Margrit Wallace, chief academic officer of the student academic and behavioral support department at Jackson Public Schools, tracks suspension data and helps run rapid response teams to schools with high rates of suspension. Photo by Imani Khayyam.

JACKSON — Melissa* wants to study child development after she graduates next spring, maybe nursing, she says. The senior attends high school in Jackson Public Schools and says too many of her classmates get suspended. Even on the first day of school this month, she witnessed a classmate get suspended for not paying attention in class.

"The teacher told her to turn around, and she kept looking out the window," Melissa, who is black, told the Jackson Free Press. "(The teacher) called somebody on the intercom to come get her, and the principal came to the door, and she got suspended for looking out the window."

Melissa said the girl got two days of suspension out of school just like that. While Melissa works to be a good student, she was suspended near the end of the last school year. She and her friend got a hall pass from their teacher to return a book bag to a student in another grade, she says. They were returning to their classroom when a teacher saw them in the hallway.

"He just said three days. ... I was so mad," she said. "He wouldn't even let me explain myself to let him know why I was over there. ... We had a hall pass, but he told the principal that we didn't have no pass, and I feel like they should have investigated it a little more."

The teacher took Melissa and her friend straight to the principal's office. Melissa admits that she did mouth off. She said she didn't curse, but did talk back because she was frustrated that the teacher and the principal would not let her explain herself.

"I was being disrespectful because he wouldn't let me get my words out, and that made me mad," Melissa said last week. "He said that I was cutting class, but he didn't investigate. ... He didn't go to my teacher and ask , 'Did you give so-and-so a pass to do this?" she added.

It was near the end of the school day, anyway, but security guards had to go get Melissa's items from her classroom because she was not allowed to go back. She sat at home for three days watching television.

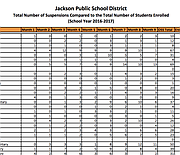

Melissa's suspension was one of the 8,412 out-of-school suspensions in Jackson Public Schools in the 2016-2017 school year, data from the district show.

The majority of those out-of-school suspensions occur in middle and high schools in the district. Some schools have much higher rates than others.

Interventions Instead?

Blackburn, Hardy, Peeples and Rowan Middle Schools have 100 percent or higher rates of suspensions, meaning their total number of suspensions is equal to or greater than the number of students enrolled there. (Rowan Middle School is now closed.) Lanier, Forest Hill and Wingfield High Schools have the highest rates of suspensions for high schools in the district.

Nationally, suspensions have decreased, but a December 2016 White House report, which the Trump administration has removed from the White House website, showed that 2.8 million students received out-of-school suspensions in the 2013-2014 school year. Suspension, the report says, can contribute to already-adverse outcomes for kids "in areas such as personal health, interactions with the criminal justice system and education."

"Reliance on exclusionary discipline has also contributed to the development of the school-to-prison pipeline," the December 2016 report says. "Students who are suspended from school have an increased likelihood to have contact with the criminal justice system and are more likely to face incarceration in their lifetime."

A 2011 study of Texas schoolchildren found that African American students and students with educational disabilities were disproportionately likely to be removed from the classroom for disciplinary reasons. Often those reasons are minor.

JPS administrators recognize that out-of-school suspension is not the way to change school climates district-wide, and Margrit Wallace, the JPS chief academic officer in the student academic and behavioral support department, is working to move the district towards restorative justice practices, which could eventually include dialogue circles in the classroom.

Wallace showed the school board suspension rates from throughout last school year, and her office tracks the data in order to make "rapid response" visits to those schools with the highest suspension rates.

Her department is working to implement other programs that address school-discipline practices and change school climates. Her office also actively works to apply for grants to pay for programs and teacher training.

One of these programs, called Tools for Life, comes with curriculum for teachers to integrate into their lessons that teach students how to interact socially, understand their emotions and take appropriate actions when addressing conflict. JPS is rolling out the program in all its elementary and middle-school classrooms. Half the district's elementary and middle schools got the training last school year, and this year, the rest of those schools will get training.

One part of the program encourages teachers to have a calming area in their classroom where a student can go to calm themselves down. Wallace said the calming area is a "self-selecting place," meaning it is not a punishment, and teachers can never make a student go there. Having a calming area is now a standard practice in all elementary and middle schools in JPS, and Wallace said the district is exploring how to bring the concept to high schools.

Wallace said she has seen Tools for Life work in real-life. She visited a first-grade classroom and saw a young boy use the calming area.

"I asked him, 'What are you doing?' And he said, 'Well, I found myself really getting tense,'" Wallace said. "Then I said, 'What did that tell you?' and he said, 'Well, that told me that I was getting angry, and I realized I needed to move away and do some problem solving."

Wallace said the goal is to create positive school environments for the students and the teachers alike.

"This is about helping the students to change their behavior—we're not punishing children—this is about teaching students appropriate behaviors and helping them have that safe space to develop those behaviors and having consequences for the choices they make that are aligned with that behavior," she said.

The district's goal is to move toward restorative-justice practices, like mediation and dialogue circles in the classroom, and programs like Tools for Life are a start. JPS received an almost $5-million grant from the National Institute of Justice to implement Tools for Life in fiscal-year 2015. Wallace said JPS is looking for funding for more restorative-justice grants.

"The main obstacle for us is funding," Wallace said. "The vision is there—it's getting the funding because the teachers need to be trained."

Beyond Tools for Life, the district has a few other planning grants run through partners that fund peer mediation and provides some teacher training. This summer, the school board approved changes in the district's code of conduct, which could help lower the district's high suspension rates.

Changing the Code

JPS' code of conduct in past years listed behaviors and consequences on a continuum, and often out-of-school suspension was the strictest punishment for behaviors from violating the dress code to being tardy. The new code of conduct, in effect for the present school year, changes this model. Now, behaviors exist on a progressive scale, with an outline of steps teachers must take—even before they get the principal involved for some of the violations. A student now cannot receive an out-of-school suspension for a first-time dress code or electronic-device violation, inappropriate behavior, being tardy or a bus disturbance. The new disciplinary plan lists a myriad of alternative actions teachers can take, from student conference, to a whole class meeting, to loss of privileges .

Wallace said the new code of conduct helps actually define some of the catch-all terms, like "insubordination" and "creating a disturbance" that data showed team school administrators were using.

"We've looked at the discipline referrals and decided what's happening most," she said. "We took things out that we thought were catch-all behaviors."

Teachers can still choose an in-school response, like in-school detention or in-school-suspension, for a student's behavior. Wallace said the new code of conduct, which community and school stakeholders gave input toward, focuses on ensuring that a teacher or principal's response to a student's behavior is aligned with that behavior. She said the new code emphasizes the preventive actions that teachers and principals can take and was modeled after what other successful school districts do.

Jeremy*, who is also black, graduated from Jackson State University's continuing education program with a GED after struggling in multiple JPS schools.

Before he dropped out, he had received several suspensions.

In an interview, Jeremy recalled kids getting suspended for any dress-code violation, from boys tying rubber bands around the ankles of their pants to girls wearing tight pants. One of his high-school principals called the Jackson Police Department on him once, which led to a suspension but no arrest.

Jeremy said his first JPS high school used in-school suspension, but he had never heard of in-school detention in real life, where students go sit in a classroom usually after school as a consequence of something they did wrong. "What is detention? That stuff is on movies. ... That's the only way I know what detention is," he told the Jackson Free Press. "When the kids sit in a room and have to do something? I watch it on movies and stuff."

Melissa, who attended a different high school for her first year and a half, said the discipline between the two high schools is very different. Her old high school, she said, had in-school detention, and a student had to do something really bad to get suspended. Students could bring their homework to in-school suspension there, she said. At her current high school, however, students have to work hard to get missed homework assignments from the time in out-of-school suspension.

Jeremy said it depended on the teacher. He would have friends get his schoolwork for him when he was suspended, but not all teachers would give it out.

"Some teachers will say, 'He's suspended; he's not supposed to be here; it's his fault he's suspended, so he'll get those zeros and learn next time,'" he said.

A Work in Progress

Wallace says she is excited about JPS moving in the direction of restorative justice. Tools for Life is implemented in the district's alternative school and the Henley Young Juvenile Detention Center, she said. JPS provided professional development for all principals before the new school year to get them up-to-date on the new code of conduct, and principals are expected to help teachers understand and interpret the new code of conduct with fairness and fidelity, she said.

Wallace emphasized that one of the keys to programs like Tools for Life and creating positive school climates is teachers understanding the need to have relationships with their students. In an accreditation visit from AdvancEd, officials emphasized one of their criteria for a school is that each student has an opportunity to build a healthy relationship with adults, Wallace said. After implementing Tools for Life in middle schools, some previously skeptical teachers expressed appreciation for the program.

She recalled one teacher who put it this way: "I realized I can't teach the children unless I have relationships with them. ... I thought my job was to be academic but now ... I look beyond that initial behavior to a cause."

*Students' names have been changed to protect their privacy.

Read about the school-to-prison pipeline at jfp.ms/preventingviolence. Email state reporter Arielle Dreher at [email protected].

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus