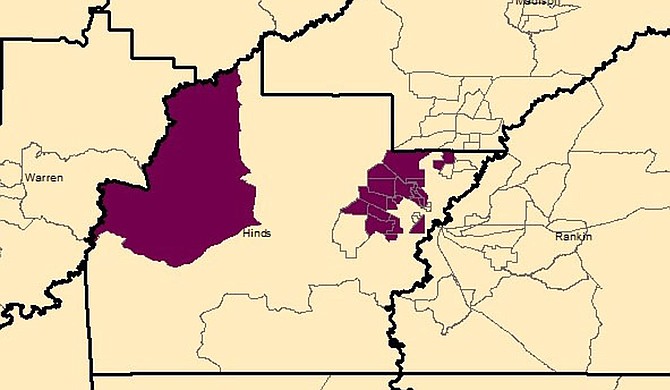

Food deserts border the west side of the Interstate 220 corridor and the northwest corner of Hinds County. (Note: this map isolates Hinds County and does not show food deserts in surrounding counties.) Visit the USDA’s website to see a full map of Mississippi’s food deserts. Photo courtesy Hope Policy Institute

The map of food deserts in Mississippi is staggering. At least a third of the state has regions considered "low-income census tracts" where a significant number of the residents are more than a mile (in urban settings) or 10 miles (in rural settings) from the nearest supermarket. In Hinds County, the entire northwest part of the county is considered a food desert.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture sets the definitions for food deserts, which are tracked in order to illuminate where low-income areas of states, counties or neighborhoods need help accessing healthy food.

Sen. David Blount, D-Jackson, introduced legislation in the 2015 session that would have provided tax incentives for grocery stores to enter communities considered to be "food deserts" by the USDA's standards. The bill, backed by several Senate Democrats, passed through the Senate and then died on the House calendar.

This year, Blount is reintroducing the legislation, and Rep. Jarvis Dortch, D-Jackson, is introducing the same bill in the House of Representatives.

The bill would authorize a job tax-credit for supermarkets with a $4 million cap. Blount said he first introduced the legislation last year when the Kroger in south Jackson announced it was closing in 2015. "People in low-income areas need access to quality grocery stores," Blount said.

Hunger Free Jackson held its first annual conference last week, and leaders in food networks that provide food to low-access areas of the state discussed strategies and ways to increase access to good, quality food. Blount and Dortch's bills would not just apply to the Jackson area, although food deserts affect two parts of Hinds County, the USDA data shows. The northwest corner of Hinds County and the Interstate 220 corridor are considered food deserts in the county.

Speaking at the Hunger Free Jackson conference, Catherine Montgomery, a program manager at the Mississippi Food Network, said the root of most problems with food in the state is access.

She helps run a summer program for the network, providing food for children who are usually on the free-and-reduced lunch program during the school year and might go without food in the summer.

"We can put a site in a county and think it's going to be very successful, but if a child has to cross a road or walk far, they're not going to get to that site," she said. "So it's important that we provide enough access to these families."

Rural Health Clinic Access

Rural parts of the state with little access to healthcare could benefit from two bills that would update an old part of Mississippi's healthcare law currently preventing some for-profit healthcare clinics from moving into the state.

In rural health clinics, a nurse practitioner can practice on his or her own as long as their collaborative doctor is 15 miles away.

Sen. Angela Hill, R-Picayune, introduced two bills to change this rule, so that nurse practitioners can collaborate with doctors anywhere in the state. Hill said with modern technology and telemedicine, this rule change makes sense and is timely for such a rural state.

"We don't have the luxury of waiting; we need to get business development and healthcare development to come to Mississippi," she told the Jackson Free Press.

Zach Allen, one of Hill's constituents in Picayune, works for the Children's International Medical Group, which would like to expand in Mississippi but cannot cost-effectively do so with the current law. The group cannot build a clinic more than 15 miles past a consulting doctor currently, and financially, this does not make sense because the group would have to bring in a pediatrician to each clinic.

Pediatrician salaries are costly, compared to setting up clinics with nurse practitioners in rural areas who can consult with doctors from any distance away. Allen's group specializes in clinics that have nurse practitioners or pediatricians. There are 34 counties in Mississippi that do not have pediatricians, a Mississippi State study found.

"Mississippi is the only state with a rule this restrictive," Allen said. "We have two new clinics in the pipeline, and I had to put them in Louisiana."

Allen said this legislation should not be a political issue and appeals to both political parties because changing the 15-mile rule would promote private business development in the state as well as bring healthcare to rural areas with no previous access to pediatric care. The Children's International Medical Group clinics accept Medicare and Medicaid patients, as well, so expansion into rural areas would not curb some from access to healthcare.

Sen. Hill said her legislation will not result in any detrimental outcomes for patients at all—the bills also do not require tax cuts or cost taxpayers.

"It's about access, convenience and people not having transportation to drive long distances to see one doctor or pediatrician," Hill said.

For more legislative coverage visit jfp.ms/msleg.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.