As an introverted audiophile, Seth is happy to spend his days walking around New York City, recording the sounds that he hears before heading back to the studio he shares with his wealthy college friend, Carter.

During one walk, Seth unknowingly captures a man singing the blues while playing chess in the park, and soon sets him and Carter on a path that leads through darker parts of America's music industry.

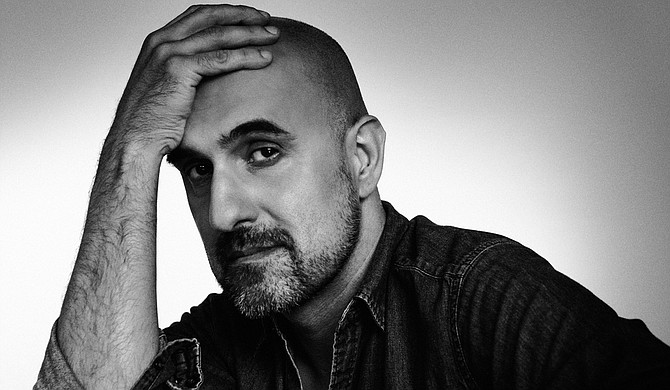

Of course, that's only a sliver of what's at play in British-born author Hari Kunzru's fifth novel, "White Tears" (Knopf, $26.95, 2017), which hit shelves on March 14. Through its narrative, the book also delves into the history of blues music and the cultural appropriation that haunts the genre today. Oh, and it's a ghost story.

To those who aren't familiar with his critically acclaimed past works, such as 2011's "Gods Without Men," Kunzru is known for his lively writing style and his ability to bring seemingly disjointed elements together to poignant ends. In the case of "White Tears," the story began with his love of blues music and a fascination with its history.

"I think I've taken a journey that a lot of people take," he says. "The way that I kind of use in the novel is that I started off as a young guy listening to blues rock and all those '60s British bands—Led Zeppelin, the Stones and so on—and then gradually realizing that they came out of something older. So you go back into Chicago, and the blues and R&B, post-war stuff."

The second half of the book's origin is a darker story, Kunzru says. He moved to the U.S. in 2008 for a fellowship at the New York Public Library and was around for the election of former President Barack Obama. During that time, he says, news commentators were eager to suggest that we had arrived at a post-racial America, which, of course, the past several years of racial issues have disproved.

"I wanted to write a kind of uncanny book because I think so much of this racial tension in the U.S. is to do with people not acknowledging the past," he says. "You know, feel guilty or don't feel guilty. I think all of that is kind of irrelevant, in a way. People get very uptight about how they feel that they're expected to react, but actually, people don't know a lot of their history. But it's still there. All the results of it are still around."

Given the book's focus on American music and American race relations, Kunzru says he understands that some readers may have a negative reaction to him wading into those waters.

"It's an odd position to be in—I can fully accept that," he says. "You know, I've come in from the outside, and in a particular sense, I have no damn business getting mixed up in this at all. But I think it also kind of gives me an advantage in a very particular way."

Kunzru grew up in Essex as the child of an Indian father and a white English mother in a majority white suburb, and questions of race became part of his daily life from a young age. While he says that his background means that he's implicated in all sorts of other ways, it does make him something of an outsider to the American racial climate and allows him to tell the kind of complex, gray-area story that he wanted.

"I think it's very hard for black Americans and white Americans to talk to each other about this, and it's very hard for anybody to write anything that's as ambiguous as this novel I've written," he says. "... It's a book that has this kind of element of revenge that I think, maybe if a black American writer wrote it, they would get a lot of heat that I wouldn't get, and maybe a white American writer would feel uncomfortable writing these white characters saying these kinds of casual, low-level racist things.

"And I mean, fools rush in where angels fear to tread, so maybe that's the story of this book," he adds with a laugh.

Hari Kunzru signs copies of "White Tears" at 5 p.m., Wednesday, March 29, at Lemuria Books (Banner Hall, 4465 Interstate 55 N., Suite 202). For more information, visit harikunzru.com.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus