on that subject.

A clue to Johnson's own thinking about his environmental message - and his concern about potential push-back he'd face from industry proponents - may be found in a telephone conversation he had three days before sending it to Congress. Johnson sought support for his environmental initiatives from United Auto Workers' union chief Walter Reuther, a recording of the phone call shows.

"Now my natural beauty message is going up Monday, and it is an eloquent thing," Johnson told Reuther. "We think it will be our best message." He added that White House speechwriter Richard Goodwin and his team had crafted the language with two figures who later would be recognized as icons of the conservation movement, Interior Secretary Stewart Udall and financier-philanthropist Laurance Rockefeller.

Congressional Master

Udall had two years earlier authored the book, The Quiet Crisis, about land and water degradation. Rockefeller co-founded the American Conservation Association, which later merged into the World Wildlife Fund. The two were then working closely with the president's wife, Lady Bird Johnson, on the environmental initiatives she hoped to make her legacy.

The president's message to Congress called for White House "Conference on Natural Beauty" to be co-chaired by the First Lady and Rockefeller, grandson of oilman John D. Rockefeller. Nearly 1,000 delegates attended the conference, which was held in May.

Johnson, well-recognized for his mastery of Congressional politics, knew his plan faced opposition - especially his call for devoting 3 percent of highway trust cash for purposes other than road building, such as the planting of trees and wildflowers on roadsides. Johnson urged influential auto union leader Reuther to meet with one of the most vocal opponents, Democratic Michigan Sen. Pat McNamara, the public works chairman. The president suggested he deliver the message that the state's workers supported cleaning up pollution, because in the end, it would sell more cars.

"Now you must not quote me," Johnson says. "You just must get the positive, affirmative message out... how we're going to have a real campaign to see America, go to Wyoming, go to Colorado, and get the kids out on Sunday afternoon... and we'll make more automobiles, and sell more!

"Now you're intelligent enough to take it from there," Johnson cajoles.

Faith in a Solution

The idea of ramping up car sales may seem counter to Johnson's warning about the risk of increasing fossil fuel emissions. But Johnson's message to Congress projects faith that the auto emissions problem was solvable. "I intend to institute discussions with industry officials...leading to an effective elimination or substantial reduction of pollution from liquid-fueled automobiles," he said.

It is not surprising that then-fledgling carbon dioxide science was overshadowed by the other monumental problems Johnson catalogued in his address: degradation of every major river system, eye-watering noxious air pollution in cities, an America where "skeletons of discarded cars litter the countryside."

In the following months, the president would sign the legislation most associated with Lady Bird—the Highway Beautification Act, which forced landscaping beside federally funded roads and removal of junkyards. Other 1965 laws included the Water Quality Act, the Solid Waste Disposal Act, and the Land and Conservation Fund Act. Among new protected areas Johnson established in 1965 were Ellis Island in New York, the Agate Fossil Beds in Nebraska, and the Pecos Indian pueblos site in New Mexico.

"There are more thinking people in America thinking of improving their land and their life at any period in America since I've known it," Johnson said in the eight-minute call with Reuther. "They're fussing about junkyards along the roads and pollution in the rivers, and the whole natural beauty thing. There've been more editorials about it, more garden clubs interested. I really feel it...If that's true, it's a good sign. It's something we want to build on."

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus