A Neshoba County grand jury indicted a 13-year-old boy on armed-robbery charges for allegedly stealing a cell phone. He is now out on $100,000 bond, although police did not recover the alleged BB gun. File Photo

JACKSON — A Neshoba County grand jury has indicted a 13-year-old African American boy on armed-robbery charges, and he is now out on $100,000 bond. He was arrested back in September 2017 for allegedly using a gun to hold up another boy for a cell phone and a dollar, even though authorities likely have not recovered the weapon, which may have been a BB gun.

Melanie Hagood, who is white, told police in Philadelphia, Miss., that someone had approached her son at the bowling alley in the center of town. "The unidentified male subject then pulled a gun on her son and said, 'give me all of your money,'" the police report reads.

"'I only have a dollar and a phone,'" Hagood said her son replied, per the police report.

The youth suspect's family, however, tells a different story. His mother, Felicia Miller, told the Jackson Free Press in September 2017 that the weapon was a BB gun and that police did not have it in their possession. A front-page story published in September 2017 in the Neshoba Democrat, a local paper in Philadelphia, Miss., backs Miller's story up.

"We didn't recover the gun," Philadelphia (Miss.) Police Chief Grant Myers told the Neshoba Democrat in September 2017. "Even if it was a fake gun or a BB gun, you can still be charged with armed robbery if you present it as a real firearm."

Myers could not be reached for comment before press time.

Under Mississippi Law, it does not make a difference what the gun is because it will still be characterized as armed robbery if the alleged victim believes it is a robbery.

Miller also said at least two other boys were with her son and that the weapon in question belonged to one of them. But because her son was the one that a witness identified, he was the one police arrested at school, she said. Witnesses have not been publicly named.

At the time Miller spoke to the Jackson Free Press, her son was being held at the Neshoba County Jail on $10,000 bond, which the family struggled to fund, and he spent at least two nights there. Miller had been out of work and had just begun a new job when her son was arrested.

"He's never been locked up before," Miller said of her son.

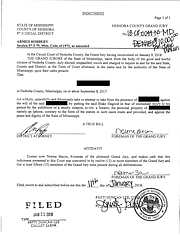

The boy's case went in front of a grand jury in Neshoba County on Jan. 9, and it found that he "did wilfully, unlawfully and feloniously take or attempt to take" a personal property (an iPhone) from Hagood's son and put him in fear of immediate injury by brandishing a deadly weapon (a firearm).

The Neshoba County Jail confirmed that the child was booked there again on Jan. 16 and released later that day. While there, he was placed in solitary confinement because of his age.

Jody Owens II, managing attorney of the Mississippi office of the Southern Poverty Law Center, said one of the worst things you can do it put a child in isolation—they need to be in facilities designed specifically for juveniles, he said.

"People don't realize that isolation is a form of torture," Owens told the Jackson Free Press in an interview this morning. "People don't get healthier when they're isolated that way...how we treat this kid who hasn't been convicted can do just as much harm as if he is convicted."

For certain crimes such as armed robbery, aggravated assault and capital murder, Mississippi law allows youth as young as 13 to be treated as adults in the jurisdiction of circuit court, where a judge can decide if the case would be better handled in the youth-court system. Law enforcement often releases both their names and their mugshots, and even allow media "perp walks" to show them off, even though they are minors and not yet proved guilty of a crime. The Jackson Free Press does not identify children accused of crimes without extenuating circumstances that require it for community safety.

This boy's case is not an isolated incident in a rural county. As of July 2017, the Mississippi Department of Corrections had detained 694 youthful offenders under 22 years old in correctional facilities throughout the state.

It also aligns with a national trend of black youth being more than five times as likely to be detained or committed compared to white youth for the same or lesser crimes, as The Sentencing Project found in 2015.

Research supports that pre-trial publicity for juveniles, regardless of the outcome of the case, can lead to the public stigmatizing them, and potentially leading them to see themselves as a criminal and therefore act like one. "So now you have this merry-go-round here," Patrick Webb, an associate professor of criminal justice at St. Augustine's University, a historically black college in Raleigh, N.C., told the Jackson Free Press late last year.

The JFP's 'Preventing Violence' Series

A full archive of the JFP's "Preventing Violence" series, supported by grants from the Solutions Journalism Network. Photo of Zeakyy Harrington by Imani Khayyam.

"You keep shaping the image through the media," Webb said, "which justifies severe policies and programs in law, which in term feeds into the prison-industrial-complex. And when the stockholders get paid, and they will, then of course they're going to go back to those policymakers through their lobbyists and support their campaigns."

In Webb's studies on the relationship between media coverage and juvenile proceedings, he found that there is an added element of the media flashing teen mugshots, often those of color, to accompany reports of juvenile violent crime.

Media, with full discretion, chooses when they want to run the mugshot of a juvenile being charged as an adult—newsrooms and TV stations are the gatekeepers of the sensationalism that feeds this public demand for safer streets and harsher treatment, Webb's research found.

Email city reporter Ko Bragg at [email protected]. Read the JFP's award-winning archive about youth crime at jfp.ms/preventingviolence.

More like this story

More stories by this author

- City Wants State’s Help Recouping Funds

- Wise Women: A Mother-Daughter Judicial Legacy Continues

- $1 Million Grant from FTA Will Help City Develop Transportation Corridor

- UPDATED: Former JPD Chief Vance Running Against Beleaguered Hinds County Sheriff

- With 84 Homicides in 2018, City Hopes to Stem Violence With New Cops, Strategy

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus