“Orange Is the New Black” author Piper Kerman’s experiences in a women’s prison have been a catalyst for her work in criminal-justice reform. Photo by Michael Oppenheim/Lyceum Agency

For five years, audiences across the world have tuned in to watch Netflix's hit show "Orange Is the New Black." The comedy-drama became a cultural phenomenon early on, earning a dozen Emmy Award nominations in its first season and picking up a GLAAD Media Award, a Peabody Award and many other acknowledgements along the way.

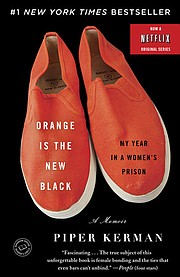

Despite the show's popularity, some viewers may not realize the story of lead character Piper Chapman is loosely based on the true story of author Piper Kerman, laid out in her memoir, "Orange Is the New Black: My Year in a Women's Prison" (Spiegel & Grau, 2011, $16).

Like her TV counterpart, a romantic partner introduced Kerman into a heroin-smuggling ring, and although she left that life after a short time, her decisions led to an indictment for drug smuggling and money laundering nearly a decade later.

After getting out of prison in 2005, Kerman faced a decision: put the experience behind her or use it to effect change. She began advocating for criminal-justice reform, most recently through her work with organizations such as the Women's Prison Association and as a creative writing educator in Ohio state prisons.

The Jackson Free Press recently got on the phone with Kerman, who will be the guest speaker for the Greater Jackson Arts Council's 2018 Creative Impact Luncheon on Aug. 23, to talk about the reality in "Orange Is the New Black" and the role of the arts in prison reform.

Many people know "Orange Is the New Black" but are maybe more familiar with the show. It's one thing to tell your own story in the book, but what was it like to trust someone to adapt it?

The adaptation obviously is not a biopic. [Laughs] Even in the very first season, there are these big deviations from the true stories that are told in the book. But I think the thing that's most important about the adaptation is not anything related to my own personal stories, but the inherent truth of all the stories and all the protagonists it represents.

So some of the characters are familiar adaptations of people who appear in the book. So there's a "Pennsatucky" in the book, and there's a "Crazy Eyes" in the book, though both of those real people are very, very different from those characters. There are some of the characters in the show who are not adapted from the book, like Gloria, but have these incredibly truthful, real stories. And that's the thing that makes me really happy about that adaptation.

You know, I think, stepping back, it's hard to do an adaptation from the page, from a book, whether it's fiction or non-fiction (brought) to the screen. The screen, television or film, is just a very different medium. It's much more reliant on external conflict, right? Person-to-person conflict.

It's a much harder medium in which to illuminate internal conflict, introspection. You often have to turn to a book for that. So the two are different in many, many ways, but I couldn't be more grateful and happy that someone has created this.

(Show creator) Jenji Kohan wanted to adapt the book, and of course, Jenji attracted so many incredibly talented people to work on it, and here we are already at work on the seventh season, so I'm thrilled. Among Jenji's previous work, I was most familiar with "Weeds," so I understood sort of the tone and approach of that show.

... It's not a surprise to me that she took that approach. It obviously does differ from the book. I think that I do have a sense of humor, but the book is not comic. The show is sometimes comic, but it's sometimes incredibly tragic, and that's an honest reflection of what it is like to survive behind the walls of a prison.

There are times when you're incarcerated where if you didn't laugh, you would cry, and it's important to include those moments, right? That's part of being human, and that's what I wanted to do with the book and hopefully what the show has done, is really establish these people as protagonists who happen to be prisoners.

I really hope that fans of the show extend their thinking about these characters they love so much to the real people who are right there in their community, in their states, who are part of the same (group) who have either done time in the past or are doing time now.

Even in the subtitle of your book, you don't shy away from the fact you spent a relatively short amount of time in prison. Why was that important to you?

I came home from prison in 2005, and you know, I was very lucky. I spent a short amount of time in prison. I served 13 months of a 15-month sentence. I was much, much more fortunate than many of the women I served time with. I had a safe place to live. I had a job. I had access to health care. I had many, many things. You know, I had a college education that no strip search could take away from me.

So I came home, and I was very conscious of the fact that all those privileges and benefits were going to help me come home successfully, with support and love from my family and friends. And I really want that for everybody.

But it was important that—you know, I had potentially more prospect at "putting this experience behind me," but I just couldn't really do that. I felt like I had seen and witnessed a lot of injustice in the criminal justice system, ironically, and that many people in this country have no idea what's happening.

More people ought to think about that and know about it if we're going to be the most incarcerated society in history, which is what we are. There is no society that has ever locked so many of its people up.

So I think people need to be much more aware of that reality and why that's true, how much race has to do with who is incarcerated and who goes into the criminal justice system—that's a huge determinant factor—and how much poverty determines who goes into the criminal justice system—that's a huge determinant factor.

Then, when people have been informed, they can (decide) whether they really think it's a good thing for us to be the most incarcerated society in human history. Everyone has to make up their own mind about that, but people should be well informed about who's really behind bars in this country and why that's so.

For a while now, you've been involved with advocacy for prison reform. How has that experience affected you?

I am an inherently glass-half-full person, which is a reflection again of having a fortunately safe childhood and an education—there's a reason I'm an optimist; I have reason to be optimistic. But I've been so encouraged.

I've been to 48 states in this country now, and I've met people all over the country, and people are very interested in talking and thinking more about these questions because, of course, everyone has some sort of (connection to them), even though not everyone's family has actually gone through the experience of incarceration.

But you know, these questions bedevil every single community, and they're very serious problems that confront us, in terms of substance-abuse disorder, in terms of violence between intimates—you know, almost all violence is between people who know each other—and in terms of mental illness. And the blunt truth is that prisons and jails are not good tools to fix those problems, and yet, that's exactly what we task them to do.

I think many people in this country, after 40 years of mass incarceration, are alert to the reality that what we're doing currently is not working. People are interested in dialog, in learning more and talking more, and there is an increasing interest in holding the people who operate the criminal justice system more accountable.

That's sort of the ironic truth, that police and prosecutors and judges and correctional workers are often not accountable for what happens under their watch. We see that with police violence, we see that with false convictions, and we see that with some of the abuse that happens within prison walls.

And I think there is an increasing call for people who we've endowed with a great amount of power over other people's lives to be more accountable and to make better choices themselves. ... That kind of conversation needs to happen at the local level, at the city level, at the county level. That's where the action is.

A lot of your advocacy work has revolved around things like creative-writing programs for inmates. Why do you feel the arts are important to combat these problems?

Well, there are several reasons. So yeah, I live in Ohio now, and I teach narrative nonfiction writing in two state prisons there: a men's medium-security facility and the primary women's prison in Ohio. And I do that because, first and foremost, I was so fortunate to be able to share my own story, and I think that we should have a lot more stories to really understand where we're at.

A single story could never explain something as complex as the American criminal justice system. But I think for that to happen, we really have to listen to the men, the women and the children—because we do lock up a lot of children in this country in the juvenile justice system. We really want to understand how are we at this point where we're at.

... These stories are fascinating and incredibly compelling, and some of them are funny, and some of them are, I can't even tell you how heartbreaking. But when they learn how to tell their story in a way that is more easily understood by a wider number of people, I think that's important for them, as well. I think my students start to recognize that their stories and their lives are important, and quite frankly, many of them, especially my female students, have been told their entire lives that their lives are not important.

We're talking about some of the most marginalized people in our communities, whether you're talking about people of color, whether you're talking about sex workers, whether you're talking about mentally ill people or people with substance-abuse disorder. These are people we push to the margins of society. We tell them directly or we tell them with our actions that they're not important.

When my students get to tell their own story on their terms, they start to recognize the importance of their lives, and that's a really important turning point for them to then have a greater sense of agency over their lives. I love this work. I've done it for almost four years now, and it's one of the most important things I've ever done.

The GJAC Creative Impact Luncheon is Thursday, Aug. 23, from noon to 1:30 p.m. at the Old Capitol Inn (226 N. State St.). Admission is $50 per person. Visit greaterjacksonartscouncil.com.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus