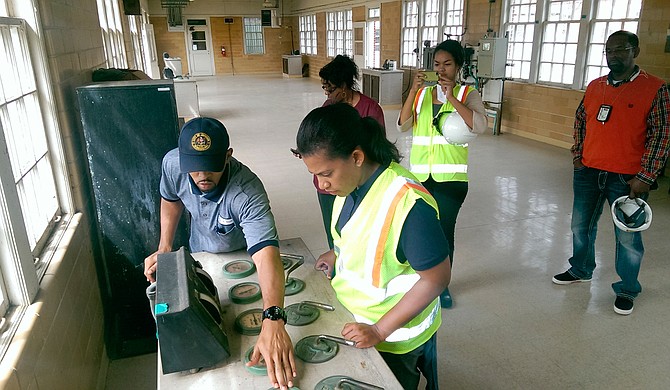

Kishia Powell learns how to clean filters at the city’s 100-year-old J.H. Fewell Water Treatment Plant from Terrance Byrd, the plant’s operations manager. Later that day, she also helped repair a broken sewer line, resurface a street, mop floors and process water payments, all tasks that fall under her direction as public-works director.

Kishia Powell, the city's public-works director, is in a 10-foot hole.

With her hair pulled back into one of her signature pony-tails and wearing gray boot-cut slacks, fluorescent safety vest and a hard hat, Powell uses a shovel to dig around the mouth of a busted sewer pipe parallel to the train tracks near Bullard Street at Ford Avenue. A crew of about 10 men will replace the collapsed section of concrete pipe with 350 feet of turquoise-colored PVC.

"Be careful, we'll have to replace you," one of the crew members shouts down to his boss, Powell, which draws chuckles from her and the other workers standing around the trench.

Later, Powell, who allowed a Jackson Free Press reporter to shadow her for part of the day, said it was exhilarating to witness and be part of the camaraderie between workers in one of the city's largest departments by total employees.

Reminiscent of scenes where a commander-in-chief visits troops in a conflict zone, Powell spent the morning touring facilities and meeting with workers under her command. The site visits capped off National Public Works Week and served to rally the troops ahead of the city council's consideration in the coming weeks of spending from the 1-percent sales tax and Mayor Tony Yarber administration's first-year infrastructure master plan.

In early May, a special commission approved a year's worth of spending after a couple hours of spirited debate—and at times sniping between Powell and Commissioner Pete Perry, a Republican operative and lobbyist—in what is known to city insiders as the year-one CIP (which stands for comprehensive infrastructure plan).

The repair plan is broken up into four pieces: drainage, bridges, streets and roads and water-line improvements. Because of disagreement among commissioners over parts of the overall plan, the city will spend $13 million in cash that the state Department of Revenue has collected since the spring of 2014.

The sales-tax money is only a small part of the more than $700 million shortfall for infrastructure upgrades, and the vast majority of it won't go toward the most visible symbol of needed groundwork—fixing the pothole. And considering that most of the burden will fall to short-staffed and poorly paid city work crews, it's no wonder that Powell spent the day glad-handing and taking selfies with her employees.

In short, Powell's job, for which she is the highest-paid person in Jackson government, is to help change the mindset of a whole city that a filled pothole is the end-all-be-all of good infrastructure management. At the start of the public-works week, which included a parade of new trucks through downtown, Powell told reporters after a press conference that there's no federal money for plugging up potholes.

"But when you start to address the pipes underneath, and you're dealing with utility cuts, and you can demonstrate that your streets are being torn up because of utility failures, then you can start trying to get the assistance that you need," Powell said.

Water Worries

Water is the linchpin, the root of and answer to a lot of the city's fiscal woes.

Jackson's Water and Sewer Business Administration, which collects more than $70 million a year from individual homeowners and businesses as well as other government entities, might be the largest and most profitable municipally owned utility in the state. Yet, the enterprise isn't the cash cow it once was. Over the years, the city and the number of people paying into has shrunk as age and Mother Nature have degraded an underground network of water and sewer pipes bigger than those of St. Louis, Mo., and Powell's former home of Baltimore.

The water pipes are in such bad shape that the city estimates 40 percent of the water it treats leaks out before it has any hope of spilling out of a faucet, where it can be collected as revenue.

Powell's trip to the J.H. Fewell Water Treatment Plant early Friday brought those challenges into sharp focus. Built in 1914, the plant pulls in water from the Pearl River and can process 30 million gallons of water per day, although plant officials said output usually hovers around 9 mgd.

In addition to old age, the plant is suffering from a shortage of operations staff, whose jobs include adding and constantly monitoring of turbidity (cloudiness) levels and balances of chemicals like aluminate sulfate and lime, testing the water and keeping 28 filters clean.

Powell helps backwash, or clean, one of the filters, which requires her wrestle open a series of heavy, cast-iron levers on a contraption that looks like it belongs in an alchemist's laboratory. Powell jokes that she's used to working in newer plants that perform the same process with the push of a button; another city plant, O.B. Curtis, has more up-to-date technology.

Plant officials told Powell that calculating the average cost to treat water on a millions-of-gallons-a-day basis is difficult because the Pearl River is "flashy," meaning the levels of pollutants vary wildly.

"It's really based on whatever Mother Nature throws at us," plant Operations Manager Terrance Byrd told Powell.

No one mentioned the fact that it is Jackson's dumping of millions of gallons of untreated sewage into the Pearl River that drew a federal lawsuit and put the City under a more than $400 million consent decree with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, another problem the 1-percent sales tax money is being marshaled to address.

Finding just the right mix of city money, 1-cent tax funds, and state and government assistance to dig Jackson out of its hole and appease citizens will require Powell, Yarber and other city officials to walk a tightrope.

Yarber said at a press conference last week that the city is considering "strategies that cause us to have resiliency so that we're doing the same things in 15 years, so that we're not having the same conversations about the same streets and the same water issues 15 years from now."