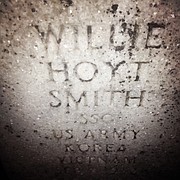

Donna Ladd's stepfather Willie Hoyt Smith (pictured front row, talking to commander) fought in the Korean War and later went to Vietnam twice during a 20-year military career. Like many southerners, the 1951 graduate of Dixon High School in Neshoba County lived and worked alongside racially diverse peers for the first time in the military. The location of this photo is unknown. Photo by Photo from Donna Ladd's Collection

JACKSON, Miss. — When I woke up to NFL players, coaches and owners kneeling and linking arms defiantly against Donald Trump’s attack on American freedom this morning, I thought of my stepdad, Hoyt Smith. I had started calling him Daddy in the fourth grade when my mother married him after his first tour in Vietnam, and we moved to Fort Benning, Ga., with him.

In our little Georgia apartment, I first heard him yell in the middle of the night. Running into the bedroom, I saw him behind the bed shouting for his fellow soldiers to “Take cover now!” as my mother tried to get to him to help.

I remember Daddy, who served the country for two decades, crying one time when he’d had too much bourbon again and telling me about his best buddy in the fields of Korea being blown to bits right next to him and how he had to kill, too, to make it out. I remembered him talking about that time he attacked his sergeant because he woke him up in the middle of the night, and my dad thought he was under attack. He punched the sergeant before he realized who it was, later costing him a promotion and more money.

I remember him being sent back to Vietnam from Benning because he hadn’t quite served his whole 20 years yet, leaving my mother and me in our trailer back home in Philadelphia, Miss., for over a year, missing and worrying about him as he sent home letters showing his despair.

I remember him coming back from Nam even more alcoholic than when he left; we could tell if he’d had one sip of bourbon from the look on his face. That was when his anger and desperation came out. When I was a little older, he told me how his commanding officers when he was a young soldier in Korea had practically poured liquor down their throats in the makeshift canteens to help them not think about their daily lives: the severed limbs, the bloody bodies, the stench of war.

I remember my happy-and-tortured teenage years when Daddy taught me—his only child—to love football and basketball and know as much as the guys in homeroom at Neshoba Central. The sports talk was our main connection when he wasn’t drinking, and raging, and destroying the little we owned.

I remember Daddy, whom I loved with every ounce of my being, getting drunk and being mean to my mama, who loved him with every ounce of her being until the day she died, just as he loved us in whatever ways he could muster. I recall him disappearing, getting in fights, driving drunk, even accidentally firing a gun through the front door. He then would sober up and go buy us piles of decadent cakes and pies (although he was diabetic), or take me shopping for piles of school clothes, or show up with a new car he’d traded for that we couldn’t afford—to my mother’s chagrin.

I remember him and me playing hide-and-seek with the cats, or opening the Christmas presents and rewrapping them again before mama knew, or him doing crazy voices and creating ongoing monologues from every billboard we’d pass on the road with a country-music soundtrack from our 8-track tapes. I smile now thinking of the road trips with our Siamese cat Tom T (he named him) riding next to his headrest, and him slamming the brakes to throw the regal cat off—and us all dying laughing. I also remember when Tom T dug his claws in and hung on, yowling loudly back at my dad.

I remember when the horrors of war flooded back in, and him drowning them or barking again at his fellow troops from behind a door. I remember him showing up at my mother’s funeral from Florida, several years after she finally chose her sanity over her broken heart and kicked him out. Sober in those days, he stood at McClain-Hays and cried like a baby, telling me how sorry he was for all the pain he caused us and how much he loved us both, which I already knew. He soon moved back to our hometown, rented a trailer and got a cat so I would have a place there still and keep coming home to see him. The next year, he and his feline "rascal" nursed me through a bad kidney infection in that little mobile home, my last quality time with him. We watched sports and talked football when I wasn't sleeping.

When he was dying from lung cancer in the VA hospital in Jackson a couple years later, we watched them-damn-Saints (as he always called them) play the Giants as he searched for every breath.

A few days later, I stood in the Morrow Cemetery near Dixon in Neshoba County and listened to the military trumpeter I had insisted be there to play “Taps" so I could bury him next to his mother with the dignity a soldier deserves. I accepted the folded American flag from a gloved Guardsman and hugged it after watching my last parent go into the ground. I asked for a military tombstone to honor his sacrifice, and I still have his medals for bravery and service that he earned for mortgaging his future to fight for this country’s ideals of freedom of choice, belief and expression.

I didn’t know it that day in Daddy’s cemetery, but I was burying him just rows away from ancestors that he and I shared. I didn’t know then that my stepfather and I came from the same Watkins family who helped build that part of Neshoba and neighboring Leake County. I wouldn’t have imagined then that I, and he, descended from farmers and businessmen who actually owned land, and people. I didn’t yet know how many Confederate soldiers were in our family line and how Daddy and I both came directly from a heritage of white supremacy where black people were inferior and punished by law enforcement and lynch mobs if they dared demand anything approaching the same rights as white Americans. Like most white Mississippians, I'd naively assumed that my people were too poor to buy slaves.

I think of the only father I really got to know well, warts and all, and how he went as a young man to a foreign land to join a diverse force fighting for the American ideals of democracy and freedom, including free expression, press freedoms I enjoy now and the right to protest. That freedom extends to white supremacists marching in Charlottesville, anti-war protesters burning a U.S. flag, neo-Confederates marching to support the rebel flag and, yes, to NFL players taking a knee during the national anthem to demand the end of police brutality and profiling.

I believe that today my beloved veteran of foreign wars would stand, or kneel in spirit, with the NFL players who are pushing back on Trump’s treatment of them as chattel entertainment, calling for them to be kicked out to pasture if they dare exercise their rights to question and challenge that Willie Hoyt Smith left so much behind in Korea to maintain.

Daddy loved football, and he loved the players, and I never heard him refer to people in racist ways, probably because he shared foxholes with men of all races. His love of the game, and his encouragement of me to go ahead on and stand up for people, helped me become a lifetime football fan, and understand the price many soldiers, including athletes, paid to help cement and grow American freedoms.

Black players, including Colin Kaepernick, do not deserve degradation and threats because they stand up for people of color who still do not enjoy the same privileges, rights and protections as white citizens. There is nothing more American than these players demanding equal protection from cops, politicians and juries for themselves and all citizens. We must honor these players’ courage and that of soldiers like my daddy fighting to keep pathways to freedom open for every single person. No matter how imperfect the nation back home was at the time, U.S. soldiers as a collective have long put themselves on the front line to uphold our ideals of freedom.

So are these players. They deserve our respect and our support.

Donna Ladd is a long-suffering New Orleans Saints fan and hater of the Dallas Cowboys, until Dak, that is (but is still not a fan of Jerry Jones). And, yes, she still has cats. Her oldest is named Willie Hoyt. Follow her on Twitter at @donnerkay.

More like this story

More stories by this author

- EDITOR'S NOTE: 19 Years of Love, Hope, Miss S, Dr. S and Never, Ever Giving Up

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Systemic Racism Created Jackson’s Violence; More Policing Cannot Stop It

- Rest in Peace, Ronni Mott: Your Journalism Saved Lives. This I Know.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Rest Well, Gov. Winter. We Will Keep Your Fire Burning.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Truth and Journalism on the Front Lines of COVID-19

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus