Hinds County Senior Circuit Court Judge Tomie Green says Hinds County has had to piecemeal a sort of mental-health court together because the wait at the state hospital for evaluations is so long. Photo by Imani Khayyam.

JACKSON — Tomie Green remembers the young man who convinced her that mental-health treatment worked. The Hinds County senior circuit judge recalls him on the stand for a hearing, struggling to answer questions from both Green and attorneys.

"His answers to my questions were inappropriate—he looked like he was glazed over," Green recalled.

The teenager had bipolar disorder as well as some symptoms of psychosis, Green said, but he had committed a serious crime. She made a choice to order him to treatment—not prison—that day.

She chose electronic monitoring to ensure he stayed in treatment, and his parents took him to Louisiana to get the intensive therapy and care he needed. Green received regular reports on his progress and said he was completely transformed three months later when he walked into her courtroom.

"I asked him if he felt any different, and that's what he said, 'It was like coming to life again,'" Green told the Jackson Free Press. "For me it was like the day he left, he was inside a dead person, and the young vibrant articulate young person who walked back (in after) treatment was a whole other individual."

To this day, Green cannot remember his crime or even how the case was resolved—but she does remember one thing.

"The reason I remember him is because it made me believe in the system of treatment for people with mental health," the judge said.

The Court's Few Options

Judges in Mississippi have few options when sentencing men and women who need mental-health care but have also committed a crime.

The first hurdle is to declare a person "insane" by state law standards, or not competent to stand trial. A private, forensic non-treating psychiatrist must evaluate a person and declare him or her incompetent to stand trial, Green said.

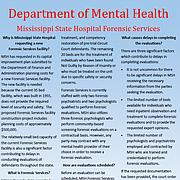

Mississippi State Hospital psychiatrists can conduct the evaluations at no cost to the county, but there are only 35 beds for all criminally charged people in the hospital at Whitfield. Fifteen of those beds are for inpatient evaluation, information from the Department of Mental Health shows.

As a result, Green said people were staying in jail for years because the state hospital did not have room for them and the county did not have the funds to pay a psychiatrist to evaluate individuals in-house. If and when people are declared incompetent to stand trial, judges can commit them to Whitfield—if there's space.

In Hinds County, in recent years, Hinds County Circuit Court judges contract with a few private psychiatrists to conduct evaluations, so those with mental-health conditions do not sit in jail for as long as they did in previous years.

"That became our goal: to get them tested as soon as possible after they were in the jail, then I'd know if he's incompetent in a few months," Green said. "(Then) I'd know we can't try him, and we need to look at some alternatives."

Using private psychiatrists is faster, but it also costs the county money, Green said, and while the Hinds County Board of Supervisors has supported the circuit court's efforts, the makeshift drug court is the best Green and her colleagues can do for now.

"In Mississippi and in Hinds County, people with mental illness are still lingering in our jails much longer than all of the other defendants," Green said.

Finding Solutions?

Mississippi State Hospital has 384 beds for mental health and substance-abuse treatment, but only 35 of those beds are in the forensic unit for Mississippians who have been criminally charged.

Adam Moore, communications director at the Department of Mental Health, said the wait list for those 35 spots is from nine to eleven months. He said one of the problems statewide for evaluations is the lack of trained providers credentialed to conduct mental-health evaluations for the court.

DMH also requested funds to build a new forensic service facility in recent years. In fiscal-year 2016, DMH conducted 210 pre-trial evaluations at the state hospital and admitted 37 people for post-trial "competency restorations." DMH received a budget cut in the current fiscal year, however.

All spots at the state hospital are reserved for judges to commit men and women for treatment. The large majority of the beds at Whitfield are for civil commitments to the hospital, and sometimes, Judge Green said, the court is able to transfer an initially criminal case to a civil one, if a person is deemed incompetent to stand trial and is not considered a public-safety threat.

Beyond committing a person civilly, which requires some maneuvering among several lawyers and parties involved, Green said her court partners with the community mental-health center, Hinds Behavioral Health Services, for additional resources.

The community mental-health center can assist the court in referring men and women to programs as well as assisting the court in getting funding. Green said she sees many people in need of mental-health care who are disconnected with their families come through the system, not wanted at home or charged with domestic violence if they try to go back home.

"They are the people who sleep in Smith Park or other places for the homeless," Judge Green said. "They find a bed any place they can, but they are also the people that the police see peeing on the street and bring them in for that."

The senior judge envisions a program that includes housing, maybe using one of the old hotels on Highway 80, she said. Those buildings have bedrooms upstairs and offices downstairs where social workers, psychiatrists and security can all be in the same location providing a system of care for people.

"They (could) have a place to live, and they have a place where their medicine can be dispensed, and right now we don't have that," she said. "And Hinds County is one of the places that needs it the most."

An Unfunded Mandate?

Recently, top Republican lawmakers started touting community-based services as the right mental-health approach, as the State faces a U.S. Department of Justice lawsuit for the over-institutionalization of the system. Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves and others praised the Legislature's passage of House Bill 1089 at the Neshoba County Fair this summer. The legislation established mental-health courts in six of the state's 22 circuits. Hinds County was not included in the list.

"I was disappointed when I looked, and I recognized that this has been at the forefront of Hinds County (Circuit Court) for at least 10 years, and they came out with a bill and nothing in it added Hinds County as a pilot program—that concerns me," Green said.

The bill does not provide a funding mechanism for the six mental-health court pilot programs in the state, and circuit courts will be forced to apply for grants on their own or ask their counties to help fund the programs.

In Jackson, Judge Green said her court is seeking a planning grant on its own to help the circuit court collect data to know who has been treated and how they have been treated based on her and her fellow judge's orders. Having this data, she said, would substantiate the court's need for additional funding and programming.

Still, she said, it's "disturbing" that the state did not include the capital city as a part of the pilot program.

"When you look at the other places, they may have some problems, but they certainly couldn't have the mental-health problem that Hinds County does with the number of people that come through our system," Judge Green said. "...So I'm praying that the pilot works and that it (receives) statewide funding, and a mental-health court is established."

Email state reporter Arielle Dreher at [email protected]. See more stories at jfp.ms/mentalhealth.

More like this story

- Man Held 11 Years Without Trial Will Go to Mental Facility

- Cops Learn to Help Mentally Ill Mississippians

- Lost in a Broken System: Why Detainees Spend Years in Hinds Jails Without Trial

- Mental Illness: Behind Bars and Beyond

- Mental Health Task Force Aims to Improve Services, Including for the Accused

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus