Will Selman, a biology professor at Millsaps College, studies the Ringed Sawback turtle, which can only be found in the Pearl River. Photo by Imani Khayyam.

Trash hangs from tree branches, swaying in the breeze, a few weeks after the Pearl River crested past moderate flooding levels. During the storming in the last part of March, the river crested above 33 feet, National Weather Service data show. The Pearl was close to level with the Lakeland Drive overpass that connects Jackson to Flowood.

Now, the water has gone down dramatically, leaving brown water lines on vegetation due to sediment and dirt and trash in tree branches or strewn along the recently settled banks.

In Jackson, the Pearl River runs right next to the Mississippi Coliseum, Interstate 55 and numerous businesses built on the floodplain. Tributaries—creeks that run off the river—create flooding risks for residents. Town, Belhaven and Eubanks Creeks put structures in downtown Jackson, Belhaven and Fondren in 100-year floodplains, maps from FEMA show, meaning a major flood is expected once every 100 years.

The largest to date was in 1979.

Unpredictable Floodplains

People like to settle near rivers due to their need for water, good soil and potential food sources a river can provide, not to mention recreation.

Still, it is important to remember that flooding is a natural part of a life of a river, Ben Emanuel of the American Rivers Association says. The largest flooding event in Jackson's history was the Easter flood of 1979 when water levels crested at 43 feet. Businesses in downtown Jackson flooded, and old pictures show the Coliseum appearing to float. This is all predictable, however.

"When we get catastrophic flooding is when we've over-developed in the floodplain," Emanuel, who directs ARA's clean water supply program, told the Jackson Free Press.

This is the case in Jackson as well as other parts of the South, and sometimes even 100-year flood maps cannot predict catastrophic events. The August 2016 floods in Louisiana affected more than 55,000 homes, the National Weather Service reported, and 80 percent of those homes were outside the 100-year floodplain. Emanuel said 500- and 100-year floods are becoming more intense in some places, a vital fact to keep this in mind when building new infrastructure.

"Any water infrastructure project nowadays needs to be taking into consideration what changing rainfall patterns that may or may not be a part of climate change," Emanuel said.

"River patterns and weather patterns are changing, which in turn change the modeling."

Nationally, there is a flood-control movement toward using natural infrastructure and removing both dams and levees, some of which are old infrastructure that stop working, are too costly to keep up or break with too much water.

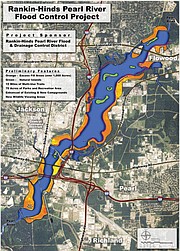

In Jackson, about 11 miles below the Ross Barnett Reservoir and most of Lefleur's Bluff State Park along the Pearl, a weir dams up water so the City of Jackson can take up enough water to serve the city at its treatment plant. The Rankin-Hinds Pearl River Flood Control District, long called the Levee Board, has proposed to remove that weir and flood out a portion of the wetlands around the state park as well as portions of land along both sides of the Pearl between Lakeland Drive and Interstate 20.

The idea is to create a larger body of water, referred to as a "lake," to help with flood control and build a new weir downstream, a few miles south of Interstate 20 on the Pearl. The "One Lake" plan also promises lucrative development, waterfront property and recreation.

Turtles Aren't Stupid

Will Selman, a biology professor at Millsaps College, studies reptiles, specifically water-going turtles. The Ringed Sawback turtle, which he has researched extensively, is a species only found in the Pearl River and its tributaries. With co-author Robert Jones, Selman recently published results of a study that observed the Ringed Sawback and the Pearl Map Turtle species found in the Pearl River.

The long-term study concluded that populations of both turtle species are declining both north and south of the Ross Barnett Reservoir, which was constructed in the 1960s. This decline is due to several factors, Selman's paper concludes, from altered water flow and water quality to human disturbance. The turtles are acclimated to using a river environment for survival, food and reproductive purposes, and Selman said turtles are also acclimated to flooding.

"Instead of being flushed upstream or downstream ... they aren't stupid, they'll move to slower-moving water areas," Selman said. "They will move away from the channel to the flooded forest, so there's a lot less velocity."

Fish also use the wetlands as breeding grounds, Selman said. The value wetlands provide in terms of flood absorption potential, while not monetized, would probably equal millions of dollars per year to the city of Jackson, he said.

"Wetlands are like sponges and ... provide some really important what we call ecological services, so flood mitigation is one of the most important aspects of a wetland because it can absorb excess water and mitigate the flooding," Selman explained recently.

Turtles use the logs along the Pearl River's banks, called deadwood, to bask in the sun, hide from predators and eat. Turtles need sunlight to warm themselves, as well as heal and shed scoots from their shells. Turtles eat the organisms that grow on dead wood underwater, as well. Female turtles, especially, are visible along the Pearl during the springtime, as they soak up the sun to increase their body temperature. When they're warmer, turtles eat more and get more energy to produce eggs and nest in the summer, Selman said.

The female turtles use the sandy banks to lay their eggs and nest between late May and mid-July, research shows. Turtle survivorship in the first 10 years of life is very low—less than one turtle will likely survive each nest, Selman said. Females do not become fertile for about a decade or longer, so turtle survivorship relies on the little ones making it not just out of the nest but also out in the wild for at least a decade before getting the chance to repopulate.

"For turtle life history to work, the adults are the most important class of turtles because they're the ones who have made it through this arduous period of 10 to 15 years to get to reproductive maturity," Selman said.

What 'One Lake' Could Change

Keith Turner, the attorney representing the Levee Board's project, acknowledged that the project would change parts of the wetlands, flooding or moving them while maintaining their "jurisdictional waters" designation from the federal government. Part of the "Lake" plan is to excavate some existing wetlands, clearing a more direct and open path for water. The contractors would use the excavated dirt to build excess "fill areas" to line the sides of the new body of water, the project map shows, but Turner is confident the same wildlife will remain in the project area.

"They're not leaving the project area because they'll have the same habitats that they will be able to function in, with the islands and the other areas all around ... it's all connected," Turner said.

Turner said that while wetlands have flood storage capacity, it is not enough along the Pearl River because in both Rankin and Hinds Counties, communities are built right up against the river.

"The wetlands don't provide a benefit in that sense when your flood water is up into the trees above the roots, all those trees are obstacles for the water to flow," Turner said. "All of it creates turbulence and resistance for the water moving through, so there's not a flood-reduction benefit in that case."

The "One Lake" project proposes a few islands that would go untouched by excavation, hypothetically high elevation points to serve as wildlife environments.

"We will have some areas that we will leave that are very high for environmental benefits for the animals to be able to have a place ...," Turner said.

The Levee Board and its contractors are working with state employees at the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Turner said, as well as with federal employees, on the environmental aspects of the project. The proposed project widens the Pearl significantly into a lake-like environment, however, and Selman said he believes some turtles would stay and some would leave if the project comes to pass. There is no before-after data available to see what the fate of a turtle species would be as a result of a project like this, he said.

"You can almost guarantee all the river-adapted organisms will either move upstream or downstream, or they'll become locally extinct, and they'll be replaced by things that are adapted to a lake setting," Selman said.

Turtle lifespans, which range from 60 up to even 80 years, make it difficult for researchers to track or predict in any timely manner whether or not a population is viable, or is producing young turtles to replace the old ones dying out.

The "One Lake" project's stated main goal is flood control. Dallas Quinn, who represents the Pearl River Vision Foundation, which is developing the plan, said the project's main flood-control method is conveyance. That would mean moving water through a larger volume area at a slower pace, using the weir to control flow, without impacting any downstream communities. The dredging—digging out parts of the Pearl River to make it deeper in certain parts—will also create more capacity for the river during flood conditions, Quinn said.

How those two goals will better serve flood control remains to be unveiled, and in the coming months, the Levee Board plans to release a feasibility study for the project to address that question. The board has hired a contractor to conduct the study on the project, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is assisting the researchers.

The Levee Board is also completing a draft of a voluminous environmental impact statement for the project, a report that federal agencies would normally conduct if a federal action "is determined to significantly affect the quality of human environment," the Environmental Protection Agency website says.

Greg Raimondo, public-affairs chief at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in Vicksburg, said no actions are pending in terms of regulatory permits for the project. Turner said they expect the feasibility and the environmental studies to come out by late May or June and be available for public comment.

Correction: An earlier version of this article attributed a quote about river-adapted organisms to Keith Turner, it was said by Will Selman. That attribution has been corrected. We apologize for the confusion. This is the first in a new series of new stories on the proposed "One Lake" plan. Read past coverage at jfp.ms/pearlriver. Email reporter Arielle Dreher at [email protected].

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus