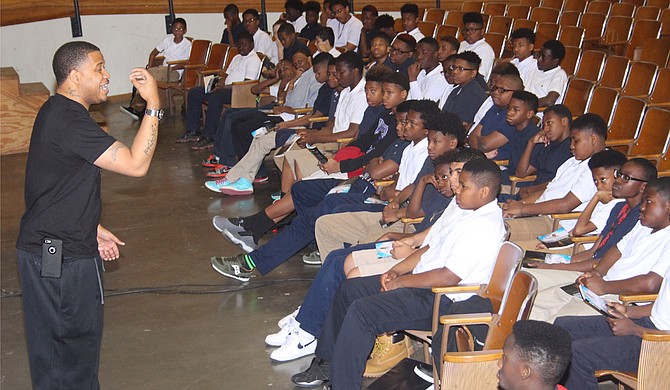

Tommie Mabry, who was kicked out of Whitten Preparatory Middle School more than a decade ago, told young men there to let music like that of Lil Boosie be the “passion of your ear, not your lifestyle.” Photo courtesy Jackson Public Schools

Tommie Mabry's world changed when he was shot in the foot in high school on a day he chose to skip class. When his doctor told him and his family that he might not ever play basketball again, Mabry took the initiative to be a better student and citizen. After playing out-of-state on basketball scholarships, he returned to Jackson to play at Tougaloo College, and graduated not only with academic honors, but the honor of being the first in his family to finish both high school and college.

Then, Mabry got an offer to teach at Whitten Preparatory Middle School—the same school that kicked him out when he was a middle-school student. Mabry, a 28-year-old author, motivational speaker and Jackson native, spoke before a group of at-risk Whitten Prep boys on Feb. 8 as part of a series of presentations related to Whitten Preparatory School's Men on the M.O.V.E. program. The program calls for "motivating, organizing, volunteering and engaging" efforts among young men who might be most vulnerable to the type of violence that pummeled Mabry's childhood experience.

Despite the love and attention of his family, Mabry's glamorized perception of drug dealers kept him out of school—he was kicked out of "almost every elementary school in JPS," he says—and on the streets.

"The first time I got shot, I was in fifth grade," Mabry told the crowd of boys, recalling the time his attempt at breaking and entering was met with three gunshots, one of which grazed his side. But, Mabry said, despite society's expectations for black men living in poverty to fail, success in life is possible, regardless of stereotypes. "I love (Lil) Boosie, but let that be the passion of your ear, not your lifestyle," Mabry said.

Mabry also exhorted the boys to be conscious of self-destructive behavior. If you stick behind what you know defines you, he said, no one can take that away from you.

"Be confident. Be determined. Be motivated. Be yourself," Mabry said.

Chinelo Evans, chief academic officer of middle schools in Jackson Public Schools, says for the presentation, the Whitten Prep counselors and administration chose 100 boys they felt really needed to hear Mabry's message. Principal Victor Ellis says that participatory students read Mabry's book, "A Dark Journey to a Light Future," to prepare them for his presentation. Nearly every boy in the audience held a copy, and referenced the book in their questions to Mabry at the end of the presentation.

"I think it went very well. I believe the students really were attentive, and I think he really connected with a lot of them because his life mirrored the life some of them are living right now," Ellis said. Evans agreed, saying that the small crowd size made the talk more intimate—and more powerful.

"It's important for us as educators that the students receive proper exposure to let them know that they have choices—and that they can do anything," Evans said.

Sierra Mannie is an education reporting fellow for the Jackson Free Press and The Hechinger Report. Email her at sierra@jacksonfreepress.com.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.