The Mississippi Legislature paid half a million dollars for a detailed BOTEC study of Jackson crime that specifically warns that a child put into police cars and behind bars—with the inevitable mugshots bandied about—is more likely to commit worse crime as an adult. Photo courtesy Flickr/Tex Texin

The 13-year-old was wearing a brown T-shirt with Michael Jackson stretching his arms high into the air, his signature white fedora pulled low over his eyes. Above the white image of the King of Pop, the boy wasn't smiling and looked blankly at the camera, his shoulders slumped downward. His dark skin was smooth and young.

This adolescent's mugshot flew out on the Jackson Police Department's Twitter feed on Aug. 30, 2017, because he had been arrested for a heinous crime—armed robbery and carjacking of a 61-year-old. The Clarion-Ledger then ran it large on the front page of its website. If the boy did it—and he's still innocent until it's proved in court—his life may be over. He presumably will be tried as an adult even though a 13-year-old is still more than five years away from the mental capacity of an adult.

When I complained about the mugshot, I got the usual responses from the tough-on-child-crime gallery—if he didn't want to be treated as an adult, he shouldn't have done an adult crime, blah blah. We heard the same thing about 12-year-old Tamir Rice in Cleveland, Ohio, when a cop killed him for pointing a toy gun their way.

In fact, there are rare instances when police or media should publish photos or even names of juveniles. And the most unconscionable time to do it is after a young suspect is in custody. You got your boy, cops. At that point, it's just bragging.

But why not publish the pictures? Glad you asked. Because (a) the kid isn't convicted, yet, (b) the kid may still be innocent and, if so, (c) the experience could actually turn a child toward a life of crime and (d) result in more victims.

Take the infamous case of the rape and murder of 11-year-old Ryan Harris in Chicago in 1998. My Columbia j-school mentor LynNell Hancock, who specializes in reporting on children, uses this murder as a case study in responsible journalism about children. Two little boys, 7 and 8, were arrested for the murder. The media ran their perp pictures in handcuffs widely.

Rush to Judgement: Trying Kids As Adults

A long-form look at the problems of trying kids as adults—and coercing their confessions.

As often happens with not-fully-developed young minds, the children gave false confessions. DNA later proved an adult did it. But they were considered killers for a month when everyone believed they did it. The damage was arguably done. One of them was later arrested at age 15 for a gas-station shooting. Maybe he would have been there anyway, but maybe not.

It's hard to get media in our state to notice (ahem, Clarion-Ledger and every dang news station), but the Mississippi Legislature paid half a million dollars for a detailed BOTEC study of Jackson crime that specifically warns that a child put into police cars and behind bars—with the inevitable mugshots bandied about—is more likely to commit worse crime as an adult.

Now imagine if that kid is actually falsely accused. The damage to him and the community may already be done.

But those Chicago kids were younger than 13, you might respond. Well, the Central Park 5 were older.

I was in New York City when the (racist) phrase "wilding" came about in response to the attack and rape of the woman known then as the "Central Park jogger." The NYPD caught the young crew of four black and one Hispanic teenagers (all were 15 and 16 and from Harlem) supposedly out looking for a woman to "wild."

Cops then coerced false confessions including ratting out each other.

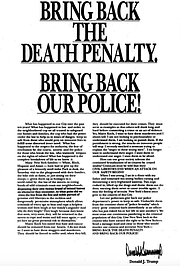

Meantime, business tycoon Donald Trump took out full-page ads calling for their execution in 1989, saying among other things: "How can our great society tolerate the continued brutalization of its citizens by crazed misfits?" The five teenagers were convicted of charges including assault, robbery, riot, rape, sexual abuse and attempted murder.

It's good that folks didn't listen to Trump because it turns out that they were innocent, even though all of them served from seven to 13 years in prison. But they were demonized and treated as if they were guilty before they were tried; I remember it well. I'm embarrassed to say that it never crossed my mind that they were innocent. This was the famed NYPD, after all. They knew what they were doing, right?

The point is that disseminating mugshots of minors should be rare due to the harm that it can cause to that kid and society to treat children as adult criminals, especially before they even get a trial. I remember a time when most media would actually question using mugshots of minors and know that it's not ethical unless needed, say, to catch a suspected killer on the loose.

But, sadly, the age of "superpredator" mythology took hold in the 1980s for young people of color and hasn't let up even as it's been proved false (and even as juveniles of color are more likely to be victims of violence than perpetuate it). The American Psychological Association released a study earlier this year showing that people believe that men of color are more threatening and larger than white counterparts even when they aren't. And a 2014 APA study showed that black boys as young as 10 are "more likely to be mistaken as older, be perceived as guilty and face police violence if accused of a crime," which explains people blaming young Rice, 12, for his own death.

Note that these aren't just white people viewing males of color this way. Likewise, it's not just white officials deciding to send out mugshots of 13-year-olds already in custody in Jackson. That kid is now already scarred and branded as a hardened criminal, no matter guilt or innocence.

This is particularly ironic in a city where many support a district attorney who declines to push prosecution of grown men for crimes including beating and dangling a woman off a bridge—and where officials also fire out mugshots of children. This cognitive dissonance is in no way making our city safer. And the trauma that can result from unneeded exposure of children to criminal-justice horrors is exactly what experts warn can turn into lifetimes of crime. Kids just aren't scared straight; it often has the opposite effect, in fact.

If he committed this crime, the 13-year-old needs help and the kinds of intervention that can both rehabilitate him and prevent future crime. As the mayor likes to say, the police cannot really prevent violence. But with due respect, his police department can make violence more likely if they don't adopt evidence-based practices for dealing with child suspects.

Read more about smart youth-crime prevention at jfp.ms/preventingviolence.

More like this story

More stories by this author

- EDITOR'S NOTE: 19 Years of Love, Hope, Miss S, Dr. S and Never, Ever Giving Up

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Systemic Racism Created Jackson’s Violence; More Policing Cannot Stop It

- Rest in Peace, Ronni Mott: Your Journalism Saved Lives. This I Know.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Rest Well, Gov. Winter. We Will Keep Your Fire Burning.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Truth and Journalism on the Front Lines of COVID-19

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.