There may not have been any NFL game in the 1980s more important than the 1982 NFC Championship Game. The game was a turning point in the fortunes of both the Dallas Cowboys and the San Francisco 49ers.

Dallas built a dynasty in the 1970s that continued into the early 1980s with numerous future-Hall of Fame players on its roster. San Francisco spent much of the 1970s as a losing franchise, but the arrival of Head Coach Bill Walsh and quarterback Joe Montana turned the franchise around.

The changing of the guard happened on Jan. 10, 1982, when both teams battled for the right to reach Super Bowl XVI. Dallas wasn't about to give up its stranglehold of the NFC easily, as the team clung to a 27-21 lead in the fourth quarter.

Montana drove San Francisco to the Cowboy's six-yard line and took a second timeout with 58 seconds left. Facing third down and three yards, and needing a touchdown, Montana took the snap.

Dallas' defensive line wasted no time breaking through the 49ers' offensive line and chasing Montana as he rolled right. As the Cowboys defense closed in, Montana pump-faked (acted like he was going to throw the ball) once and then twice as he neared the sideline.

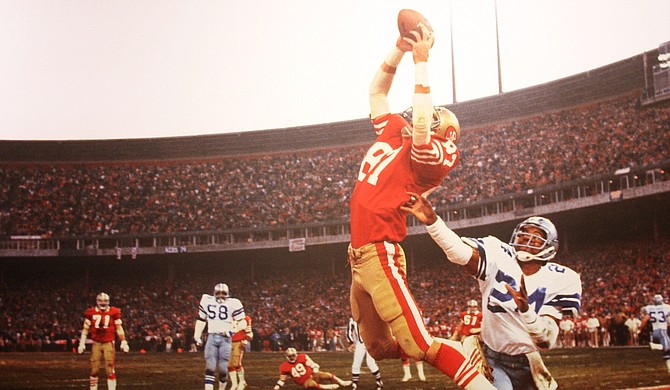

Montana lobbed the ball just over a sea of Cowboy defenders' hands, and wide receiver Dwight Clark, who was drafted in the 10th round out of Clemson University, made one of the greatest leaps in NFL history.

Before making the catch, Clark lined up on the right side of the play and was double-covered in the end zone as he cut toward the middle of the field. He turned on a dime and broke toward the right sideline, the same direction that Montana had been rolling. Leaving both defenders behind, the 6-foot, 4-inch receiver jumped as high as he could and hauled in the pass in the back of the end zone, tying the game at 27-27 with 51 seconds left to play.

San Francisco kicked the extra point and took a 28-27 lead, and the 49ers' defense closed out the game with a sack fumble of Cowboys quarterback Danny White, which sealed the win.

Dallas slowly saw its dynasty come to an end over the early 1980s. San Francisco went on to defeat the Cincinnati Bengals, winning the Super Bowl at the start of its dynasty.

The play to win the NFC Championship Game became known as "The Catch" and became one of the most iconic grabs in NFL history. Clark's reception also helped establish Montana's cool-under-pressure reputation.

Clark made eight catches for 120 yards and two touchdowns in the 49ers' win. The game-winning score happened because he and Montana had practiced high heaves into the end zone ever since they entered in the league together in the 1979 NFL Draft.

Playing for San Francisco from 1979 to 1987, Clark won two Super Bowls, made 506 receptions for 6,750 yards, caught 48 touchdowns and ran for 50 yards. He led the league in catches during the strike-shortened season of 1982 with 60 grabs, and was in the 1981 and 1982 Pro Bowls.

After Clark ended his career, the 49ers retired the former star receiver's jersey number, 87, and Clemson University inducted him into the school's Hall of Fame. He also spent time as general manager for both San Francisco and the Cleveland Browns.

Mostly, Clark has spent his post-football career out of the spotlight. That changed on Sunday, March 19, when he revealed that doctors diagnosed him with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as ALS or Lou Gehrig's disease, which is a degenerative disease that affects the nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord.

In a statement released on former 49ers owner Eddie DeBartolo Jr.'s website, Clark wrote that he believes playing football played a part in the disease's onset. He encouraged the NFL and NFL Players Association to keep working together to keep head trauma out of the game.

Scientists still debate the link between ALS and playing football. A 2012 article in the medical journal Neurology reported that professional football players wer four times more likely to die of ALS than the general population. More recently, a piece in The Atlantic in June 2016, which also references the Neurology article, pointed out that several former NFL players have been younger than the normal age for an ALS diagnosis, but the connection needs further study.

In a story from the San Francisco Gate Chronicle, doctors such as Dr. Sam Gandy, the director of the Center for Cognitive Health and the NFL Neurological Care Program at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, acknowledged the potential link between football and ALS, and said that the link is controversial, partially because it went undetected for a long time.

Clark and former New Orleans Saints safety Steve Gleason are just two of the numerous players to be diagnosed with ALS. The Chronicle story noted that three players from the 1960s, Bob Waters, Gary Lewis and Matt Hazeltine, died of ALS.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus