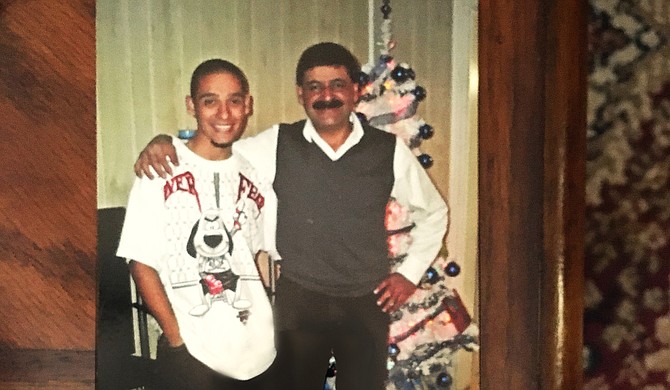

Immigration officers took a young woman’s brother (left) and father (right) from their home in Jackson on Wednesday, Feb. 15. Arielle Dreher/Photo of Family Photo

JACKSON — Daniela Vargas was asleep early on Feb. 15 when she felt her father kiss her goodbye, as he did every morning. It was around 6:30 or 7 a.m., a seemingly normal Wednesday morning—until it wasn't. Just a few minutes later, her father came back, waking her: "Dani, immigration is here!"

Panicked and sleepy, the 22-year-old didn't know what to do. By the time she got up and looked outside, her brother's truck was parked haphazardly up in their front yard, a sign something was not right. There were immigration officers in her father's room asking to see his passport. Vargas began translating; her father does not speak English.

The officers asked to see her I.D., which was out in her car. They escorted her to her car, and she told them she was a DACA student, and then before she knew it, they brought her father out of the house in handcuffs. When the officers kept questioning her about her status, Vargas got scared, went inside and locked all the doors. She still hadn't seen her brother, and she assumes he was already in one of the several ICE vehicles with tinted windows.

Vargas barricaded herself in her closet, knowing she couldn't run away. The agents were around the house, and eventually they came back inside. She still does not know how the immigration officers got into her house, but once they found her, they showed her a search warrant with her brother's name on it.

They were looking for weapons. Did they have any? Vargas knew about the gun. They had one for protection, she says. Her father got the gun only when they moved to Jackson last May because they didn't feel safe in the neighborhood, she said later. Immigration officials searched the house for the weapon. Vargas crouched in her bedroom, calling friends and her mother who lives out of state. She had no idea if the immigration officials would take her, too.

She later said it seemed like she got some sort of pass because she told them about the gun, which they eventually found. Around 1:30 p.m., several men, maybe seven, streamed out from the back of the house. They got into two sedans and two SUVs, and rolled out of the driveway.

Vargas burst out of the front door a few minutes later. A lawyer from the Mississippi Immigrants Rights Alliance and a gaggle of reporters greeted Vargas, who was clearly scared and seemed in a state of shock. Bill Chandler, the executive director of MIRA, said his organization was familiar with Vargas and her family, which is why they knew to be there.

Vargas had the search warrant ICE officials gave her, and her passport was on the entry-room table.

Safe for Now

Vargas is a tax-paying worker and former student on the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals plan, known as DACA, which the Department of Homeland Security back in 2012 during the Obama administration. The program allowed children of undocumented immigrants, who are technically undocumented themselves, to request deferred action on their removal from the country as well as become eligible to work in the country.

The young woman came to the United States when she was 7, and never returned to Argentina. The family settled in Morton, Miss., where Vargas graduated from high school. She applied and was granted DACA twice, and her current application for renewal is still in process.

With her father and brother gone, Vargas had no idea what she would do. The three of them lived in a house in west Jackson, where they moved in May from Morton, after her parents divorced, Vargas said. Her mother lives out of state.

Inside the house that day, Vargas' father's room was a mess with clothes bunched on the floor, a huge shelving unit pulled from the closet, clothes and other household items strewn across the floor.

"It's weird seeing his room like this, he is such a neat person," Vargas said, looking at the ICE officials' handiwork.

Old photos of the family, tacked onto a large vanity, looked down on the mess of her father's room, and afternoon light streamed in through blinds. Vargas' room, just a few paces from her father's, was neat. She had written a message on her vanity mirror to her mother, and she repeatedly told her friend on the phone to tell her mother that she loved her, thinking she would be taken away, too.

Vargas thought they would take her, and seemed both relieved and confused as to why they didn't on Feb. 15. She is still in the state, now represented by Abigail Peterson, with Elmore and Peterson attorneys.

No Word from Father, Brother

Vargas thinks ICE came to their house because of her brother Alan's past. She said a woman brought charges against him for kidnapping and rape years ago. Alan was sent to jail and then released when they figured out she was lying, Vargas said, and the girl who lied moved out of state.

"We never saw her again so because of that, the record was not wiped away," Vargas said. "But he wasn't guilty, so he got to walk and she left, and that's what follows him everywhere."

Alan's case in the U.S. District Court is sealed, so it is not clear whether or not officials used those charges to justify the search warrant. Vargas said her brother was not guilty of anything and that the woman had lied. Her brother framed houses and worked in construction.

Vargas said her father, who paints houses for a living, had no criminal history. He was on a U-Visa, which is for non-immigrants who are victims of crimes. Vargas said her father was harassed at a previous job, and was in his re-application for the visa. As a DACA recipient, Vargas is not eligible for scholarships or federal student aid for college, so most of her father's paycheck went toward her schooling, she said. She most recently studied journalism at the University of Southern Mississippi. She had to take this semester off because they couldn't keep up with the bills. She said she is considering teaching math and wants to go to Mississippi University for Women.

Mississippi has no official immigration detention facilities, so when ICE officials pick up Mississippians, they are eventually sent to a facility in Alabama or Louisiana, ICE spokesman Tom Byrd said. "(ICE) Fugitive Operations teams arrest criminal aliens and other individuals who are in violation of our nation's immigration laws," he wrote in an email to the Jackson Free Press.

"ICE conducts targeted immigration enforcement in compliance with federal law and agency policy. ICE does not conduct sweeps or raids that target aliens indiscriminately."

In a further interview, Byrd said all individuals in ICE custody are afforded due process, and they will go before an immigration judge to make their case. Byrd could not confirm where Alan or Daniel currently are due to privacy issues, he said. Sometimes, they are held in county jails, but to get to an immigration judge, they would likely go to one of the ICE Louisiana facilities, Byrd said.

If you commit a crime as an undocumented immigrant, the process becomes much more complicated. Byrd said outstanding criminal charges, whether federal, state or local, will also change how the process works for those detained. Peterson, who represents Vargas, says her client had not heard from her father by press time.

Trump and DACA

Before November when the U.S. elected Donald Trump as president of the U.S., immigration officials had a sort of preference system in place when it came to deporting undocumented immigrants. The Obama administration prioritized those who had committed crimes, were caught near the border and those arriving after 2014, an August 2016 NPR report says.

Deportations spiked at more than 400,000 by 2012, but then those numbers dropped in the last several years.

With Donald Trump's election and Jan. 25 executive order, the pendulum is set to swing in the opposite direction. The new president's order goes beyond the much-debated wall he plans to build.

"The Secretary shall immediately take all appropriate actions to ensure the detention of aliens apprehended for violations of immigration law pending the outcome of their removal proceedings or their removal from the country to the extent permitted by law," Trump's order reads.

This means the end of "catch and release" policies for undocumented immigrants and the possibility of the federal government and taxpayers paying for additional detention facilities to house undocumented immigrants. Trump's order cites drug and human-trafficking concerns as reasons to secure the border, but he fails to prioritize undocumented immigrants or mention DACA, putting a group of undocumented immigrants potentially in jeopardy.

"We don't know what's going to happen with DACA, one of the concerns is that because of the change in priorities, it seems as though you would be eliminating any type of preference system," Peterson told the Jackson Free Press.

DACA recipients are mainly millennials working or going to school in the country. To be eligible, recipients had to be under age 31 in 2012 and to have come to the U.S. before they turned 16 years old. Legislation pending in the U.S. Senate could protect DACA recipients and prevent them from deportation at least through the expiration date of their status.

Vargas is one of many DACA recipients in Mississippi in limbo currently, and not all of them will have access to legal representation. Peterson says Vargas' plans will depend a lot on what happens to her brother and father, but that she deserves to stay in America.

"She pays her taxes ... and is working a full-time job and went to school," Peterson told the Jackson Free Press.

UPDATE: On March 1, ICE arrested Daniela Vargas after she spoke out at an immigration rally in Jackson, Miss.

Last names of the family have been omitted for privacy and security reasons. Read more about immigration raids, facts and reality at jfp.ms/immigration.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus