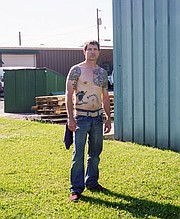

Benny Ivey gets up as early as 4 a.m. to work out in his garage on “Ivey Hill” in Rankin County. He never thought he would have a home, much less a garage. Photo by Imani Khayyam.

"Whenever we yell, y'all come running!"

Benny Ivey's father Glenn had just told him and his brother Danny to hide on the side of their small shack at the bottom of Marsalis Lane in South Jackson.

Benny was 15, and Danny was 16 that night in 1991 as they crouched down, getting ready to ambush a crack dealer who was about to show up any minute. Glenn handed Benny a stick from an oak tree in the yard and Danny a baseball bat.

Marsalis Lane is narrow and hidden on the north side of Raymond Road, a main thoroughfare through a then-booming middle-class neighborhood of Mississippi's capital city. You can miss the tiny lane if you don't know it's there, sandwiched like an alley between two busier residential streets.

When you turn on the one-lane strip of pavement, you immediately drop down a roller-coaster hill with heavy brush and trees on either side. It can look shaded and depressing even on sunny days, a hermetic little world just hundreds of yards from heavy east-west traffic.

The geographically large, diffused and economically devastated city has many such ignored grassy pockets that can attract crime, debauchery, piles of garbage, and abandoned cars and lives.

The men in the white family, all long addicted to various substances as their parents had been, had graduated to crack by the 1990s as the drug was destroying the lives of various races all around them. Patsy, the woman Benny considered his mother although she was his biological aunt, had also moved to crack from her addiction to Dilaudid and other powerful opioids.

The family needed more of the seductive "candy," but didn't have the money to buy it just then. Benny's father worked as a carpenter for $20 an hour, but it all went to support their habits and ran out fast. So they cooked up a scheme to get a black woman crack dealer Glenn knew to bring them some rocks, and they would rob her and take all the product she had on her.

'I Just Want to Thank You for Not Killing Me'

As the boys waited excitedly with their sticks at the bottom of Marsalis Lane, they could see headlights creeping down the hill toward the shack at the bottom, where the open porch was their bedroom. They could see the woman, but she was in the passenger seat. The dealer she worked for was driving. He was also black.

The duo pulled up in front of the house, and the plan unfolded. Danny's girlfriend had an old hatchback Chevette that was broken down and parked adjacent to the driveway. When the dealer turned in to park, the adult men pushed the old car behind him real fast so he couldn't back up, setting the trap.

They yelled for the boys, and the ambush started. The Ivey youngsters broke out the back glass out of the visitors' car to stun them so they didn't know who all was holed up down there on Marsalis Lane. Glenn slung the passenger's side open and stabbed the lady dealer in the leg. Uncle Jackie opened the driver's door and put a knife to the man's throat.

The white mob terrified the victims, who didn't try to fight back.

The Ivey men then pushed the Chevette out of the way of the dealer's car, and the driver slammed the car into reverse and gunned it up the hill backward.

"I ain't never seen anybody go so fast in reverse," Benny Ivey said in November 2017 while sitting on Marsalis Lane in front of the spot where the shack, long fallen down, used to stand. "They never turned the car around. They come all the way up this little hill in reverse."

Inside the rental house, the mob was mad and cussing because they only got two rocks out of the ruckus.

Then, the wall phone rang, and Glenn answered it. It was the crack-dealer lady.

"What do you want?" he asked.

"Glenn, I just want to thank you for not killing me," she said. "There's some rocks outside by the tree in the front yard."

He hung up and went outside to the oak tree, and sure enough, there was a paper bag full of crack that one of them threw out of the car when they heard people yelling and running their way.

The adults in the Ivey family smoked a long time on that supply. Benny and his brother didn't, though. By then, they had dropped out of school and were developing their own addiction to meth, which Benny would prefer to cocaine for many years to come.

At that point, the teenagers were also helping the adults bust into houses all over South Jackson in order to fund the family's menu of addictions.

Benny Ivey believes now that he kicked in doors to 200 houses during those years, often with his uncles, during the day after people had left for work.

After telling the crack-heist story in late 2017, Benny was silent, as was his wife, Kristina, as we pulled slowly back up the hill away from the creepy inglenook toward the real world of Raymond Road.

"Take a right, baby," he finally said to his wife, who was pulling the SUV up to the stop sign at the top of the hill.

Then, to all of us: "That's how I was raised, you know what I mean?"

AWOL and Joyriding

Benny Ivey's older buddy, Chris Dennington, picked him up in his primer-black 1969 Nova one day in 1991, and they soon were speeding around the Jackson metro, drinking beer and joyriding.

Dennington had bought the car for $300. It didn't have any carpet, but it had "plugs" in the floorboard that opened to the street below. They liked to throw their trash out through the holes.

Both blond Wingfield High School dropouts—Dennington had just turned 18, and Ivey was still 15—had pistols on them from previous house burglaries on the Jackson metro's "Southside," which for young white criminals spanned from South Jackson, where many then grew up, east into suburban Rankin County, where many eventually moved as demographics shifted. Poorer families like Ivey's moved back and forth across the county line chasing the next place they could afford after an eviction or a new place to hide out.

The teenagers had left the Ross Barnett Reservoir before they headed down Highway 49 South, with Ivey popping open beers for them along the way. He and Dennington had met as cellmates in the Hinds County Juvenile Detention Center, then on Silas Brown Street in downtown Jackson, where they both went after being busted for house burglary.

In the lonely facility, the teenagers liked to sing songs from Boyz II Men to Skid Row, and they would watch "DuckTales" and other cartoons. When there was trouble, they were locked down in the cell for 23-hour days.

Both stayed in detention several months before Ivey was sent to the Oakley training school, a rough facility for minors in Raymond that was formerly known as the Negro Juvenile Reformatory and then the Black Juvenile Reformatory School before it became a still-abusive facility for teenage boys of all races by the time Ivey was there.

When the joyride down Highway 49 started that day, Ivey was supposed to be back at Oakley after visiting his mom, but he decided to go AWOL instead.

'Boy, How Old Are You?'

When Ivey and Dennington stopped at a red light in front of a Richland Conoco, police suddenly flashed blue lights on them. They had marijuana in the Nova, as well as their guns and a case of beer.

"Oh, man, I'm going back to training school," Ivey cried out when he saw the flashing lights behind them.

"Naw, you're not," Dennington said, punching the gas. The speedometer lurched toward 100 as the police chased them south through Richland. Along the way, the young men stuffed the weed and the guns through the plugs in the floor.

Soon, Dennington slammed on his brakes to take a hard left onto Star Road, and the cops flew past them. They turned on another road to get away, but suddenly, it was "lit up like Christmas up ahead" with a roadblock, to use Ivey's words.

The cops came up with guns drawn, snatched the duo out of the car and threw them face-down on the ground. One of the officers kick-stomped Ivey in the back of the head, busting his chin open, while another hit Dennington in the back of his head with the butt of a shotgun, he says. The cops then picked the teenagers up and slammed them on the Nova to cuff them.

Another officer ran up. "Hold on, stop! Boy, how old are you?" he asked Ivey.

"15."

"Put him in the car and take him to the precinct," the officer ordered the cop who had kicked Ivey.

An ambulance was waiting at the police station, and a paramedic cleaned up their wounds and the blood. In the meantime, they could hear cops on the radio: "We found a gun."

The cop said it had bounced from under the car and busted out a headlight on his squad car. They'd also found a piece of the second handgun but couldn't lift fingerprints off the gun parts.

They arrested Dennington for multiple charges. They didn't charge Ivey, perhaps because of the boot to the back of the head to a minor, instead taking him back to South Jackson and dropping him off at the same apartment in Choctaw Village where he had recently done meth—and liked it—for the first time with Dennington. They did alert the Jackson police, however, and they picked Ivey up the next morning and took him back to training school.

"That was the start of it," Dennington said at his brother's home in Fondren in early May 2018, just two weeks after he left his last bid at the maximum-security Wilkinson County Correctional Center.

Over the 27 years since the Rankin joyride, Dennington has spent 24 years total in prison, and Ivey 10 years. They both joined white gangs in prison —the Simon City Royals for Ivey and the Aryan Brotherhood for Dennington and, eventually, Ivey's brother Danny.

Gang life was about both brotherhood and staying alive, depending on the day. But the drugs had a far worse pull on them and others around them than either gang did. Pledging loyalty to a gang was a symptom of a more daunting reality—addiction.

'The Devil in Your Brain'

By the time the high-speed chase started in 1991, the Ivey brothers and Dennington were speeding down the road to destruction, fueled by substance addiction. Ivey started out sniffing Scotchguard when he was 13, soon starting to smoke weed with his dad and uncles, and then getting hooked on meth.

Dennington, who was closer to Danny Ivey then Benny, helped himself from his mother's supply of diet pills when he was 13 or 14. He graduated from pot and meth to crack before he turned 18. But his worst deeds came while strung out on Xanax over the decades.

South Jackson was a hotbed of drug activity when these young men and their friends came of age in the 1980s and '90s. Just about two decades after the U.S. Supreme Court forced white schools there, like the shining new Wingfield, to allow black children to attend in early 1970, the area was still majority-white. And many young white people were strung out on one drug or another, committing crimes to support the habits, and craving the gang life.

Solutions: How to Prevent Gun Violence

Evidence-based programs that can help prevent and reduce community gun violence

Dennington's family had moved back to the neighborhood where he was born at the old Baptist Hospital after their house in Brandon burned down. When he met Danny and then his brother Benny when locked up, Dennington was living in an apartment in Choctaw Village, and his father had a flooring business.

He blames all the "hoodlums" he grew up around in South Jackson—white kids getting high, robbing and stealing to pay for the drugs they were consuming.

It was one crime after the other for Dennington—each seemingly crazier than the last. He would get out of detention or jail and immediately rob again to feed his habit. He helped hold up crack dealers in "cracktown" (then Gallatin Street south of Interstate 20 near the present-day juvenile-detention center). He stole jewelry from South Jackson homes, one time robbing a house while the mother was sleeping on the sofa, her daughter outside twirling a baton. He used a mop while standing outside an open window to drag jewelry off the counter. He and Danny also stole a car and took it on a joyride to Florida.

Dennington became Aryan Brotherhood in Parchman prison when he was 19, he said, because his unit didn't have many white guys, and he desperately needed protection. Many prison gangs are race-based, although some like the Simon City Royals are also allied with black and Hispanic gangs.

AB, however, prides itself on its white supremacy, with tattoos such as swastikas. Dennington says that most guys don't join because they're racist, though; they are lured to the need for security in prison, he says, and often do not realize the true ideology until later.

The drugs made him commit the crimes, Dennington explained in early May 2018.

"It puts the devil in your brain and steals your brain. You don't think," he said of addiction.

'Raised in the Pits'

Benny Ivey preferred meth over powder or crack cocaine and can still describe the euphoric high it gave. Meth made a high-energy guy even more so. Over the next several years, he kept getting high and started selling, and sometimes cooking, meth himself to support his own habit.

Ivey's life was mostly on the streets, interacting regularly with black and white drug users, dealers and thieves just as his elders had done. "We don't all have trust funds and 'privilege,'" Ivey said in April 2018. "There are a lot of us that were raised in the pits, and that's where almost all gang life begins, no matter the race or gender."

Like many of the young black men Ivey got to know on the streets and while locked up, no one either in the system or on the outside tried or seemed to know how to help him choose a different route than crime. It was just assumed that his life was worthless and hopeless.

By then, Ivey's parents were fully beholden to their crack addictions. He had been on the honor roll until middle school, he says, and he was talented, even helping lead a rock band called Silent Threat for a while.

Ivey was and is funny and personable, but had no sense he could become more than his parents or escape the hamster wheel that is generational poverty that, in turn, too often leads to addiction.

He had no mentors, no former criminals trying to tell him to do right, no nonprofit trying to get him back into school or to work on his GED. Ivey once had good grades, but that had gone to hell after his early gang obsession—South Jackson white kids pretended to be members of the Vice Lords and the Black Gangster Disciples during the crack era—and his tasting drugs for the first time. An actual job wasn't something he considered, nor even getting a driver's license. He wouldn't have known how.

Life in the Ivey household was constant parties and cookouts, bouncing from the highs to the lows of addiction, and then back again.

Ivey did have some carpentry skills his father had taught him when he was a kid, and he would pick up a day construction gig here or there, but like his father, he used the money mostly for drugs.

His and Danny's only respite, when they had nothing to eat or no bed that night, was to go to their Aunt Peggy's house, in a brick rancher in South Jackson that he still points to fondly while driving by it long past her death. There, the boys would watch their uncle, Russell, pass out every night in his recliner in an opioid haze.

Along with Dennington, his brother and many like them, Benny Ivey was a kid without a future. No one could, or would, do anything to change that for many years.

Only Black People Prosecuted Under Mississippi Gang Law Since 2010

Mississippi legislators like Republican Sen. Brice Wiggins point to growing white gangs to push for tougher gang laws. But there's a problem.

On a driving tour of his old haunts in November 2017, Ivey pointed to a house on Paden Street, near the Southside Assembly of God church, where he had kicked the door in and robbed it one day.

It was the house burglary—out of around 200—that got him sent to the juvenile detention center and then the Columbia training school, back before lawsuits led to reform of the abuse-filled facilities with putrid conditions.

"That was horrible as a kid, you know what I mean?" he says from the passenger's seat about juvenile detention. The youth facilities provided no real education, counseling, mentoring or efforts at rehabilitation then, just as prison never would later.

"Naw, nothing," Ivey said on the driving tour, shaking his head.

'That's My Homeboys'

Benny Ivey faced increasing trauma through his teenage years in the 1990s as his meth addiction and the burglaries he committed to feed it kept him spiraling through a dark abyss that juvenile detention and training school—that brought no actual training—made worse. By 1997, he was 21 and living in a South Jackson rental off Old McDowell Road Extension with his young first wife and other meth heads.

One of them was his best friend Jimmy, who one day decided to kill himself with Ivey's gun, right in front of him. Ivey lost any remaining control after that. After he was charged with aggravated assault for "punkin'-heading" a man at a party, breaking his jaw, and then more robberies, Ivey went to the Hinds County Jail before moving to prison.

There, he met a member of the Simon City Royals who called himself "True Love."

When Ivey met True Love and friends in jail in 1998, he was relieved to discover a white brotherhood that understood a "redneck" like him—his word—and would have his back. His mother didn't have transportation to visit, and he was alone behind bars. "That's my homeboys; that's the people I'm gonna be around," Ivey said he believed then.

The Royals, a national street gang that originated in Chicago in the 1950s and has grown in Rankin County and Mississippi in recent decades, convinced Ivey they could improve his life. Like many, he was attracted to the gang from an unstructured life without positive adult influences.

"It was about bettering yourself: get a job, go to school, learn communication skills so you can do anything, go to banks, get loans," he said. "Most getting into gangs didn't come from environments to know how to write a check, or basic life skills."

After several months, Ivey was moved to the neighboring Rankin County jail to be processed, alongside True Love and friends, for prison on the burglary charge. By then, he had learned that the Royals were allied with the storied Black Gangster Disciples, another Chicago gang originally started by Larry Hoover, a man born here in Jackson, Miss., who as a toddler had migrated north with his parents as they sought a better life.

Never Back Down: Mississippi Escalates War on Gangs

A proposed gang bill was not based on current evidence-based violence research. It died in the Legislature.

As guards watched in the jail, Ivey says, allied Gangster Disciples and Royals moved to one side of the communal zone, and several held up a sheet to block the view. "They knew we were doing something illegal and didn't say nothin'," he said of the guards.

The gangsters backed Ivey into a wall. He vowed loyalty "to the death" and to keep Royals rules confidential. Gangsters punched him hard in the chest 12 times—called "catching the gap." They then pricked his finger, and he bled on a "birth certificate" with the six-point star the Royals inherited from the Gangster Disciples after joining the Folk Nation alliance in Chicago in 1978.

Getting "blessed in" to a gang, as Ivey calls it, is not only the initiation, but the mindset of new members like him who were finally part of something bigger than their miserable lives. Gang members do not usually step down to the life from a structured reality with positive adult influences. They tend to step up into the group from the depths of trauma or abandonment—like watching parents smoke crack or your best friend blow his head off with your gun.

The first day after Ivey—"Outcast" to the Royals—arrived at the South Mississippi Correctional Institution, he helped the Gangster Disciples. "I wasn't there five minutes, and I had to put my boots on and hold security ... so they could beat the dog crap out of their guy," he says of a GD who had ratted to the cops.

The Greene County prison, he says, was filled with gangsters protecting their own and their allies. Behind bars, it takes a village to stay alive and avoid physical and sexual assault. "We called it the Thunderdome, because it was gangbangin' every day," Ivey said.

Ivey also did illicit drugs every day in prison.

Like him, many members suffered from addictions or were the children of addicts, including alcoholics, living life day-to-day, from one high to another.

Organizing Mississippi's Royal Nation

During that two-year bid and soon another two at Parchman for violating probation, Ivey took the title of Central Mississippi regional captain of the Simon City Royals and then returned home to organize Mississippi's Royal nation from Rankin County.

"In 2003, there was no structure, no meetings—was none of that on the streets of Jackson or in Mississippi," Ivey said. "I was going around trying to bless people in."

That is, he wanted to initiate others into the supportive group he had found. "I didn't become Royal because I wanted to sell dope, run the streets. That was the farthest thing from my mind," he said. "It was the structure thing, the brotherhood. I had their backs, they had mine, no matter what."

Ivey's Royals didn't sell dope as an organization, he said, although many of them sold it to support their own addictions, as he certainly did.

The Rise of America's White Gangs

Donna Ladd reports for The Guardian on the largely ignored rise of white gangs in America, and how they're treated differently from black and Latino gangs. Photo: Imani Khayyam

By 2008, Ivey ran the gang from Rankin County trailer park where a mother of two called "Spirit"—Thomasa Massey—lived and helped run gang operations. She helped administer the Royals' fund; each member would put $6 a week in and could borrow if they needed a child-support payment or to keep their lights on. If they did not repay the money, or violated other rules, other Royals could "smash" (beat) them.

Ivey strongly believed then that his members needed family gatherings. His first outdoor rally of Royals was in May 2008 at the Barnett Reservoir north of Jackson, but he moved it south after the mostly white and well-to-do population up there complained. Later, he hosted an even bigger gathering in a West Jackson parking lot. An old photo shows about 150 white men, and a few women, with Ivey beaming front and center. They drank beer and did business.

Some Royals were tagging property over in Rankin County. "We had to address that. Stop that," Ivey says. He made two members who had jumped a guy in a bar each fight two brothers at the same time as punishment.

But Ivey's newfound family would not last. By late 2008, some of his members were beefing, which turned into violence—most gang violence in the U.S. today is between members of the same group, experts say—and some were talking to the feds. Law enforcement led a big bust of the gang in Rankin County, sticking many of them with $1 million bonds, although not Ivey.

"When all that happened, everybody got scared to even be seen around each other," Ivey says. Then 32, his ERS—freedom due to "earned release"—was revoked due to gang activity, and he was sent to the private Delta Correctional Facility, which was notorious for gang activity and violence. There, he gathered Royals in the yard and told them the feds were after him.

"I have to retire, because I'm a liability," he said.

Ivey had his six-point tattoos covered, but left the large Royal shield on his shin, inking "retired" under it.

"It was all a blessing in disguise," he says now. "When it all went down at first, I was heartbroken. I thought I was doing something. I wasn't doing nothing but prolonging my miserable existence."

'Addicted to the Lifestyle'

In 2006, Randy Adams was sitting in a waiting room with his life flashing in front of his eyes when an angel appeared next to him.

Then 39, Adams was facing 30 years in prison for dealing meth. The Pearl, Miss., native had worked as a truck driver since he was about 20, soon doing the drug to help him stay awake on long hauls between Mississippi and California. He had been smoking pot since his early teens, so illicit substances weren't new to him.

Adams soon started buying meth in California and bringing it back to his home state to deal even as his first wife and three daughters waited at home.

"I was selling to support my habit," Adams, now 51, said in May 2018 sitting on the deck behind his large brick home in South Jackson. He got away with it for years, but was finally caught up in an undercover sting, bolstered by audio and video from a truck stop. He was changed with transfer of controlled substance.

While he was in the Hinds County Detention Center, Adams attended Narcotics Anonymous and Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. But he was sitting outside the courtroom awaiting his sentencing when that angel appeared in the form of Brenda Mathis, program director of the Hinds County Circuit Drug Court.

Without Adams knowing who she was, Mathis just started talking to him, and he told her his whole story. She must've liked what she heard because she soon asked if he wanted to attend drug court instead of getting locked up.

Hinds County Circuit Judge William Skinner approved, and Adams got out of jail. Deputies took him to Common Bond Recovery Center, then a drug-rehabilitation center in South Jackson, in shackles and chains. He was under court order to complete 30 days of treatment.

At the point Adams could leave Common Bond, though, he decided to stay longer. "That's when things really started changing," he said.

Because the counseling was so effective, Adams started studying it himself. He went on to get a degree in counseling from Jackson State University, and Common Bond then hired him as a counselor. He worked his way up to admission director and then executive director, wanting to help others like himself.

At his home, Adams knocked on his own chest, choked up. "That's where my passion, my heart was," he said.

The first time Adams met Benny Ivey was in the Rankin County Jail in 2010. Ivey had left Delta Correctional not a gangster, but still an addict. He soon got busted again for driving a woman to a drug deal (which he says he didn't know was happening). At that point, Ivey was 34 and sitting in jail in a state of despair, sick of his years of crime and addiction, but with no idea how to leave it. He had never even had a driver's license, much less a real job.

"They'd never tried to get me to rehab, they always sent me to prison," Ivey said in late 2017. "... All I knew was dope and gangs, that's all I ever cared about. But I was tired of it, man."

A friend told him about Common Bond, and he asked to talk to them.

Adams remembers first meeting Ivey in the jail and how disgusted he was with his own life choices, as Ivey broke down crying in front of him: "He wanted to change, but he didn't know how." Adams told the cops he wanted Ivey in his rehab to change his environment and "to give him a helping hand instead of handouts."

At Common Bond, Ivey worked out, prayed, and wrote his story with pen and paper for eight months, as he remembered while standing in the parking lot pointing to now-boarded-up buildings of the rehab that had changed his life.

It later closed due to lack of funding, Adams said.

Ivey also met his now-wife, then Kristina Arnold, at the rehab facility as she was visiting someone else. He used his charm on her; she by then was a former addict herself, and she had a young daughter and was suspicious of his past. But when Ivey got out in 2012 with all charges dropped, they moved in together, and he landed his first real job—re-grouting floors and clearing sewer drains for $10 an hour, working day and night.

He and Kristina soon got married, and he adopted her daughter, now 12, on Valentine's Day 2013.

Ivey's trajectory had definitely shifted upward since Common Bond: He became a partner in the plumbing business when one of the partners died, lifting his income. And the couple found a 2,100-square-foot home on what he now calls "Ivey Hill" near Florence in rural Rankin County. It was a mess, but he used remodeling skills his father had taught him to fix it up. He now uses it for cookouts, especially on NASCAR days, and he'll drink a Corona or two, but does no drugs.

He and Kristina work out in the garage where he used to have a Confederate flag on the wall—as a sign of rebellion against Yankees who belittle southerners, he said—until photographer Imani Khayyam, who is black, visited with me. "I didn't want to hurt Imani," he told me later. "The flag is not about racism to me."

It's Starting All Over'

Since I published a story about Ivey and white gangs in The Guardian in April 2018, his life has made yet another turn. Due to his life of crime, Ivey has longed to be what is commonly called a "credible messenger" in the violence-prevention world—although he was not familiar with the phrase. He wanted to use his story and experiences to deter young people from making the same mistakes.

And now it is happening: He is visiting detainees at the Rankin County Juvenile Center every Thursday; he speaks to young people of all races at the training school that he fled as a teenager; and he would soon become one of the first two official credible messengers in Mississippi.

That, in itself, is fairly unusual; it is rare to meet white credible messengers and violence interrupters in a country where people tend to see black or brown when they hear the word "gang."

Ivey is determined to cross race lines to help deter crime, especially since he grew up knowing that the same forces can lead to crime across race lines, especially poverty and addiction. He and Kristina showed up at Jackson City Hall in early June 2018 for a meeting about crime, telling his story about stabbing the crack dealer on Marsalis Lane to a mostly black audience. He also met with A.T. Mitchell, who leads anti-violence work in New York City and whom Mayor Chokwe A. Lumumba had invited to Jackson to consult on crime issues.

Ivey started networking with Ronnie Crudup Jr., who runs New Horizons Ministries in now-majority-black South Jackson, to help assemble a group of multiracial credible messengers, drawing on gang members Ivey has known over the years in prison and on the streets: Royals, Gangster Disciples, Vice Lords, Latin Kings and even Aryan Brotherhood.

Facebook is a pulpit for Ivey's ministry, drawing comments from former gang members who are cheering him on and telling him to hurry and publish his damn book because they'll buy it. On June 20, 2018, Ivey posted that he had run into a former Aryan Brotherhood member who told him, "Yeah, I don't associate anymore, but I'm still white."

Ivey answered, "I don't associate with Royal anymore either. And Jesus wasn't white, so I don't care nothin' about race."

Ivey then added: "Don't come at me with nothing resembling racism or hate. I don't wanna hear it lol." (He types "lol" a lot.)

At the June 2018 people's assembly at New Horizon Church on Ellis Avenue in his old Jackson neighborhood, Ivey was one of a few white faces in the packed room of people brainstorming solutions to crime and violence. He sat with John Knight, a long-time Vice Lord and drug dealer in the Washington Addition who spent 9.5 years in prison and has tried to organize young people who have been in trouble against crime.

Sitting in the circle, the loquacious duo of Ivey and Knight discussed what people need when they leave prison to keep from re-offending with people who had never been on the inside. They sat arm-to-arm, using colored markers to earnestly fill big stickies with suggestions. Then they stood together to report out to the group.

The JFP's 'Preventing Violence' Series

A full archive of the JFP's "Preventing Violence" series, supported by grants from the Solutions Journalism Network. Photo of Zeakyy Harrington by Imani Khayyam.

"Trade classes before release. Integrate into society with sponsored employers," Ivey suggested. "... Transition meetings to go to upon release ... kind of like AA meetings so you're around like-minded people who can also ..."

Knight, a black man who stands about a foot taller than Ivey, jumped in to finish his sentence: "... better acquaint you from coming from incarceration back to society. Know what route you need to take, what you need to go to to make yourself a whole person again."

"You have to not think about catching up," Knight, now 41, added as Ivey listened, nodding. "Most of the time, it's starting all over. Some people have nothing, nobody to encourage them to know that life's not over."

Meantime, Chris Dennington is determined to do the right thing and stay out of trouble. He is working in his brother's restaurant in Pearl, while building his own remodeling business. Dennington also wants to help steer young people away from crime and addiction as well, and hopes to work with Ivey's credible-messenger team to tell his story and inspire others to make better choices.

Dennington's message is straightforward: "I hope society will forgive us."

NOTE: Since this story first published, Benny Ivey was selected was one of the first two official credible messengers in Mississippi in a new program in Jackson. That is added to the story above.

CORRECTION: The print edition reports that heroin was among the drugs that Chris Dennington used. That is incorrect, and the writer apologizes for the error.

Read more about Benny Ivey and white gangs in Donna Ladd's article for The Guardian and John Knight in the JFP's "A Hunger to Live" story.

More like this story

More stories by this author

- EDITOR'S NOTE: 19 Years of Love, Hope, Miss S, Dr. S and Never, Ever Giving Up

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Systemic Racism Created Jackson’s Violence; More Policing Cannot Stop It

- Rest in Peace, Ronni Mott: Your Journalism Saved Lives. This I Know.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Rest Well, Gov. Winter. We Will Keep Your Fire Burning.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Truth and Journalism on the Front Lines of COVID-19

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.