Corey Wiggins, the executive director of the Mississippi NAACP, called on lawmakers to work to restore voting rights for the more than 218,000 Mississippians who are disenfranchised, at a press conference at the Capitol this session. Photo by Arielle Dreher.

JACKSON — Anthony Witherspoon calls it "divine intervention." Others might call it luck. The second-term mayor of Magnolia, Miss., learned quickly how state laws can disenfranchise and significantly alter a person's life, all depending on what crimes they have committed.

Witherspoon, who is black, was convicted of manslaughter in 1992 after shooting a man "in self-defense" after having six or seven rounds fired at him, he says today. The Mississippi Supreme Court rejected two lower court rulings that he was guilty of murder, and ultimately a jury convicted him of manslaughter, and he drew a 20-year prison sentence. Witherspoon stayed out of prison for four years on an appeal bond and then served six years in state prison.

As soon as he got to prison in 1996, Witherspoon began to research his voting rights, and found that manslaughter is not one of the 22 disenfranchising crimes in Mississippi.

"[I] discovered that ... there were only 10 felonies that disenfranchised someone from their voting rights if convicted of a felony," Witherspoon recalled. "It said murder, but it didn't say my charge, which was manslaughter. It said rape but not aggravated assault."

Witherspoon wrote a letter to the attorney general asking for clarification. The answer was clear: He still had his right to vote. He wrote his circuit clerk and asked for an absentee ballot to be sent to prison. Witherspoon went on to register several other inmates who were eligible to vote as well. Any Mississippian, who is a U.S. citizen and has never been convicted of voter fraud or one of the 22 disenfranchising crimes can register to vote and has the right to vote, including men and women in prison.

"I actually started registering inmates to vote while in prison, and we continued that campaign once I got out of prison," he told the Jackson Free Press.

Witherspoon worked with the ACLU of Mississippi and the NAACP to help educate Mississippians about the specific list of disenfranchising crimes. When Witherspoon got out of prison in 2002, voter registration forms still no disclaimers about disenfranchising crimes, so he worked with the ACLU on an education campaign in order to register more formally incarcerated Mississippians to vote.

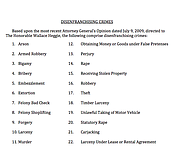

One of the disenfranchising crimes in the 1890 Mississippi Constitution is "theft," which is not currently defined in state law. In 2012, Secretary of State Delbert Hosemann published a list of 22 disenfranchising crimes, based on a 2009 attorney general's opinion.

"Theft" is still on the list, as well as receiving stolen property, timber larceny, unlawful taking of motor vehicle, carjacking and felony shoplifting. Arson, armed robbery, bigamy, murder and robbery also make the list.

Witherspoon's manslaughter conviction also meant he could hold public office, despite not being allowed to get his violent offense expunged. In November 1992, the Legislature had added two exceptions to the law that kept anyone convicted of a felony from running for office: manslaughter and tax violations.

Witherspoon was convicted of manslaughter in November 1992.

"I guarantee that this little country boy did not have that kind of pull with the Legislature, but that's what happened," Witherspoon said.

In the Courtroom

The ACLU of Mississippi attempted to sue the state for its list of disenfranchising crimes when Witherspoon worked there—but did not succeed.

Now, the Mississippi Center for Justice is challenging this list in federal court. Changing the list of disenfranchising crimes could change voter turnout for several counties across the state.

Mississippi is one of 12 states with disenfranchisement laws that can affect people for life. The list of 22 disenfranchising crimes means an estimated 218,181 people in the state are unable to vote, a new study from the Sentencing Project, One Voice and the Mississippi NAACP, shows. In an analysis of 2016 data, researchers found that 93 percent of those disenfranchised on Mississippi's list live in the community—not behind bars.

"Mississippi has one of the most extreme policies. It's one of the states that disenfranchises people for life unless there's intervention either from the governor or from this onerous process where people have to file individual suffrage bills," Nicole Porter with the Sentencing Project told the Jackson Free Press.

Mississippians looking to restore their voting rights must petition the governor for a pardon or executive order or ask their district's lawmakers to introduce a suffrage bill on their behalf, a process that is far from a guarantee. Gov. Phil Bryant has not restored anyone's right to vote during either of his terms and has not signed a single suffrage bill. Suffrage bills, brought by lawmakers on behalf of their constituents, become effective with two-thirds of the Legislature's approval, with or without his signature.

Since 2007, 45 suffrage bills have passed and 83 failed, the Sentencing Project report shows. During Bryant's first and recent term, lawmakers passed 15 suffrage bills.

Some states have automatic voter-rights restoration for people as soon as they leave prison or jail. Maryland just expanded voting rights to people in the community on probation or parole and increased its voter rolls by an estimated 40,000 residents, Porter said. In Mississippi, a similar measure could allow more than 200,000 residents the right to vote again, based on 2016 numbers.

A measure to study disenfranchisement passed the House this year with bipartisan support, and on Monday, Sen. Hob Bryan, D-Amory, passed the bill through the Senate Judiciary B Committee, noting constitutional issues with the list of disenfranchising crimes.

Senate leadership referred House Bill 774to Judiciary B and the Senate Rules Committee. By press time both committees passed the measure, so the full Senate will vote on it in the coming week. Similar measures have died in the Senate in previous years.

A Racist List of Crimes?

Felony disenfranchisement still disproportionately affects African Americans in the state. At a press conference this month, the Mississippi NAACP called on lawmakers to change the state's stringent disenfranchising laws.

"Mississippi's restrictive suffrage laws do not go far enough in providing a meaningful opportunity for enfranchisement," Corey Wiggins, executive director of the Mississippi NAACP, said in a press release.

"To deny people the fundamental right to vote is at odds with ample evidence showing the expansion of voting rights not only leads to safer communities but has widespread public support."

Nearly 16 percent of the black electorate in the state are disenfranchised, the Sentencing Project report found, using 2016 numbers. Disenfranchising crimes were initially targeted along racial lines. In the 15 years following the Civil War, states ramped up disenfranchising crimes, immediately following black men gaining their right to vote.

"The list of crimes that's in our state Constitution was adopted in 1890 because it was thought that black people were more likely than white people to commit these crimes, and this was one of a number of provisions that the constitution of 1890 (had) seeking to make it more difficult for black people to exercise their voting rights," Bryan said Monday.

Just as Jim Crow laws would do well into the 1960s, the point of the disenfranchisement law was to keep black people from voting.

"The motivation for enacting broad felony disenfranchisement laws in this context was clear: preventing newly enfranchised black citizens from exercising political power," Erin Kelley writes in a 2017 Brennan Center report.

Mississippi's disenfranchisement law was used as a model for other states, when it was adopted in the state's 1890 Constitution, and even the state Supreme Court acknowledged the racist ties to disenfranchisement, while upholding the list as constitutional six years later.

"Restrained by the federal constitution from discriminating against the negro race, the convention discriminated against its characteristics and the offenses to which its weaker member were prone. ... Burglary, theft, arson, and obtaining money under false pretenses were declared to be disqualifications [from voting], while robbery and murders, and other crimes in which violence was the principal ingredient, were not," the report states.

Bryan, who is white, said that Alabama had a similar provision in its constitution that the U.S. Supreme Court deemed unconstitutional.

Witherspoon said that during his work with the ACLU of Mississippi he learned that public education was necessary to inform not only inmates but also circuit clerks that going to jail or prison alone is not grounds for losing the right to vote. Today, the disenfranchising crimes are listed on voter-registration forms and online.

"Now it's 22 (disenfranchising crimes). So you know, now it's 12 that have been applied without an act from the Legislature. I don't understand how you can amend the Constitution outside a legislative act, but that's where we are," Witherspoon said.

Email state reporter Arielle Dreher at [email protected] and follow her on Twitter @arielle_amara.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus