Jackson Police Chief Lee Vance (left) and Hinds County Sheriff Victor Mason fist-bump after the 2nd Precinct roll call as they talked on April 15 about Operation Side-by-Side that they were launching that night. Photo by Imani Khayyam.

JACKSON — This is Part 2 of the Preventing Violence series.

The 17-year-old who goes by the name Kvng Zeakyy was first arrested when he broke into Isable Elementary School near where he stayed on Florence Avenue in the Washington Addition. He and his buddy wanted to steal some laptops, but they only saw desktop computers when they got inside. And the boys weren't really big enough to carry those out of the school. Zeakyy was 9 and in the fourth grade there, and his friend was 11.

Then the cops came.

The bust turned into Zeakyy's first stint in the Henley-Young Juvenile Justice Center—or the "detention center" as young people who've passed through its (proverbially) revolving doors refer to it. The three-day stay there—in some ways a rite of passage for many poor young people of color in Jackson—was really the beginning of the child's discontent that eventually led him to sell dope around the Addition.

"I knew a lot of people in there," Zeakyy said in April. A couple of his older brothers' friends in the detention center told him they would protect him. "I cried and everything when I was in there." The guards, he said, scared him by telling him he would be in Henley-Young for 25 years. "I thought they were telling the truth."

We were hanging out and talking in Sheppard Brothers Park on Earth Day, the third time we'd met up at the same picnic tables there in recent weeks. This time, he kept playing with his large, loose watch because he had a meeting at 5 p.m. "sharp," as he had warned me in a Facebook message.

Zeakyy was, and is, a smart young man. Until he was in the fourth grade, he didn't think too much about what his family didn't have and was engaged at school. "In every subject, I made A, A, A, A," he said of his early school years. But, he added, "I was too young to know about struggle, what was really going on in my household, what was really going on in life, period. I thought life was about going to school, make a couple As, get a couple dollars, and I'd buy me snacks and stuff. For real."

His mother sometimes worked jobs such as housekeeping at nearby Jackson State University, to feed her growing house of kids, but often was out of work. Zeakyy, her second child, has two sisters and three brothers; his older brother is in prison now for armed robbery. The father of his little brother and one of his sisters lived with them for several years and did what he could, Zeakyy said, but it wasn't enough.

"When you get to a certain age, I'd say fourth grade because I went to jail when I was in fourth grade, the detention center, you want the shoes everybody else got and stuff," he said. "Therefore, you feel like you gotta take matters in your own hands to get it. ... I chose to go the opposite way when I was going the right way the whole time, but it made things worse."

But it wasn't home life that led Zeakyy to crime; they were poor, but it wasn't abusive, he said. "It was more about what was going on outside your home that made you feel like your home was rough. ... Your peers and whatever they push you ... not just bullying you in a physical way, bullying you through your mind."

Still, poverty can get the best of a kid. "Struggle is when you supposed to have a happy home with your family, but you staying with somebody else's family because you and your family don't have no home. When you did have a home, you didn't have no light. Y'all was using candles or something. You was hungry," he said.

"It's about what you know you should have, what's making you eager in your mind to do the other thing. It's real," he added.

Coming Home to the Washington Addition

A mother struggles, but helps steer her son to help other young men.

"The streets" had distracted Zeakyy by the seventh grade; he was in and out of the detention center and often suspended from school until he was expelled when he was 15. And he had regular run-ins with the police. Zeakyy describes a cop hitting him in the stomach when he was in handcuffs and another one busting his face and nose. That time, his mother saw him sitting in the squad car with a bloody nose and demanded to know what happened. The cop threatened to take her to jail, he said.

It wasn't about white cops picking on black kids, though. "They all different colors, a variety, wasn't no racist thing, just Jackson police gone beat your ass," Zeakyy said.

"If police will kill a man with no weapon," the teenager added, referring to the long list of unarmed black men police have killed around the country, "you think I want to say, 'Hey, how you doing today' to the police? I'm not interested in going near the police even if I'm in trouble. I ain't gone say it's because of the color of my skin; (it's about) the place I'm at."

That place is a poor, crime-infected neighborhood like the Washington Addition with limited opportunities where interactions with law enforcement are often toxic and punitive—especially with young black men suspecting of committing a crime.

More often than not, in Jackson and across America, it is a broken exchange from the outset, with both police and suspects believing the other is out to get them.

'You Can't Run from No Bullet'

Jackson Police Chief Lee Vance was wearing a salmon-pink Nike sweatshirt and looking bone-weary when he showed up at 3410 Fontaine Avenue on a Sunday night, March 6, in the wake of the fourth and fifth gun murders of that weekend. Samuel Davis, 21, and Janice Grayer, 51, both African American, had died after a shootout in the middle of Fontaine, at the intersection of Eminence Row, in the Virden Addition.

Davis took multiple bullets and died on the scene; police then believed Gray was caught in the crossfire and tried to drive herself to a hospital, but she crashed her car near Mayes Street and Bailey Avenue, and was pronounced dead on arrival at the University of Mississippi Medical Center. Another black male was hit, but lived, police said.

JPD found more than 40 shell casings in the street and a gun on Davis' body. "I'm sure there were witnesses, but whether they'll tell us the information is a whole other story. There were plenty of people out here, but no one has come forward, yet," Vance told reporters as captured by WLBT.

"Situations like this weekend test your resolve," added Vance, the chief of a mostly black police department who often seems conflicted and a bit angry over how to deal with gun violence among and against young black men in the city where he grew up.

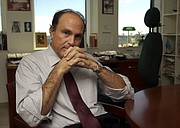

"Mississippi has some of the most liberal gun laws in the country, and the only thing you have to do in order to possess one is be 18, not be a convicted felon, and it'd be a legal weapon," he told me last summer in his office. "So I think it would be dishonest if I said that did not lend itself to the amount of guns that we have on the street."

Then the chief paused and added, "But my honest feeling is that you have to make a decision whether or not you're gonna point that gun at somebody and pull the trigger."

Davis, who police say was both a shooter and victim that night on Fontaine, was a friend of Zeakyy and other members of the "Undivided" group that former gang member John Knight started in the Washington Addition. The young men have all been in trouble, but have no felony convictions, and are trying to stay straight and avoid both committing violence and becoming a victim of it; their mentor Knight was shot six times when he ran the streets in the Addition. On the day I first met them, most of them wore black t-shirts with a tribute to their friend "Sammy" on the back with praying hands.

Zeakyy disagrees with the chief and others, such as Ward 3 Councilman Kenneth Stokes, who want to take firearms off people who live in gun-soaked areas like the Additions. Young people need guns to stay alive, he said, because they can't, or won't, call the police for help.

"I look at carrying guns as protection because police ain't there when a dude fires the first shot. If they are, he is not going to fire the first shot," Zeakyy says in the park. "... You can't run from no bullet. ... You'd rather be caught with (a gun) than caught without it, know what I'm saying?"

Zeakyy says the lives of young people in neighborhoods like his are in continual danger. "Some people carry guns for the wrong things, but a lot of people carry guns because if you don't carry a gun in Jackson, Mississippi, you gone get robbed or shot. People might leave you alone just because they see your gun," the aspiring rap artist said.

"Not carrying a gun ain't gone stop no killing," his fellow "Undivided" member, Jay McChristian, 19, suddenly interjected.

"Exactly," Zeakyy continued. "Not saying carrying one will, but if you know what you're doing, it will. It's not about who's got the gun first or who shoots first, or none of that. He can shoot first, but I can aim, and he can shoot and miss, and I can shoot and hit him, and I save my life. Or I can see him fixing to shoot and shoot before him and save my life."

The threat is real for people who grow up amid the struggle of life in the Addition, Zeakyy emphasized. "They beat up on you, they take their anger out on you if you ask me," he said of desperate people around him. Frustration then filled his voice.

"Police ain't gone be too much help. You think somebody shooting at you, police ain't gone be like, 'Move, son, I've got this' and start shooting for you. No! They gone wait 'til everybody get done shooting, and then lock everybody up, that's what they're going to do. It's just the truth."

From Vance's perspective, the truth is that too many men and women are shooting and being shot in neighborhoods flooded with legal and illegal guns—and the public expects police to stop shootings that are hard to prevent.

"In the city of Jackson, the type of murders that you (usually) have are when two people have a dispute, and they can't seem to solve the dispute other than one or the other picks up a gun and shoots the other. There are no indicators that are provided to law enforcement so that we may be able to intervene," said Vance, who grew up on Wood Street and has been on the force 27 years.

Still, the chief takes the ambitious stance that every other law-enforcement leader around the country seems to share: The police must accept the responsibility of preventing crime, including gun violence, rather than just respond to it after the fact. For one thing, the public expects it.

"That's something that I think is embedded in the psyche of society," Vance said last summer. "I mean, I don't know how you rid or even make people think alternatively to that, and I'm not sure whether that's not a fair expectation. Part of the problem is being strictly reactive in a police agency. You gotta be proactive, you gotta come up with a prevention plan if you want to be successful."

But, Vance emphasized, the police department is only the first responder to crime and cannot alone stop it, or ensure that criminals stay in jail or prison. It's as if the public, the media especially, only look to the police to stop violence—a random shooting happens, and it's the police's fault, he said.

"I don't care whether it's good, bad or in-between, I will sit down with you, and tell you the truth about what's going on," he said. "But you get tired of having to clean up somebody else's messes that don't even want to give you a dime to help you, right? But I get held, we get held responsible for it."

A few months later, standing on Fontaine Avenue in his Nike sweatshirt, Vance sounded despondent over senseless violence beyond his power to control. "This is a crisis weekend. We've got people that have no regard for human life carrying guns with bad intentions," Vance told reporters.

"Jackson, Mississippi, is a much better place than what we saw this weekend. We've got to be about proving that, but it's going to take more than police ...." The WLBT audio then cuts him off as the reporter introduces the next sound bite.

'Uncomfortable' Criminals

As the April 15, 2016, roll call wound up for Friday-night officers in the 2nd Precinct in the big windowless room inside the Metrocenter Mall, the police chief and the Hinds County sheriff sat down side-by-side at the back of the room to poke fun at each other and talk about a new joint crime-fighting strategy as uniformed JPD and Hinds County officers milled about. "It's a community-oriented policing concept," Vance told a Jackson Free Press reporting team, there for an evening ride-along. "All that really is is an attitude adjustment."

It's also a way to get more squad cars, each typically with one officer inside, driving through the city's neighborhoods. Ideally, Vance said, somebody sitting on her front porch would see a JPD or a Hinds car every 45 minutes. "The beat structure is designed for the presence of that police officer in that area; it's supposed to deter crime," he said.

"Operation Side-by-Side" is the first time the two agencies have worked together since both men took the top positions, Vance in 2014 after Tony Yarber became mayor and Mason last year after defeating one-term Sheriff Tyrone Lewis.

At one point, the two proudly fist-bumped each other as they talked about putting JPD's DART officers together with the sheriff's new Street Crimes Unit.

The beefed-up joint force—Vance declined to say how many officers it involved—will drive the city, watching for problems and creating a presence, rather than responding to 911 calls, which keeps cops in reactive mode and makes it harder to interact with residents (as does riding in cars). "Getting out into the neighborhoods, being seen, it makes the citizen feel safe, makes the criminal feel uncomfortable," Vance said.

"The number-one complaint I always got from people was this: 'I don't see the police enough.' They love that visibility," Vance said at the 2nd Precinct.

The teams will bring heavy enforcement to areas the brass thinks need it in order to deter crime—poor areas such as the Washington Addition where many residents, and not just criminals, historically distrust the police, regardless of the race of the officers. "If you're seen in these neighborhoods as being a servant and not an adversary," Vance said, "it's going to work out much better."

If the police act respectfully, residents are more likely to call them when they witness crime, Vance said, voicing a dangerous outcome of police distrust in often-targeted black communities throughout the country. When they trust the police, residents are more likely to call and say, "'I saw Joe Blow break into that house ... his cousin lives around the corner, and that's where they usually take that stuff,'" Vance said. Then, police can go there and have a "knock-and-talk": "'Hey, we heard you got some stolen stuff in here.' That in itself is effective," he added.

By April 10, it had been a violent spring in Jackson—18 homicides, most of them gun crimes—and much of it had occurred in poverty-stricken pockets of the 2nd Precinct. April 15 was a rainy Friday, and a JFP reporter and photographer rode along with a JPD sergeant, watching cops stop potential prostitutes and do pat-downs for drugs and weapons, as I tagged along with the chief in his SUV. He explained more about what the DART unit does, referring to the New Orleans Police Department and how each of its nine districts had a "strike force," similar to DART. Every week, each district commander would look at COMSTAT data and assign the unit to hot spots.

"It all goes back to the same concept that we were talking about with the old MACE project, the concept about (Sheriff) Vic's inner-city task-force thing: applying constant pressure to trouble spots to make the crime go away or prevent any more from occurring," Vance said while driving through the 2nd Precinct. "It's all the same concept; you can call it a quarter pounder with cheese if you want to, but it's the same thing, right? It's about applying resources on the concept that police presence is going to deter crime."

The teams made no major arrests that night, however, and did not do joint operations for another two weeks. But on April 28, Vance and Mason called reporters to the chief's office to renew their vows from two weeks before. Mason said Side-by-Side would continue: "Vance has the intelligence, and we have the muscle," he said. Vance said they would not only do weekend sweeps, but set up checkpoints during the week.

As television cameras rolled and reporters crowded in close, Vance declared their intention to bring down gun violence, but without repeating his earlier lament to me about how hard it is to take guns off anyone who isn't a felon. The operation is designed as a show of strength by law enforcement in areas, such as Beat 7 of Precinct 2—the Washington Addition—where they expect the traditional spikes in crime as school gets out and the summer heats up.

As I listened from a table off to the side, Vance promised a "high-visibility presence in Jackson neighborhoods."

"We all could probably agree that that is the most effective tool in combatting crime," the chief added.

The police leaders promised massive enforcement, including stops for quality-of-life violations, which are typically low-level crimes that residents don't appreciate. The violations can also function as a useful gateway excuse, if controversial nationally, to search for a weapon or a warrant.

Vance and Mason are right. Side-by-Side is a classic strategy of police departments: Get several agencies—city, county, maybe state and federal—to work together to show an anxious public that they're out there making cities safer, or trying to.

Such operations can bring big arrests; as they make stops and check warrants, officers might catch someone wanted for a serious crime and toss him into "Mason's Inn," which the sheriff calls the Hinds County Detention Center in Raymond that his team now runs. The collaboration might make a big drug bust. And with any luck, their very presence, with many blue lights flashing and lots of questioning of possible suspects, will make trigger-happy criminals think twice, at least for the moment.

Or, research shows, all those blue lights and men with their hands up, although long considered policing 101, may create conditions that breed more crime.

A Half-Cocked 'Ceasefire'

The blue-and-gold "traveling trophy" stands maybe 4 feet tall and moves around to different precincts, honoring the commander and his officers who have seen the most dramatic drops in crime.

When Chief Lee Vance presented Precinct 2 Commander Jarratt Taylor with the award at the April 7, 2016, COMSTAT meeting, it came after a busy year, especially in Beats 7 and 10. In 2015, those two beats had seen a combined three murders, 51 armed robberies, 13 rapes and nine carjackings, in addition to high property crimes.

Beat 10 spans an area of west Jackson with West Capitol Street to the north, Ellis Avenue to the east, St. Charles Street to the south, out to the Clinton city limits. Beat 7 contains the Addition just south of JSU.

"He's coming up with strategies, motivating his people to do what they're supposed to do—that is prevent crime through visibility, arrest individuals responsible for committing crimes through quick response," Vance told me in his SUV about Taylor.

"We're not here just to maintain the status quo; we want to improve the crime picture in this city," said Vance, former commander of Precinct 2 who had won the trophy, a practice started by former Chief Robert Moore to boost morale, several times.

In 2015, Taylor helped execute a massive enforcement effort called Metro Area Crime Elimination, or MACE for short, promised to be a local version of the national Operation Ceasefire model. MACE drew officers from JPD, Hinds County and federal agencies to do massive sweeps of the area, similar to Side-by-Side now, except the latest effort, so far, involves the two local agencies.

The previous sheriff, Tyrone Lewis, instigated MACE, although Vance remembers going up to Cincinnati, Ohio, a couple of years back to learn more about the promising concept before he was chief.

"Operation Ceasefire was instituted in Boston, Chicago, Cincinnati, and Indianapolis, and these cities achieved reductions in gun homicide of 25 to over 60 percent," the California U.S. Attorneys website reports.

In Jackson, MACE targeted Beat 10 and then moved to Beat 7 in 2015, flooding those areas with police officers, resulting in many arrests for everything from quality-of-life violations to drug crimes.

"They came eight weeks straight every day for like four hours," Ray McChristian, the 19-year-old "Undivided" member, said about the operation last summer.

Vance said the "busy beat" needed attention. "The idea was to saturate it, root out the crime element. The crime over there was just about eliminated through all that saturation," he said in his SUV.

MACE was great while it lasted, police say. "It was a success," Commander Taylor said after an April COMSTAT meeting.

But here's the rub: Jackson didn't come close to doing MACE correctly, leaving off vital components that are core to the national, research-based Operation Ceasefire model, and cherry-picking the enforcement parts that people in the metro have long expected them to do, regardless of the outcome. In Jackson, the partners only did what Vance called the "enforcement piece" and didn't get around to the other prongs that the strategy's designers believe can actually interrupt gun violence in a community over the long term so young men don't end up in jail.

"I think the enforcement piece went well," Vance told me, "but the other administrative issues, so to speak, never really got established and up and running as well as the enforcement piece. ... The other parts of it were not fully implemented. It got stuck." Funding never came for the "research piece" or services, and then the sheriff's office turned over, and MACE "dwindled," he said.

Young men deemed to be at highest risk of shooting someone in the 2nd Precinct—the ones often dismissed as "thugs"—don't remember being summonsed to appear in a room where they would sit encircled by local law enforcement, FBI, the district attorney, the U.S. attorney, ATF and the Drug Enforcement administration, who would threaten to send them away to federal prison in another state if anyone in their gang or group committed gun violence. They didn't listen to a "Voice of Pain," a mother who had lost a son to gun violence who told her story to appeal to their "moral" sense as their family members sat in another room watching the drama play out on a big screen. They weren't then offered help with jobs, getting their GED or connecting with mental-health services from local social-service providers, or told that the people surrounding them believed in them, valued their lives and didn't want to see them go to jail. But they should have been.

This integrated strategy is at the core of the Operation Ceasefire model—a form of "targeted deterrence." The carrot-stick approach is carefully designed to reach men believed to be on the cusp of committing gun violence, let them know the consequences and help them fulfill their needs, thus finding a way to maybe change their trajectory into something more positive. At the very least, maybe they won't shoot or get shot.

It is not massive enforcement and flashing blue lights, even if that's what local residents think they need to see and police are used to providing.

The requirements of an effective Ceasefire clone seemed lost in translation locally. Mason explained at the 2nd Precinct on April 15 that he is getting a grant from the attorney general's office to do MACE again, except this time, he said, it would focus on "strict crime prevention." What does he mean? "It's mainly going to be used in our community-services division."

Those services, Mason said, will likely include elderly resources, paying for neighborhood-watch signs, anti-drug programs and reading programs—none of the services likely to stop young men who already have itchy trigger fingers combined with long-time trauma.

Mason also included regimented boot camps on his list—which could be used with the men Ceasefire is supposed to interrupt, even as it might make crime researchers cringe. But none of those things belongs in an Operation Ceasefire strategy, where the services offered must directly benefit young men like Zeakyy and his friends, who need jobs, GEDs and a chance to reboot.

'Soaked in Drama and PTSD'

In many ways, Operation Ceasefire started in a church in 1992.

Boston, Mass., was four years into the crack epidemic that nearly destroyed urban communities by the time the Morning Star Baptist Church became the site of a bloody gang retaliation for a drive-by shooting by teenagers. Gang members crashed a church service in Roxbury, the black neighborhood where teenage dropout Malcolm X first learned the street hustling that would send him to jail. The gang members came to church with guns and knives to attack rivals who had killed one of their own.

The incident became the kind of devastating wake-up call that another attack in a South Carolina church two decades later would be for the nation. In Boston's case, it telegraphed that the bloody gang retaliation cycle needed to stop.

In 1995, freelance writer David Kennedy, a white man who grew up in a Detroit suburb, was hired to research urban crime on the nation's urban streets with police as well as members of gangs and drug crews, for Harvard's Kennedy School of Government. What he and his teammates ultimately learned would profoundly push back on the myths about young criminals that were dominating media, the halls of government and even public policy: that troubled young men of color were remorseless, immoral "super-predators" who were multiplying.

By 2000, there would be 30,000 more boys age 14 to 17 becoming "high rate, repeat offenders," President George H.W. Bush's drug czar, William Bennett, and others warned in their book "Body Count: Moral Poverty and How to Win America's War Against Crime and Drugs" (Simon & Schuster, 1996). To bolster their argument, the men quoted James Q. Wilson, who co-authored the "Broken Windows" crime strategy along with George Kelling.

"Be ready," Wilson warned about the supposed "30,000 more young muggers, killers and thieves than we have now." The only way they could be stopped, those men argued, was through massive policing, even for minor crimes. They supported mass incarceration to get them off the streets.

That racist prediction was dramatically wrong. "Their argument was completely circular and almost entirely without evidence: Crime was caused by bad behavior, crime was horribly worse, therefore black kids' characters must be horribly worse, therefore black kids' bad character explained the crime," Kennedy wrote, attacking their logic, in his book, "Don't Shoot: One Man, A Street Fellowship and the End of Violence in Inner-City America" (Bloomsbury, 2011).

Instead, Kennedy hit the streets and learned that the young men who were driving a lot of street violence in cities from Boston, to Los Angeles, to Jackson were war-torn human beings who just might make a different decision if given the opportunity and motivation, especially if they also had access to the services, education and jobs that could interrupt the abusive cycle. The homicide rate then for black kids in Boston was 1,539 per 100,000 opposed to the national average of about 10 per 100,000.

"Those folks are always getting victimized at astronomical rates," Kennedy told me in his office at New York's John Jay College of Criminal Justice in December. "The people we normally think of as offenders are the most victimized population. ... The overlap of offending and victimization is always there."

That is, young people like the ones Zeakyy describes sitting in Sheppard Brothers Park, who as children have witnessed repeated violence and been punched in the belly by cops, are immersed in group dynamics that keep them bouncing back and forth between fear and bravado that can, in turn, get them killed or lead them to pull the trigger, often over a beef with a young person in a similar situation or just in an act of self-defense.

"This was a horrendously dangerous way to live," Kennedy wrote of the gang members he first got to know. "They were soaked in drama and PTSD," he added.

The young people didn't believe they had a way out, partially because it wasn't modeled for them and also because they believed it had always been this way, especially having come of age during the devastating crack era with little connection to the world outside their blocks. And they came up in neighborhoods with traditionally adversarial relationships with police officers who often only saw them as thugs, or even those hopeless super-predators that Bush's drug czar warned the nation had to be locked up.

Today, in 2016, many young men of color still believe they have no other options, that they are likely to die, that they need guns just to stay alive, as Zeakyy eerily described.

Kennedy also found that the young men, including the ones who had committed heinous crimes, didn't like their reality, even if they felt like they were trapped in it or that they had to live out the perceptions about them. He believed they might make choices to leave that life, if those options were available and provided to others in their gang and even opposing gangs, so they could "save face" and feel safe if they made a different decision. They often didn't know what the real legal ramifications of their group actions could bring, including federal prison a state or two away from their families.

Perhaps most importantly, their numbers turned out to be exactly opposite of the super-predator myth: The ones likely to shoot somebody were few in numbers and drove most of the violent crime, which is still true today. In fact, Kennedy found then (and still finds) that less than one-half of 1 percent of people in America's most dangerous areas are committing violent crime.

Here in Jackson, the police chief believes that 10 percent of the population is committing the worst crimes—a number that could turn out even lower if the granular data collection Kennedy pushes is embraced. Once the predicted shooters, or groups, are targeted, Kennedy's vision for Operation Ceasefire, which grew out of his original Boston Gun Project, is supposed to happen.

And it's not massive enforcement and sweeps; it's personal and targeted, designed to avoid getting the wrong people caught up in the police net. Once police identify those at risk of shooting—a process Kennedy describes in detail in his book—trained officers visit their homes, talk to them and their families, and deliver a letter telling them they must attend a "call-in." (Then called "forums," the first one occurred in Boston 20 years ago on May 15, 1996.)

‘Police vs. Black’: Bridging the ‘Racialized Gulf’

The divide between police and black communities is about more than white cops.

The young men sit in the middle of the room at the call-ins, surrounded by "moral authority" folks from the legal system, clergy, their communities and nonprofits who, as described above, threaten, cajole, shock and offer to help them, even as the young men themselves aren't allowed to talk until the refreshments after the theatrics end. The most compelling threat, Kennedy believes, is telling fearful young men that if one member of their gang or group commits gun violence, the feds will arrest them all and send them far away from home.

"We told them what it would take to make us go away," Kennedy wrote.

A concept called "pulling levers" is vital to Ceasefire: The idea is that the combination of local and federal criminal-justice players—from cops to prosecutors—can fashion a menu of ways to scare the young men straight. They might threaten a RICO organized-crime conviction, beefed-up paroles (with meetings in the precinct) or constant visits by police—whatever it takes to get the would-be shooters' attention.

A key threat is the promise to arrest the entire gang if one pulls the trigger—a component that irks Ceasefire opponents like violence interrupter and former gang member Shanduke McPhatter in Brooklyn, N.Y.

"What if I don't care if you're going to jail?" McPhatter said of fellow gang members. "What if I don't care if you take them, too? That's not going to stop me. Police threats are common, everyday occurrences for somebody who lives in the streets."

Still, Kennedy points to repeated success stories, starting with the original Boston Gun Project that became known as the "Boston Miracle" because gang violence fell dramatically while it was underway.

To work, Kennedy warns, Operation Ceasefire efforts must be well-oiled, systematic, collaborative affairs where all pieces of the puzzle are in place and monitored well. He believes most communities have most of what they need to pull it off, if they will align their resources right. "Never write a check you can't cash," he wrote in his book.

Cities like Jackson need to get organized and ask for help. "Any city has the tools it needs to do this work, for all practical purposes. But you need to know how to take what you've got and rearrange it to do this," he said. The information is in the public domain without branding or copyrights. Still, cities that try it without help from Ceasefire experts to "map it onto their own situation" often fail, making predictable mistakes.

The need for precision, of course, can also be Operation Ceasefire's downfall. A county like Hinds might just ignore major components, blaming the lack of resources, and another city might have personality conflicts or lose the will to keep it going, which eventually happened in Boston.

It's one thing to reduce violence, that is, and it is another to find the will, and the resources, to sustain the reduction.

That Vicious Policing Cycle

Still, the sustainability challenge is not even the main thing for Kennedy's loudest critics; it's the "pulling levers" aspect of Operation Ceasefire, or more accurately, who is threatening to pull them, that draws the harshest criticism of the model. It is the involvement of law enforcement that is often the deal killer for those most worried about the school-to-prison trajectory that many young people are launched on very young, such as with Zeakyy's fearful fourth-grade stay in Henley-Young.

Critics use the same research Kennedy relies on about how over-policing leads to more crime to argue that the core enforcement component of Operation Ceasefire does little to truly interrupt the cycles of despair that lead to crime in many of the nation's poor, black communities.

Brooklyn College sociology professor Alex Vitale is a critic of over-policing in general and, specifically, Operation Ceasefire, which he calls another version of a "punitive mindset." He points to his city's model that launched in 2014. "New York's Ceasefire is all stick and no carrot," he said last year. "Kids get a phone number to call to find out about services that exist. ... It's not particularly effective. It's a referral to nowhere."

Operation Ceasefire, Vitale said, "fits with a broader, neo-conservative world view; people are just economic creations and respond rationally to inputs. Root causes are a messy area (that) can't be quantified. (Ceasefire) doesn't take into consideration that people can be emotional and irrational."

A 2007 Justice Policy Institute study, "Gang Wars: The Failure of Enforcement Tactics and the Need for Effective Public Safety Strategies," shredded Operation Ceasefire, citing research that questioned many of its outcomes, its sustainability and even its core beliefs about how gang members responded to call-ins in some cities. "Probationers who participated in lever-pulling meetings were as likely as their counterparts to commit new crimes," the report found, and less likely to report "positive life changes."

The report also warned that law enforcement will always be the loudest, most controlling voice in a room supposedly "balanced" with service providers.

Sheila Bedi, a Northwestern University law professor who worked with the Southern Poverty Law Center in Mississippi to reform Mississippi's juvenile-justice system, agrees that the police can't deliver real juvenile crime prevention. "My bottom line is that as long as the intervention is within a police department, it is going to fail as a way to stop violence," she said last week.

"That's been proven over and over and over again. Police have one tool: the ability to arrest." In order for police to learn to truly prevent crime, Bedi said, "a culture shift would have to happen that (would) be so tremendous that it's not going to happen."

Gary Slutkin, the University of Illinois epidemiologist behind the Cure Violence model of training and paying former gang members to interrupt violence without police involvement, rejects the premise that either the threat of punishment, or acting on that threat, brings real prevention to a community. "The lockup solutions are not the solutions. They're not," he said in April.

"Behavior is not primarily formed by punishment," he said. "It's not maintained by fear of punishment. Those are old ideas."

Slutkin said the entire country is trying to figure out how to reduce prison populations and save the costs. "The easiest way to save money is to keep people out, not to put people in," he said. "Public-health methods keep people out because the event doesn't happen." Thus, the need is to "reach the hearts and to reach people" to keep the violent event from occurring, not threaten young people with federal imprisonment if a friend pulls a trigger.

Besides, the critics and the young people in the Washington Addition say, the targeted young men already live under constant threat. Another one won't necessarily stop the violence, or change the desperate conditions that lead them to desperate choices.

The Man of the House

Kvng Zeakyy's older brother may be locked up now—after committing armed robbery, home invasion, stuff like that, the young rapper said in the park in April. But his brother did try to have a good influence on him, teaching him to protect his mother, how to ride a bike and to "be the man of the house" when he was away. "He taught me good things, and more bad things," Zeakyy says, keeping one eye on his watch.

Why did his brother take guns and rob people? "Same reason I sold dope. He had his own way of hustling," Zeakyy said.

"He had a negative way of hustling. I have a negative way of hustling, but my negative way of hustling is the more positive way you can hustle in the streets."

The 17-year-old then explained his rationale for his own choice of hustle. His preferred approach—selling drugs, for instance—was giving people what they wanted. And he needed the money to eat and help his family.

But his brother's more dangerous hustle crossed Zeakyy's line: "His negative way of hustling is one of the worst (ways) you can hustle in the streets ... look at him as the bad guy in the streets."

"The police look at everybody as the bad guy in the streets," Zeakyy said, but many of them are just trying to get by and stay alive; they're living the struggle the only way they know how and hoping they don't get shot along the way. Then they commit a crime and, "Boom! They in jail doing time, 30, 40 years because nobody ever told them that ain't what you gotta do. You should stay in school and get a job, little brother, and I'll help you."

The lack of jobs, and training for them and transportation to get to them, really is the crux of the issue, many violence experts say. That includes Operation Ceasefire adherents who don't see policing going away, but want positive efforts added to it.

"We say very clearly, 'We want you alive, safe and out of prison," NYPD Deputy Commissioner of Collaborative Policing Susan Herman told me last May in One Police Plaza in New York. Herman's husband, Jeremy Travis, supported early Operation Ceasefire research and is now president of John Jay College where Kennedy teaches (and that awarded a fellowship for this reporting, but has not influenced it). Herman helped bring Ceasefire to New York in 2014 and believes in it passionately as a way to collaborate with the community rather than always bringing one-sided enforcement.

"We say very clearly what the consequences will be of continued violence, and we offer very real practical assistance for big problems and small problems that just get in the way of people being successful," she said. (Herman, incidentally, also convinced NYPD Commissioner Bill Bratton to reduce the number of arrests for low-level offenses, including pot possession, in New York.)

Alex Vitale looks at crime prevention differently—without police at its center.

Vitale describes his alternative to policing, including Operation Ceasefire, calling it his "model neighborhood": "I would set a massive youth job subsidy program, subsidize private-sector jobs, provide kids with public-sector jobs, jobs-on-demand. Then try to help young people find a job they can actually do, bring them up to speed, so they can actually do it, etc."

The JFP's 'Preventing Violence' Series

A full archive of the JFP's "Preventing Violence" series, supported by grants from the Solutions Journalism Network. Photo of Zeakyy Harrington by Imani Khayyam.

Sure, such a model would cost money, as does a solid Cure Violence model—Slutkin says an effective one starts at about a $350,000 investment in order to train and give jobs to violence interrupters—but such investments would pay off if taxpayers were willing to get serious about violence prevention that doesn't involve prisons and hiring more cops, Vitale said. And more people would stay alive and out of prison.

"As soon as a bullet hits a person, you've got an average of $400,000 costs," Slutkin said, "sometimes a million or more." (A caution, though, in cities including Chicago and New Orleans, Cure Violence programs are called "Ceasefire," even though they do not involve law enforcement. And New Orleans and New York, among others, do both Cure Violence and Operation Ceasefire models. In New Orleans, the Cure Violence program is called Ceasefire, and the Operation Ceasefire program is called the Group Violence Reduction Strategy)

But are Jackson and Mississippi ready to invest in that level of violence prevention, even if it would pay for itself? A crime-prevention program that doesn't have law enforcement in a prominent position could stand little chance of support from those who prefer paying for prison beds to adequately funding education and the health care of children who don't admit to drug dealing and breaking into schools.

Thus, the appeal of the "balanced" Operation Ceasefire to many. When done correctly and despite its downsides, it can function as a compromise of sorts that brings police and the community together in an about-face on blanket enforcement and the rounding up of would-be super-predators.

As for Zeakyy, he had to cut the interview short when he saw his mentor, John Knight, riding up to the park on a bicycle with a crowd of young men on bikes following closely behind. Zeakyy shoulder-bumped photographer Imani Khayyam and headed toward the next picnic tables over where the "Undivided" meeting was about to get underway. He was on time.

Join JFP Editor-in-Chief Donna Ladd and JPD Chief Lee Vance Monday, May 9, at Millsaps College at 6 p.m. for her inaugural "One-on-One" series with newsmakers and leaders. Free, but please RSVP here, where you can find all event details.

This is the second part of a "Preventing Violence" reporting project, supported by a John Jay College of Criminal Justice fellowship and a grant from the Solutions Journalism Network. Visit jfp.ms/preventingviolence for the full series. Please see Operation Ceasefire and Cure Violence. Additional reporting in New York by Donna Airoldi.

Corrections: The original print edition listed WJTV as the source of the video report about Chief Vance at the scene of the Fontaine Avenue murders. The above story is corrected and links to the WLBT video. Also, the original story stated that Dr. Gary Slutkin is with the University of Chicago, but it is the University of Illinois, and has been corrected above.

More like this story

More stories by this author

- EDITOR'S NOTE: 19 Years of Love, Hope, Miss S, Dr. S and Never, Ever Giving Up

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Systemic Racism Created Jackson’s Violence; More Policing Cannot Stop It

- Rest in Peace, Ronni Mott: Your Journalism Saved Lives. This I Know.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Rest Well, Gov. Winter. We Will Keep Your Fire Burning.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Truth and Journalism on the Front Lines of COVID-19

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.