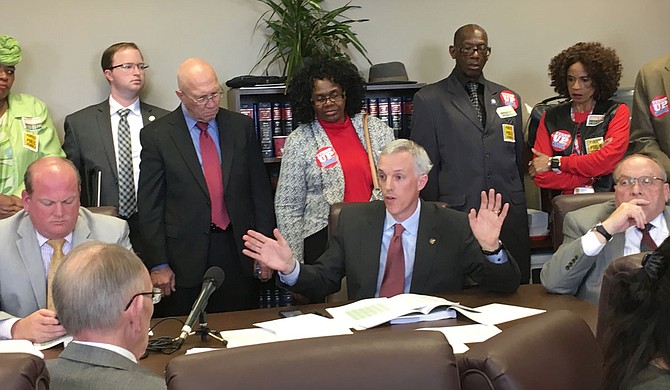

Sen. David Blount, D-Jackson, (center) spoke against the Uniform Per Student Funding Formula proposal in the Senate Education Committee in February, debunking the idea that the bill has been available to the public for a year. Photo by Arielle Dreher.

"You should be happy," Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves said, clapping veteran Daily Journal reporter Bobby Harrison on the back as he descended testily from the Senate dais.

It was just after the effort to replace the Mississippi Adequate Education Program with a new formula failed, and the Senate buzzed in astonishment. Reporters were stunned. Reeves, a Republican from Flowood who hopes to be the next governor, seemed to be laughing, likely in reaction to one of the first times in recent Senate history that the leader allowed senators to consider a major bill without having enough votes secured to pass it.

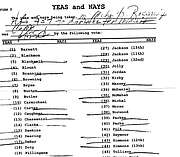

Twenty-six senators joined Sen. Hob Bryan, D-Amory, to kill the Republican-driven proposal to scrap MAEP, which would have replaced it with a weights-based student funding formula, which EdBuild developed and GOP leaders cherry-picked. Eight Republicans broke with leadership and voted with all the Senate Democrats (also a rare block vote) to kill the measure.

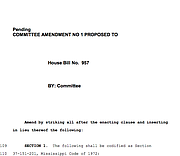

Sen. Gray Tollison, an Oxford Republican who flipped from the Democratic Party after winning re-election in 2011, thought the vote would be close but that he had enough support to pass House Bill 957. Senate leadership was clearly confident about their impending victory because it went to the floor for a vote nearly a week before the deadline to pass legislation.

Bryan was not confident about his vote count to stop it, however.

"I think there were about 10 votes that could have gone either way," he told the Jackson Free Press later. "I think the more people that looked at it and the more people that kept coming to us and saying, 'it's got problems,' the better we felt."

The debate had lasted an hour. Tollison outlined the legislation and took a few questions from Republican senators. Then the chamber got oddly quiet. Bryan stood to raise a motion to recommit the bill to committee. His motion took precedence over Tollison explaining the proposed amended version of the House proposal to rewrite the education funding formula.

"I would suggest to you that the appropriate thing for us to do is recommit the bill to the education committee," Bryan said. "... If they can produce a piece of legislation which addresses all the concerns folks have, ... there are ways to get that legislation passed. ... But we don't need to be making this decision now."

Bryan, a long-time senator and original author of MAEP, did not get loud or excited and kept his voice steady as he explained his reasoning for wanting to kill the measure. He pointed to discrepancies in data. It was difficult to find someone who could explain exactly why the numbers seemed to be off, specifically with special education and vocational and technical education and English language learners, Bryan told the Senate.

Twice, senators agreed through a voice vote to allow Bryan to continue explaining his motion, the first sign that perhaps not all Republican senators were ready to bend to Reeves' will.

Tollison responded with fire in his voice. He clarified for senators that Bryan's motion would kill the bill and sought to address some questions about the legislation, including why certain weights were included for certain students, like English language learners, gifted and special education students. Tollison said some school districts are not reporting how many English language learners they have because they get "zero" state dollars.

"If we put a weight in there for state money, guess what? They are going to start reporting it. Let me be clear about this, EdBuild doesn't determine how much money goes to our school districts, the state Department of Education will do that," Tollison warned fellow senators.

Bryan came forward once more to defend his motion, getting to the larger issue most Democrats had with the bill.

"I have shown you and passed out what MAEP would be six years from now, and what this formula does six years from now. Accepting what the chairman is saying, one-quarter of the districts will get less state money six years from now than they are getting right now, assuming enrollment is constant," he said. "... Do you think one quarter of the school districts in this state are getting too much money?"

The Senate clerk took a roll-call vote on Bryan's motion to kill the bill. Several Republicans voted "yea" with all Democrats. Reeves read off the final tally.

"By a vote of 27 yeas, 21 nays, the motion passes," he announced.

Someone in the chamber let out a "Woo!" while onlookers buzzed in shock.

What Happened?

Kelly Riley, executive director of the Association of Mississippi Professional Educators, thinks lawmakers were listening to their constituents back home.

"Today was an affirmation of the democratic process," Riley said last week.

Sen. Chad McMahan, a Republican from Guntown, said that while he supported a simpler funding formula, he had an obligation to vote the way his district wanted him to.

"Literally, I had not one phone call for me to support this particular bill because it was a large bill that was misunderstood ... in my district," McMahan said after the vote. "... Ultimately, I'm here to support what my district asks of me, so I did what my district asked me to do."

Thirty-five school districts would lose funding under the new proposed funding formula, and some senators and representatives voted accordingly. Sen. Briggs Hopson, R-Vicksburg, for example, voted to kill the measure. The Vicksburg-Warren School District, for which he serves as board attorney, would lose more than $1 million comparing the new formula at full funding to MAEP funding from last year.

Riley said a majority of her members did not support the proposal and called their elected officials to tell them so.

Mississippi Professional Educators has more than 10,000 teachers, administrative staff, superintendents and school support staff like program managers and bus drivers throughout the state, as members.

UPS vs. MAEP

Several educators and superintendents had legitimate concerns about the proposed the Mississippi Uniform Per Student Funding Formula, especially how the new formula would change the mechanics and ultimate results of MAEP.

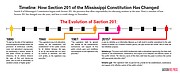

MAEP re-calculates the base student cost every four years. The base student cost calculation is based on an evaluation of expenditures needed to operate at "C"-rated districts throughout the state. MAEP uses the base student cost, which is adjusted for inflation, in its formula to determine the total amount of funds school districts need to operate as defined by "adequate" districts in the state. The Mississippi Department of Education requests this number each year in its budget but rarely gets that total.

Joyce Helmick, the president of the Mississippi Association of Educators, explains that MAEP is the total amount of funds needed to operate "adequate" schools, not pay to create excellent ones.

"This is not funding for schools to be top-of-the-line; this is funding for average schools," she told the Jackson Free Press. "But if you underfund for average schools, you're expecting lower-than-average schools; yet they want the schools to all be "A" (and) "B" schools. That is totally illogical thinking. If I want my team to be winners, I have to provide them with the equipment and the space and time they need and everything they need to be winners."

Districts currently get MAEP funds as one big check that they can use on whatever they need. The proposed UPS formula would not have changed this practice, especially in light of the Mississippi Supreme Court's ruling that the Legislature is not required to fully fund MAEP.

Lt. Gov. Reeves said last week that MAEP is just "a way to distribute funds."

"When the Supreme Court ruled that the Legislature will decide on a year-to-year basis how to appropriate funds and how much money is going to go to schools, they basically threw out this whole funding formula except for the fact that it's a way to distribute funds," Reeves said. "What was voted on today was a different way to distribute funds—I would argue a significantly better way."

The weighted formula would enable lawmakers to apply a base student cost in order to fit the budget available or the budget they want to spend on education in any year. Riley said Rep. Rob Roberson, R-Starkville, told teachers at a conference in Jackson last month that the new formula would enable lawmakers to fund education according to the budget lawmakers had available. This is a shift away from MAEP, which produces a number based on what schools need—not what lawmakers want to or can afford to fund.

The UPS formula is largely the brainchild of House Speaker Philip Gunn, R-Clinton, who worked to put EdBuild's 80 pages of recommendations into a bill form. House Education Chairman Rep. Richard Bennett, R-Long Beach, told reporters in January that MAEP is not a realistic formula, noting that the Legislature has only fully funded it twice since passing it in 1997. Democrats counter that if Republicans had not cut taxes, the funds would be much closer to meeting full funding.

Or as Harrison wrote in an opinion piece in late February in the Daily Journal, likely to Reeves' chagrin, "If not for the more than $300 million in tax cuts that have gone into effect during the past six years and the more than $400 million in tax cuts that will be enacted in the next eight years, the state could afford the full funding of the Adequate Education Program."

Overall, the UPS formula calls for more than $200 million less than MAEP calls for at full funding. Both formulas include measures that mean fewer students or losing students means losing funds.

Reeves told reporters that Democrats want to hold on to a "political tool" with MAEP, but several teachers and public-education workers see it differently.

"Our position has been more on the Legislature's unwillingness to fully fund the formula. We have consistently supported full funding," Riley said.

On Equity and '27 Percent'

While the UPS formula is dead this session, it is far from gone.

"I think this is part of that puzzle of education reform in our state," Sen. Tollison said last week.

He said that in order to put more funding into education going forward, lawmakers will need to adopt the new formula. The Senate leadership advocated for the new formula because it increases funding for low-income students. The EdBuild proposal directs more than $100 million to low-income students than MAEP does currently, but it significantly changes how those students are defined in state law.

Currently, a district is allocated at-risk funds in MAEP for students who receive free-and-reduced lunch from the federal government, but in poor Mississippi, that number is high, with 70 percent of students receiving additional financial assistance from the state, valued at about $268 per student, EdBuild estimated in their report.

The EdBuild proposal instead tried to target the most-needy students in the state, which would have shifted funds to fewer districts for low-income students at about $1,000 per low-income student—ideally to have a greater impact. EdBuild suggested using U.S. Census Bureau small area income poverty estimates to determine a district's low-income weight.

"If you look at it, what is one of the biggest issues we're faced with in this state? Closing the achievement gap," Tollison said. "There's a correlation between low achievement and student poverty. We're doubling the money; I don't know why anybody is opposed to that; that's what the irony is. The people you would think would favor that, I think, voted against this."

Several Democrats on the House side voted against this change because using Census data could mean using seriously under-reported numbers of students from low-income homes. Additionally, using census data would not discount all the students in the school district who attend private schools. This measure lowers some districts' poverty rates despite their high number of low-income students.

Reeves, too, emphasized how low-income students "lost" when senators voted down the measure last week.

"There are a lot of kids (that) come from backgrounds, and have (come) from lower-socioeconomic backgrounds that were going to be funded at a higher level than they are currently getting funded right here in the central Mississippi area," Reeves told reporters after the vote.

Reeves said Madison and Rankin Counties would see more funds under UPS. "Jackson Public Schools would have received millions of dollars in more money, had this bill passed," he added.

Republicans left the "27 Percent Rule," a current part of MAEP, in their new formula proposal. EdBuild Chief Executive Officer Rebecca Sibilia told lawmakers on both ends of the Capitol that the rule is one of the most inequitable parts of how schools are funded in the state. The 27 Percent Rule allows districts to only pay 27 percent of the total cost of funding their schools—even if they can afford to pay much more after they levy the minimum of 28 mills in local property taxes.

"As a result, the state is, in essence, providing a subsidy of almost $120 million to districts that could otherwise generate more funding from local sources to support their schools if expected to contribute at the same tax rate as the rest of the state," the EdBuild report, published a year ago, says.

The 27 Percent Rule provides a subsidy to 53 school districts statewide, but Pascagoula, Madison County and Lowndes County Schools make up nearly $40 million of the $120 million.

For larger districts, the rule has much less of an impact for total district funding. In Madison County, the 27 Percent Rule leaves $1,115 extra funding per pupil, EdBuild's report estimates, while in Jackson Public Schools, the rule means just $23 more per pupil. The rule does not help the majority of districts throughout the state at all. The authors of the EdBuild report insisted that eliminating the 27 Percent Rule was important to ensuring equity in the new formula, and House Democrats introduced several amendments to phase the rule out—all to no avail.

Speaker Gunn committed to looking at the rule during the proposed two-year phase-in period, but the actual legislation kept the 27 percent rule inside. Tollison admits that the rule is an issue—but addressing it he said is like doing a Rubik's Cube.

"We've got to stop it because it's going to continue to get worse as the Madisons and the Pascagoulas grow their tax base," Tollison said at the Capitol last week. "This is happening all over the country.... The wealthier communities are getting wealthier, and the rural areas are getting smaller, and you see that in the loss of student population, but their tax base is not growing as fast as Madison and Pascagoula."

Bryan, one of MAEP's authors, acknowledges that the 27 Percent Rule does need to be looked at and adjusted—but not in isolation.

"It's playing a much greater role today, and at least a part of that because of failure to fund the formula," Bryan said.

What's Ahead for Funding?

If lawmakers in the majority wanted to rewrite the funding formula, 2018 was likely the ideal year, because in 2019 all state legislators are up for re-election.

Tollison could not say whether the measure was dead until after 2019 or not. "I don't know the answer to that question; it will take some time to answer that," he told reporters last week.

Despite Bryan's successful charge to kill the proposal this year, he does not even sit on the Senate Education Committee. He said he would like to sit down and study exactly what is going on with special education and vocational-technical education funding currently under MAEP.

"The first step is to find out if anything is wrong. The proponents of this piece of legislation say 'you've got a problem,' but they never sit and try to figure out what it is," Bryan said.

Educators throughout the state want to see a more transparent process moving forward with more public meetings than EdBuild staff and Republican leaders held on the new funding formula proposal. EdBuild staff went to a handful of districts in 2016 and also met with several groups, including Mississippi Professional Educators.

"Let me stress, we appreciated being in those meetings, but there needed to be more of those meetings with more groups and town-hall meetings throughout the state," Riley told the Jackson Free Press. "The local citizens were not involved in this review as much as they were in MAEP."

Bryan estimates that lawmakers took about three years to get MAEP right before it passed by a bipartisan vote over Fordice's veto. Riley said many MPE members expressed concerns over how the legislation was rushed through the process.

"The fact that they are dropped at the last moment which minimizes the opportunity for vetting or analysis, they don't like that," Riley said. "As one member said, 'What are they trying to hide?' It just creates the appearance of impropriety."

The State will continue to use MAEP for now, and Reeves said school districts, especially ones that lose enrollment next year, will likely see less funding.

"Since the plan didn't pass, the likelihood they will see less money next year even than they are seeing this year, is pretty high," Reeves said. "Maybe when the superintendents see that is ultimately the case, they are probably not going to like the fact that they lobbied so hard against a bill that benefited them or their school districts."

The UPS formula would have frozen enrollment numbers for school districts losing students for two years. This would have kept those districts from losing funding, while allowing districts that added students to their rolls to receive more funds. Tollison said he was unsure if those additional funds will still go to MAEP.

"I think that will be decided in conference," Reeves said.

Lawmakers will vote on a budget bill for public schools this month, but a new formula plan will likely have to wait.

Email state reporter Arielle Dreher at [email protected]. Read more at jfp.ms/edbuild.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus