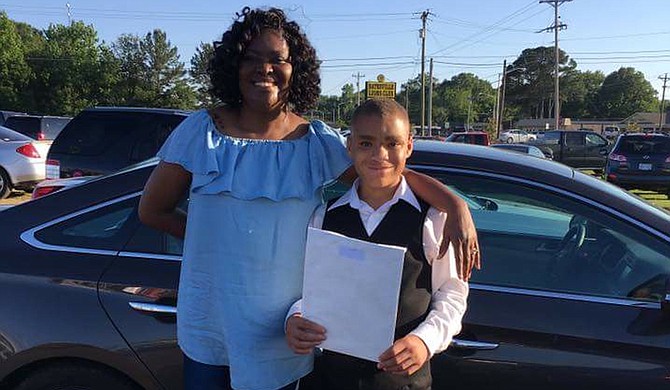

Along with her husband and daughters, Shavonne Thigpen (left) experienced wraparound services for almost a year to help the family support one another and her son, Terry (right), who suffers from autism and sensory and mental-health disorders. Photo courtesy Shavonne Thigpen

JACKSON — Terry Thigpen had been to four residential acute-treatment facilities before he was 10 years old, until his mother, Shavonne, discovered the Wraparound Initiative. It was an alternative to sending Terry away for treatment for his autism as well as sensory motor and mental-health disorders.

Instead, a team of facilitators could come to the Thigpen home and establish boundaries, help work on tensions and work to get Terry the community-based support he needs. Shavonne said the Wraparound program did not feel right at first, with lots of paperwork and professionals, from mental health-care practitioners to facilitators in the home. But it paid off after a few months, she said.

"(Once) everybody in the support system was following the objectives—because everyone was on the same page, we saw progress," Shavonne told the Jackson Free Press.

Shavonne and her husband have two daughters, both older than Terry, with one still living at home. She said the Wraparound facilitators helped her realize that her daughter felt forced to take on parenting roles when helping around the house with Terry.

"We didn't know she felt that way," Shavonne said.

The Thigpens live in Batesville, Miss., but to access additional services such as therapy for Terry, Shavonne drove him the 45 minutes north to Southaven every week. With the support at home and the encouragement to stay involved in the community, especially with other activities like sports teams for Terry, things at home got better.

Shavonne said the family used wraparound services for almost 11 months, and the family had no critical events with Terry over the following year.

Families at the Table

The School of Social Work at the University of Southern Mississippi runs what is now called the Wraparound Institute in coordination with the Department of Mental Health and Medicaid, which provide funds to offer the services to the state's most vulnerable young people.

Minors who are Medicaid-eligible and involved in other systems like the juvenile-justice system, Child Protection Services or about to be sent away for in-patient psychiatric care are eligible to participate in the Wraparound program, Tamara Hurst, an assistant professor at the School of Social Work, said. The program is unique because it gives the families a voice and a choice about what they want to do for their child's health and care.

"If the family is not engaged in the process, they are much less likely to follow through," Hurst said. "They are at the table; any decisions that are made, they are making those decisions."

Wraparound facilitators and therapists walk families through what their options are to get their child support—a different approach than a doctor telling the families what to do for their children. Canopy Children's Solutions, Youth Villages, Pine Belt Mental Healthcare Resources and other community mental health centers around the state are serving families around the state with the program. USM's role is mainly training facilitators in how to negotiate and facilitate family discussions and meetings.

The Wraparound program is also critical for moving the state away from institutional care for kids, focusing on kids receiving services that are community-based.

"For a long time, the go-to method or treatment was just put them in a hospital, let's put them in a hospital to stabilize them," Hurst said.

That's not the case anymore. Wraparound teams are available from the state's many mental-health providers, and the program is growing.

"We're hoping that families realize that this is available for them," Elizabeth McDowell, a coordinator at the Wraparound Institute, said. "Families don't know where to turn. ... [T]here shouldn't be anywhere in the state where they can't access wraparound, so we go everywhere in the state."

Still Struggling for Access

Wraparound services worked so well for Shavonne that she left her higher-paying job to work with other families. She is now a family -support specialist for Youth Villages in Hernando. She works with parents who opt-in to wraparound services. As a mother who has gone through the process, she can help other parents work through the sometimes-difficult process.

One family Shavonne helped has transitioned so well that the son went from stealing cars and using alcohol to graduating with his GED and working a part-time job, she said. Shavonne said her experience made her re-evaluate how she looked at her role as a parent, and she realized that she had to think about her son's future.

"I had to say it's not about me—I wanted it to be about me or my other kid, but it wasn't about me, it was about him and whatever it took for him," she said. "If I could say one thing (to other families), I would say, your reality is not going to change by ignoring the obvious. Seek the resources to help that child."

Wraparound is not a one-time fix, and mental-health and behavioral disorders do not go away overnight. Terry had to return to acute care when he entered his turbulent teenage years. Shavonne says she regretted not having a therapist in place for him at that time so he would have stable supports despite the changes he was going through physically and emotionally.

The Wraparound Initiative started even before advocacy organizations filed a 2010 lawsuit against the State of Mississippi for its over-reliance on institutionalization for its system of mental-health care for children. Mississippi received federal grant dollars to start the program, called MYPAC (short for Mississippi Youth Programs Around the Clock), and by 2011, Wraparound trainers from the University of Maryland came down to work with Mississippians at USM.

To date, the Wraparound program has helped thousands of vulnerable kids in the state. Data from the USM School of Social Work shows that almost 3,000 kids received Wraparound services in fiscal-year 2016, with 2,335 of those children diverted from out-of-home placements in institutions.

Funding for the Wraparound Institute does not appear to be a part of the large budget cut the Department of Mental Health will face starting this July.

The Legislature directed DMH to prioritize funding for community-based services, after the federal government sued the department for its adult system of mental-health care, in the appropriation bill for the agency.

The 2010 lawsuit filed initially to support more community-based services for kids in the state, like Terry, is now a lawsuit on behalf of one Mississippi child.

Now Terry is 14 and about to enter high school. Currently, Shavonne still drives him the 45 minutes to Southaven for therapy once a week and group therapy twice a month. She said Wraparound services made both Terry and her as his mother accept him for who he is.

"He is going to be who he is going to be, often times ... (and) the services offered through Wrap(around) help him to accept him better for who he is and allowed me to get services he needs," Thigpen said.

Email state reporter Arielle Dreher at [email protected].