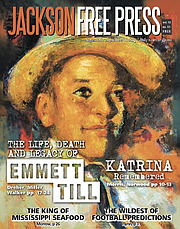

Donham's confession, far from providing a national scapegoat for the murder of Emmett Till, emphasizes that violence, untamed and unpunished, aimed at African Americans is not a modern story but has a long legacy in America. Photo courtesy Simeon Wright

When the news broke that Carolyn Bryant Donham—the white woman infamously at the center of the murder of Emmett Till—admitted to lying in court during the 1955 trial of her husband, Roy Bryant, and his half-brother, J.W. Milam, public outrage exploded. Historian Timothy Tyson revealed the news in advance of his new book, "The Blood of Emmett Till." Tyson is the only historian known to have interviewed Donham, and having sat down with her in 2007, he claims that Donham, still alive, is remorseful for her role in the tragedy and that she thinks of Mamie Till Mobley, Emmett Till's mother, with a sense of regret.

In the public's eye, those drastically inadequate and seemingly insincere revelations added fuel to the fire to condemn Donham and bring her to long-awaited justice, which was denied since her husband and brother-in-law were acquitted. Much of the public indignation, anguish and hostility, particularly in black communities, must be understood in the context of well-publicized, often officially condoned and systematically perpetrated brutality against black bodies.

For many white Americans, the fact that Donham outed herself is a shock. Her admission has given these people stones to throw for her guilt in Till's murder. In turn, they will soon feel inclined to shut the door on this ugly chapter in American history and claim that it is all behind us.

But the condemnation from African Americans is not born from surprise that Donham had perjured herself. The news that she had lied did not shock African Americans or those of us who work with black communities. We knew she was going to lie before she took the stand in 1955.

Mose Wright, Till's uncle, knew she was lying when he stood up in court and identified Bryant and Milam as the men who abducted his nephew. Mamie Till Mobley knew Donham was lying as she sat in the segregated courthouse in Sumner, where a billboard declared that it was "A Good Place to Raise a Boy" without any hint of cruel irony. Wheeler Parker, Till's cousin, who was there during the whistling incident, knew that Donham was lying and has told anyone who would listen for the past 60 years. Bryant and Milam themselves admitted it when they confessed to kidnapping and murdering Till for a 1956 Look magazine article. Historian Devery Anderson, whose 2015 book "Emmett Till: The Murder That Shocked the World" is the most definitive account so far, told us as much.

Instead, Donham's confession, far from providing a national scapegoat for the murder of Emmett Till, emphasizes that violence, untamed and unpunished, aimed at African Americans is not a modern story but has a long legacy in America. The assault against African Americans has been at the heart of the power structure in this country since the days of the Founding Fathers and their commitment to the institution of slavery. If anything, the renewed interest in Till and in Donham, who should go to prison if her role is proven to be prosecutable today, reminds us that the Civil Rights Movement was not that long ago and that the struggle continues.

If anything "good" comes from this news, it may be the inspiration of a new generation of activists, much like Till inspired six decades ago. It will not be some kind of satisfactory conclusion to the Till saga or Mississippi's racist history. Rather, it will be a recommitment to the work of black empowerment and racial reconciliation, which can allow us to use our past to shape our present. My son, who is 2 years old and named Emmett for the boy who inspired my own activism, has the chance to inherit that legacy.

Robert Luckett is the director of the Margaret Walker Center and a history professor at Jackson State University.

Read more JFP stories on Emmett Till at jfp.ms/till.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.