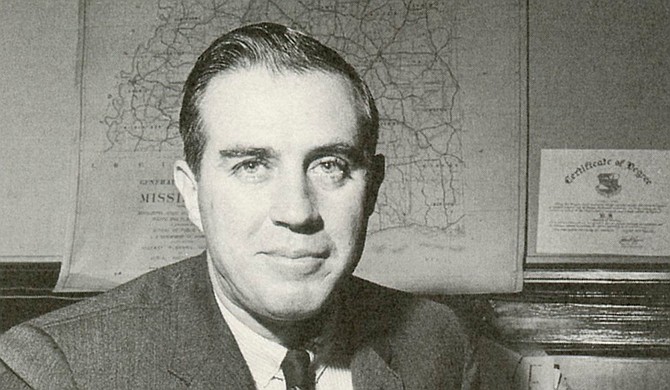

“To be a journalist is to be prepared to take a risk,” he said. “Newspapers are closest to my heart. I see us engaged in an endless war. This is not just a cozy political sideshow.” —Bill Minor Photo courtesy Flickr/Ellen Ann Fentress

In 2004, the now-deceased Mississippi journalist Bill Minor gave an assessment of his profession. Among its problems, he said, was that too many of his colleagues would rather play "go along, get along" than risk the consequences of the truth. "To be a journalist is to be prepared to take a risk," he said. "Newspapers are closest to my heart. I see us engaged in an endless war. This is not just a cozy political sideshow."

This anecdote from an April 2017 Jackson Free Press story reminds me of what journalism professor Michael Schudson calls the "peculiar standard" of news objectivity. That standard dictates that journalists present "both sides of the story"—a form of "go along, get along" journalism that has provided the industry, or the public, few benefits.

In "Discovering the News: A Social History of American Newspapers," Schudson defines objectivity as "a faith in 'facts,' a distrust in 'values,' and a commitment to their segregation." He calls the concept "peculiar" for a couple of reasons: First, objectivity did not exist as the hallmark of American news reporting before the early- to mid-20th century, when the industry began recognizing it as a way to neutralize sensationalism and partisan journalism that defined news reporting. In 1919, Walter Lippmann called for journalists to adopt "the scientific spirit ... a common intellectual method and a common area of valid fact" in their journalism.

Schudson also defines objectivity as "peculiar" because we still trust it as a reliable means of validating facts—in much the same we trust medical examinations—even though the belief in objectivity is, Schudson notes, more of "a moral philosophy, a declaration of what kind of thinking one should engage in ..." than the scientific accreditation of information that journalists insist it is.

By the mid-20th century, the industry concluded that objectivity, while impossible to achieve, was worth chasing nonetheless. In more modern times, that pursuit created a climate in which many journalists no longer trust their professional instincts, or if they do, they fail to act upon them. The consequences of its faith in objectivity has made the fourth estate—a label describing the newspaper's part in monitoring the political process—play the role of inconsequential observer to some of the most important, and reckless, political events in recent memory.

The industry's allegiance to objectivity means, in recent years, "playing it safe" in times of political urgency—giving credibility to news that is not subjected to strict and dogged evaluation, giving otherwise suspect sources (or political candidates) the benefit of the doubt against one's better judgement, or giving unreasonable, even unhinged, "surrogates" the airtime or space to print. It is enough for most reasonable people to ask: Since objectivity is impossible, should journalists continue to chase that particular unicorn? If not, what's the alternative?

Here's one suggestion: Perhaps journalists should no longer try to separate facts from values. After all, aren't value judgments needed when assessing the truthfulness of facts? Perhaps it's time, then, to say that Lippmann was full of it for suggesting we apply the "scientific spirit" to journalism. Instead, journalists should put value judgment back into their craft; let's start with honesty, courage and integrity, and work from there. The absence of, or lip service to, any of the above explains in part why we ended up as spectators to the 2016 political circus, and why the "cozy political sideshow" that Minor spoke of is now a packed house.

Pete Smith is an associate professor in the Department of Communication at Mississippi State University and the JFP's new media columnist. This column does not necessarily reflect the views of the Jackson Free Press.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.