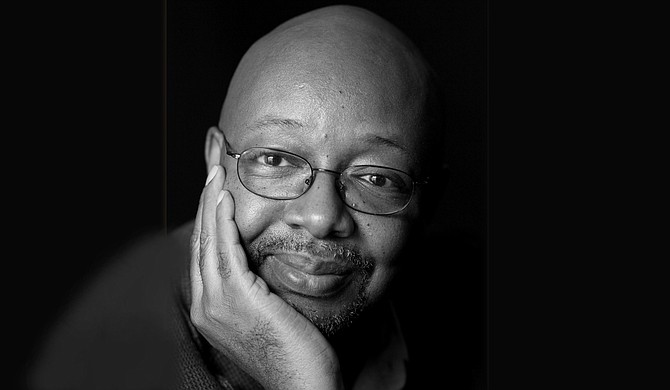

The assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and an attempted assassination of Barack Obama on the eve of his historic presidential win frame the third novel from Leonard Pitts Jr., a columnist for The Miami Herald. Photo courtesy Carl Juste/Agate Publishing

Leonard Pitts Jr.'s "Grant Park" begins and ends with a dream. In the opening scenes of Pitts' third novel, Malcolm Toussaint is stirred awake after dreaming about being a teenage activist, one where he saves Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. from assassination, which has been a recurring fantasy of his for the ensuing four decades. Forty years later, the nation prepares for an occasion that would have been unthinkable in 1968—the election of Barack Obama as America's first black president. Instead of reveling in the historic moment, Toussaint, a prize-winning black columnist for the fictitious Chicago Post, is in the midst of a professional crisis.

Disillusioned about writing about killings of unarmed African Americans by Chicago cops and reading racist reader emails that inevitably follow those columns, Toussaint pens one that states: "I'm sick and tired of white folks' bullsh-t." The rest of the novel hits on many of the themes with which Pitts, who, like his protagonist, is an award-winning syndicated columnist, grapples in his regular column.

Naturally, working for The Miami Herald (he lives in Maryland with his family), he writes a good bit about social issues, and politics, including the current presidential contest that includes two Floridians, former Gov. Jeb Bush and U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio.

Leonard Pitts Jr. will sign copies of Grant Park (Agate Bolden, $25) at Lemuria Books on Nov. 18 at 5 p.m. He recently spoke to the Jackson Free Press about race, writing and reckoning.

Does the climate of social unrest we've had the past couple of years make it easier or harder to be a black writer?

One of the reviews from Kirkus or Publishers Weekly or something said it is prescient, which is lovely to hear—that someone thinks you were ahead of the curve. Really, the kind of stuff we've been seeing the last couple of years has been going on all along. It's just now that we're focused on it. We're paying more attention to it, and cell-phone cameras have become so ubiquitous that it's on the news all the time. I don't know that current events really had a hand one way or another in making the book easier or harder to write. I just chose Chicago and a random police shooting, but we saw a shooting similar to what I describe happen in New York to Amadou Diallo. That stuff never quite goes away.

Do you feel a responsibility to write about these things when they happen?

You know that you've got the platform that there are things that need to be said. You've had enough experience at this to know what people are going to say in response, and it's a matter of 'Do I really feel like doing this?'" There have been times when writing the column when there's stuff that has to be said, and I know what (criticism is) going to come in, and it sort of kills your soul a little to read it. My poor assistant, who is white, just gets so upset. She told me once that 'I don't understand how you don't just hate white people.' I told her, 'I'd have to hate you, and you haven't done anything to me.' You write those columns because you've got an obligation to do it, you have a duty. I'll usually try to give myself a mind vacation where I write 'I love apple pie' or 'My mom was great' or something just to give myself a break from that kind of stuff. I suspect that, psychologically, it is probably not the healthiest thing for you to be banging your head against that brick wall all the time.

What's it like working on a column while working on a novel?

I don't know that there's a great divide. You mention accuracy, facts and fairness; I had to double check the novel for accuracy and, when I decided to fudge, to at least fudge knowingly. (In Grant Park) after the riot on Beale Street, there's a scene where Malcolm is walking the Mississippi River trying to get to a Holiday Inn. I went to Memphis and walked that route just to try to get a sense of what it would have been like—what he would have seen, what the terrain was like. Obviously, the river has changed a lot since 1968, but I wanted to get some sense what that walk would have been like. Fairness is part of it. I didn't want to paint my white characters as these one-dimensional people who were there more as plot devices than as actual people. I think a lot of the things that apply to a column apply, differently perhaps, in writing a novel.

I'm not a native Mississippian, and sometimes feel that I haven't earned the right to offer Mississippians my opinion. Who am I to tell Mississippi that they should change the flag? You grew up in southern California, live in Maryland and write a column for The Miami Herald. How do you navigate that?

I think you have to be fair, and you have to be sensitive to a reasonable degree, but I think it's hard to do the job if you're concerned about offending someone. Opinion is always going to offend somebody. Mississippi and—frankly, the larger South—is long overdue for a discussion about not just that flag but all the symbols of the so-called lost cause that it insists on embracing. I always find it fascinating that the culture of the south embracing two things—it embraces a sort of hyper patriotism and love for America, and it also embraces symbols of treason. I just find that really kind of weird. It's a sort of duality of consciousness that I've always found rather strange. I'm sure if I was in Mississippi I'd be in as much trouble as you get in or probably more because there is just stuff that is obvious to me that requires saying.

Have you been able to make any sense of that paradox?

Somebody mentioned, after Charleston in the whole discussion over the Confederate flag, where are there monuments to the cause that actually won the war and the cause that has been vindicated by history? We're wedded to this era of Civil War-era artifacts.

We're also wedded, which I find really troubling and also fascinating, to this notion about making the war about something other than what it was. It's been successful to an appalling and amazing degree when people all over the country, particularly in the south and particularly conservatives in the south now, say with a straight face that the war had little if anything to do with slavery, which is contrary to everything anybody who fought in the war—the leaders—said.

There's some emotional duality, some deep denialism at work in the south that sooner or later you're going to have to deal with. The thing about America is that we tend to put off our reckonings.

Was it Jefferson who said, "I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just and that his justice cannot sleep forever?" That's as succinct as you can have it put. You can deny, deny and deny, but at some point you're going to have to pay the bill for that. And that's what the Civil War was. The Civil Rights Movement was paying the bill for that denialism, and if we're not careful we're going to pay the bill again.

Comment at www.jfp.ms. Email R.L. Nave at [email protected].

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus