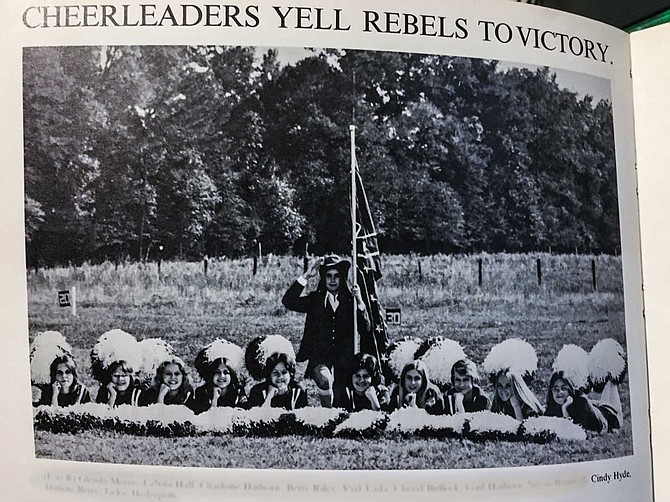

Young Cindy Hyde-Smith, third from right, attended a Confederacy-worshiping segregation academy opened in 1970 to counteract forced integration.

JACKSON — Pop diva Britney Spears once attended Parklane Academy in McComb—which even today prohibits pregnant students or students who were previously pregnant from attending or re-entering.

The handbook for Hillcrest Christian School in Jackson—where Gov. Phil Bryant graduated when it was called Council McCluer and distributed "scientific racist" literature to students—advises that girls there may be asked to take a pregnancy test.

Northpoint Christian School in Southaven specifically cites "homosexuality" as grounds for expulsion for any student "who promotes, engages sin, or identifies himself/herself with such activity through any action." Madison-Ridgeland Academy in Madison, meanwhile, bans students from hairstyles like "twists," "cornrows" and "dreadlocks."

The Jackson Free Press' Nov. 23 report that Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith attended one of Mississippi's first segregation academies, complete with Confederate flags and regalia, and later sent her daughter to one, has spurred a national conversation on schools set up to separate white kids from African Americans. At least six private Mississippi schools that started as segregation academies in the 1960s and 1970s and still receive taxpayer funds today through Mississippi's education scholarship account program either discriminate against LGBT students, students with common African American hairstyles or pregnant students, or a combination, the Huffington Post reported on Dec. 14.

Each of these schools opened in direct response to court-ordered desegregation of public schools. White parents who did not want their children to attend schools with black children often helped found these academies, many times with assistance from white supremacist organizations like the Citizens Council, which many still refer to as the "White Citizens Council." Famed Mississippi newspaper editor Hodding Carter Jr. called the council the "uptown Klan" due to its membership rolls filled with wealthy white businessman, including in Jackson.

The virulent racist organization, which pushed the bogus "scientific" concept of biological and intellectual black inferiority, started in Mississippi in response to the U.S Supreme Court's Brown vs. Board of Education decision in 1954 and had national influence. Soon based in Jackson, it did not close its doors until 1989 and had immense influence on the re-segregation of Mississippi schools once the high court finally forced public schools to integrate in early 1970 "at once." From 1968 to 1971 and as white resistance to public-school integration failed, the number of Mississippi children in private schools jumped from around 5,000 to about 40,000 and kept rising as white families transferred their kids to segregation academies over the years.

The Huffington Post report by Rebecca Klein is among several substantive pieces examining the segregation-academy phenomenon that emerged in various publications nationwide after this newspaper's report that Hyde-Smith, R-Miss., attended Lawrence County Academy when she was in junior high and high school.

Her stridently segregated school, Lawrence County Academy, opened in 1970 and shut down in the late 1980s, but photos from a yearbook showed Hyde-Smith posing for a group photo with her fellow cheerleaders and a mascot dressed like a Confederate general who held a large Confederate flag as she saluted.

In her New York Times opinion piece, "Cindy Hyde-Smith Is Teaching Us What Segregation Academies Taught Her," Cornell University professor Noliwe Rooks put Hyde-Smith's comment about how she would be on the "front row" of "a public hanging" if one of her constituents invited her in the context of the senator's segregation-academy experience.

Hyde-Smith was not the only person in her family to receive an education at one of those academies. She later sent her daughter, Anna-Michael, to Brookhaven Academy, which also opened as a segregation academy in 1970, the first year of integrated schools in Mississippi when white state officials allowed early vouchers to go to white families to attend the new academies.

Even to this day, Brookhaven Academy—from which her daughter graduated in 2017—is almost all-white. In the 2015-2016 school year, Brookhaven Academy enrolled 386 white children, five Asian children and just one black child, the National Center for Education Statistics shows. That's despite the fact that U.S. Census statistics show Brookhaven is 55 percent black and 43 percent white, per 2016 Census estimates.

'Superior Education,' Questioned

When former Indianola, Miss., Mayor Steve Rosenthal was a senior in high school in 1969, he brought his textbooks home with him for Christmas break and never returned to Indianola public schools. A federal judge had just ordered public schools to integrate immediately, and all black and white high school students were supposed to go to Gentry High School together in January.

Like hundreds of white kids in Indianola, Rosenthal's family instead sent him to Indianola Academy, which opened in anticipation a court order in 1965. Like many segregated academies and "council schools," Rosenthal's new academy did not have large enough facilities for the white students who flooded into it that spring semester.

Instead of a school campus, Rosenthal spent his first semester as an Indianola Academy student at a makeshift satellite campus in a Baptist church, where weekday funerals often interrupted school. Segregation academies, which claimed to be Christian from their outset, have also long provided limited information on scientific concepts such as evolution, the reason for southern secession into the Civil War (slavery) and the full range of American history.

While some white parents have insisted for decades that the purpose of sending their kids to these academies that started as racist shelters for white kids is about getting them a superior education, Rosenthal's story, recounted in a December 2012 story in The Atlantic, suggests otherwise.

The data on the superior education in such schools is mixed, if it even exists. The private academies are backed up with no required public test scores, and they are not plagued with constant testing that many education experts and teachers believe disrupt what students can learn, despite the influx of taxpayer money and efforts to get more.

Lawrence County NAACP President Wesley Bridges told the Jackson Free Press that everyone knew why Lawrence County Academy was set up, and that he believes most white parents who send their kids to private schools today still do so because they don't want them to go to school with black kids.

"A child doesn't have a choice of where their parents send them to school, so she grew up as a child in a private school that was set up so white parents could keep their kids from going to school with African American children, and then sent her child to a private school," Wesley said in November, referring to Hyde-Smith. "This is a broad generalization opinion, but I think 90 percent of the people that send their kids to private schools do it so their kids don't have to go to school with minorities."

Academies Still Mostly White

Rosenthal's story is unique in one important way: He is Jewish and was born into a small Jewish community in Indianola—the birthplace of the racist, anti-Semitic Citizens Council, which raised funds to help white parents send their children to segregation academies.

Today, fewer than 20 percent of Indianola residents are white, but Indianola Academy remains. In 2012, the Headmaster of Indianola Academy told The Atlantic that, nine of the school's more than 400 students were black, and "we also have Hispanic, Indian and Oriental students."

Many people of Asian descent consider "Oriental" a racial slur.

In 2006-2007—the most recent year data are available—just 3.71 percent of students in Indianola public schools were white, and most of those white students are younger students. Parents often move their children to the academy by high school, The Atlantic reported.

Rosenthal, who served as mayor from 2009 to 2014, told Forward, a Jewish publication, that the people in Indianola are "different people now."

His Jewish heritage, he said, helped him develop a different perspective than others might have. "Growing up Jewish gives you a mindset that is so different from the norm," Rosenthal told Forward. "It's our responsibility to make a difference in the world. That's why there were so many Jews that were involved in civil rights in the 1960s —you give the most effort to those who need it the most."

Despite that heritage, though, even Rosenthal did not integrate with Indianola black kids by attending Gentry High School in January 1970. When the school doors opened that spring, in fact, not a single white kid attended Gentry High School.

Email state reporter Ashton Pittman at ashton@jackson freepress.com. Read more on integration and seg academies in Mississippi and the South at jfp.ms/segacademies.

More like this story

- Hyde-Smith Attended All-White ‘Seg Academy’ to Avoid Integration

- The Hunt for Vouchers in Mississippi, After All These Years

- How Integration Failed in Jackson’s Public Schools from 1969 to 2017

- Mississippi School Discriminated to Avoid White Flight, Lawsuit Claims

- OPINION: Cindy Hyde-Smith is Telling You Exactly Who She Is

More stories by this author

- Governor Attempts to Ban Mississippi Abortions, Citing Need to Preserve PPE

- Rep. Palazzo: Rural Hospitals ‘On Brink’ of ‘Collapse,’ Need Relief Amid Pandemic

- Two Mississippi Congressmen Skip Vote on COVID-19 Emergency Response Bill

- 'Do Not Go to Church': Three Forrest County Coronavirus Cases Bring Warnings

- 'An Abortion Desert': Mississippi Women May Feel Effect of Louisiana Case

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.