OXFORD—I'll never forget Danny Glover as the drifter Moze in the 1984 film "Places in the Heart." It was a Depression-era story of a widowed mother in the South trying to keep her children and save her farm with the help of Moze and a blind war veteran.

I loved that story because it reminded me of my grandmother, Minnie "Mama" Atkins, herself a rural southern widow during the Great Depression who had to fend off local authorities who wanted her to give up her four small children.

Later I saw Glover as Joshua Deets in the 1989 television series "Lonesome Dove." He was one of my favorites among the large cast in that 19th-century cattle-drive tale that my family watched religiously, episode after episode.

I never imagined I would eventually get to meet Glover, not so much as an actor but as a champion of working folks and their rights to organize and have some control over their lives at the workplace.

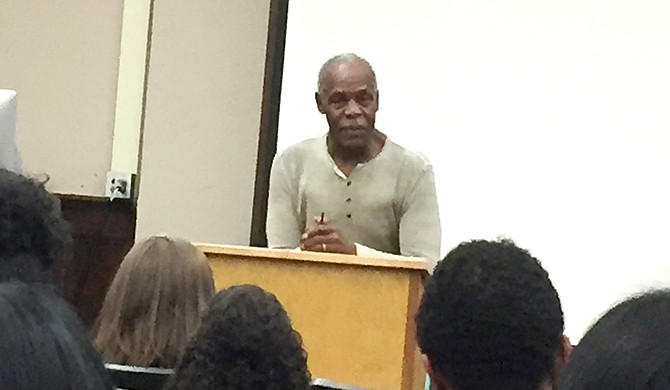

Glover was here in Oxford recently to rally students and citizens to come to Canton on March 4 and join U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders in the "March on Mississippi" against voter suppression and for workers' rights, particularly in the ongoing union-organizing effort at the giant Nissan plant in Canton.

He told the crowd of more than 100 a story about legendary actor, singer and human rights activist Paul Robeson, who suffered the blacklist and widespread scorn because of his political advocacy. Asked if he regretted anything in his life, Robeson said, "There's not one thing I'd change in my life. It's about the journey."

Young people today would do well to think about their own journey in life, said Glover, 70, whose labor advocacy and human-rights efforts have earned him an international reputation. They need to listen to the stories of those around them, particularly the shared humanity of those who work hard and play by the rules yet whose rights as humans are constricted by the powerful.

"I think about the journey. Over 50 years ago as a student, I didn't know where that journey was going to take me. ... You have an opportunity to look at the stories and make them part of (yours)," he said.

In Canton, thousands of men and women work at an automobile plant that was built with the help of $1.4 billion in tax breaks and other incentives that Mississippi, the poorest state in America, provided. While they earn good wages in comparison to other Mississippians, they live in fear that they'll lose their jobs due to injuries in a workplace that the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration recently fined $20,000 for poor safety conditions.

They see their jobs increasingly threatened by management's hiring of temporary workers who receive fewer benefits and lower wages. They worry that their management will find reasons to get rid of them if they show support for joining a union despite federal laws that prohibit such intimidation. For more than a decade, a community-wide effort has been underway to get Nissan to desist in the kind of voter suppression that makes a free union election impossible.

Glover said even though the South has changed, the fight for workers' rights continues. "The rights of workers have been curtailed, stepped upon," he said, adding that those rights will continue to be curtailed "without a union, a place where workers can go to collectively bargain, to have a conversation."

Glover said it was his first trip to Oxford, but he has come to Mississippi several times to bring attention to the cause of the Nissan workers in Canton, 80 percent of whom are African American.

"When I see people win, they stand a little taller," he told Nissan workers during a visit in 2012. "I want people to win, people lifting themselves up."

Glover told them that he came from a union family. His parents were postal workers who were also active in the Civil Rights Movement. "I had health care all my life because the union created the situation where I could have health care."

He also told the workers something that was echoed during his recent Oxford visit: "You are all part of a much larger legacy. Your story is going to resonate."

Joe Atkins is a veteran journalist, columnist and professor of journalism at the University of Mississippi. Email him at [email protected].

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus