Mississippians turned out to support a protest at the University of Southern Mississippi in 2017 right after Donald Trump implemented a Muslim traval ban. Photo by Ashton Pittman.

JACKSON — When U.S. Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith took the microphone on a chilly Nov. 2 in Tupelo, Miss., she could not possibly have known what lay ahead for her campaign. Wearing a long coat, she stood in front of a statue of Elvis Presley when she told the crowd that if her friend Colin Hutchinson "invited me to a public hanging, I would be on the front row."

The two reporters in the audience—which included Wayne Hereford, an African American broadcast reporter for WTVA—did not seem to think a whole lot of the comment at the time.

Maybe it was a bit crude or "frontier bravado," Tupelo's Daily Journal reporter Caleb Bedillion would later write in a mea culpa column, but "reporting these remarks didn't occur to me."

"More bluntly put, however, I heard what I heard because I am white."

Once the video went viral on Sunday, Nov. 11, many black Mississippians and Americans, and their more attuned white allies, though, immediately heard what sounded like the biggest racist dog whistle since the Willie Horton ad days of the late Republican strategist and party chairman Lee Atwater. The South Carolinian loved to get fellow southerners to vote Republican by pandering to racist tendencies and pulling the bigotry out of latency if needed.

How dare this white woman talk glibly about a hanging in the state with the most lynchings? The state where black men hanging dead in trees were treated like a white-glove garden party with children milling about? The state where white people mailed postcards with photos of the horrific scenes to friends and family?

From 'Hanging' Quip to 'Segregation Academies'

Underlying race tensions catapulted to the surface of the run-off race between Hyde-Smith and former U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Mike Espy, with a series of other race-related reveals emerging about Hyde-Smith: a "joke" about voter suppression of liberal college students and photos of her wearing a Confederate cap at Jefferson Davis' last home, calling the Civil War "Mississippi history at its best!"

Then, this newspaper revealed four days before the run-off that Hyde-Smith had attended one of Mississippi's original segregation academies where she was surrounded regularly by Confederate icons. She then sent her daughter to one nearby that had one black student as recently as 2016.

Notably, these revelations indicating at least an embrace of a "lost cause" romanticism about the Old South also upended the usual Mississippi Republican playbook, or at least ripped it open for more to examine and vet what's inside. That meant an intense two weeks of a national and local public conversation about racism, "school choice," Confederate symbols and more—a much louder public dialogue on racism than most probably have witnessed.

Republicans, especially Hyde-Smith, who kept hiding from the press, seemed on their heels and worried about the impact on the run-off, bringing both President Donald Trump and Vice President Mike Pence for two rallies before the run-off in Biloxi and, yes, up in Tupelo where her "hanging" comment had thrown her campaign into defensive mayhem.

As for Democrats, African Americans and allies of other races, it was an enthusiasm rush. Many had visions of finally sending the first black U.S. senator from Mississippi back to Washington since the nation caved and gave the South its desired end to Reconstruction, setting up another century of oppressive Jim Crow laws, building on the South's existing black codes and "pig laws," that still haunt and hurt the South.

The question after the run-off ballots are counted—regardless of who won—is whether a nearly 50-year-old strategy to use bigotry to get Republican votes is finally entering its twilight stage. Will the suddenly honest dialogue about the tools, strategy and symbols of white supremacy be enough to force a new kind of politics?

The Ghost of Lee Atwater

It was a vicious, and misleading, 1988 television ad that ushered in today's toxic race politics. Lee Atwater, George H.W. Bush's campaign manager, decided to "go negative" on Democratic opponent and Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis, with an eye on winning more southern voters for Bush, who wasn't exactly a down-home southern type. He chose the case of William Horton, a convicted felon who went home on a Massachusetts furlough program—actually signed into law by a previous Republican governor—but didn't return on time, and committed rape and robbery.

A documentary on Atwater and his tactics, "Boogie Man: The Lee Atwater Story," shows an ad designed to make Horton look scary to white people, an approach Atwater later apologized for using when he was dying from a brain tumor at age 39. They even called him "Willie," which he never went by. But the strategy worked, helping hand Bush the victory, and is still considered by many the moment the "southern strategy" of appealing to racist beliefs for votes kicked into high gear.

"In 1988, fighting Dukakis, I said that I 'would strip the bark off the little bastard' and 'make Willie Horton his running mate,'" Atwater later said, quoted in his New York Times obituary.

"Republicans in the South could not win elections by talking about issues," Atwater said, per the Times. "You had to make the case that the other guy, the other candidate, is a bad guy."

By the time the "hanging" tape of Cindy Hyde-Smith went live on Nov. 2, a series of mailers for the state GOP's negative flyers falsely indicating that opponent Espy was a "corrupt" "criminal" were already distributed statewide. In the week before the Nov. 6 election, where the two candidates defeated the supposedly most racist candidate Chris McDaniel (according to state GOP leaders, including Gov. Phil Bryant and state chairman Lucien Smith), the Mississippi GOP sent glossy mailers daily depicting Espy as a corrupt criminal who doesn't pay taxes and can't be trusted.

It is easily recognizable as Atwater-esque dog-whistling to make white voters fear a black candidate, right down to darkening Espy's skin tone and showing him with jail bars. The mailers did not mention that he was exonerated on decades-old charges that even Justice Antonin Scalia said were bogus. The mailers left the impression that Espy is another black ex-con that Republicans want their constituents to fear, the same fears Atwater fanned when he conceived attack ads back in the 1980s.

It's a game a Mississippian—Haley Barbour—helped Atwater play to bring southern voters to vote for Republican Ronald Reagan, who campaigned for president at the Neshoba County Fair talking about state's rights, near where three civil rights workers killed by the Klan were buried under a dam in 1964. They then played it again to bring southern voters to the George H.W. Bush side. Whether it's communicated with Colonel Reb wedding cakes or references to whorehouses when talking about Head Start, which serves many black families, it's a game that has pushed conservatives gradually toward the Republican Party since the 1960s with the final transformation coming into full fruition after President Barack Obama's election, culminating in a supermajority in the Mississippi Legislature by 2016.

The strategy also laid the groundwork for the election of Donald Trump. By the time he kicked off his campaign saying Mexicans were racists and murders, America had adjusted to four decades of dog-whistle rhetoric passing for truth.

The current rules are simple: Stoke the embers of racism in every white person possible by associating the Democratic opponent with President Obama or Rep. Bennie Thompson from the Delta, or the Clintons, who have long been popular in much of the black community.

Atwater himself explained in a 1981 taped interview how racist political strategy had developed over time since Dixiecrats were yelling the n-word in the 1950s to the new Republican Party he helped re-create—which instead fixated on welfare cuts and entitlements by the 1980s to convey the wink-wink race-baiting message.

"You start out in 1954 by saying, 'Nigger, nigger, nigger.' By 1968 you can't say 'nigger'—that hurts you, backfires. So you say stuff like, uh, forced busing, states' rights, and all that stuff, and you're getting so abstract. Now, you're talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you're talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is, blacks get hurt worse than whites.... 'We want to cut this,' is much more abstract than even the busing thing, uh, and a hell of a lot more abstract than "Nigger, nigger." (Asterisks added)

Fast-forward to today's GOP mailers with lies of omission or half-truths at best accusing opponents of corruption or Jackson crime or African dictators or kids supposedly denied pre-existing conditions to tie those candidates to something that white people fear, often using fear to crime to get a pro-development candidate, for instance. It may be toxic and usually dishonest, but it's been a winner since Atwater perfected the science. The southern strategy hasn't been around since the 1960s for nothing.

Atwater himself, a boisterous figure who ironically loved to play and sing the blues, told himself that his strategy would help Republicans move past race. "My generation," he insisted in the 1981 interview, "will be the first generation of southerners that won't be prejudiced."

But the Republican Party in Mississippi has gotten whiter since the days when Atwater used to pop into the state for strategy visits and socializing. Jan Mattiace, a white Jackson businesswoman and long-time Republican, worked for the Mississippi Republican Party in the 1980s. She remembers Atwater's visits at a time when more black members were still actively involved in the party.

Now, Mattiace is backing away from the party because of the divisiveness of Donald Trump. (She voted for Libertarian Gary Johnson for president in 2016). She said before the run-off that she planned to vote for Mike Espy against Hyde-Smith and may well support a Democrat for governor next year. When he was in Congress, Mattiace said, Espy reached out to the Mississippi Republican Party. "He invited the entire delegation to come to his office," she said in an interview. "... I've always seen him as a leader."

With the polls not yet closed in the U.S. Senate run-off between Espy and Hyde-Smith as of this writing, it is impossible to know if the strategy worked again to help Hyde-Smith keep her appointed seat—or if a large enough coalition of African Americans, whites and others came together to upend it to elect Mississippi's first black senator since Sen. Blanche K. Bruce, who served from 1875 to 1881, during the end of the Reconstruction era. "He had good Virginia blood in his veins, and showed few of the marked characteristics of the negro race," the Times-Picayune in New Orleans condescended in Bruce's obituary.

Regardless of who won on election night, though, Mississippi feels different since Hyde-Smith's hanging comment and subsequent refusal to speak a sincere apology and use the incident to try to heal division. More people are facing the realities of such toxic politics, and lack of truly empathetic apologies, and the state GOP was on its heels in Mississippi for the first time for its race-soaked stunts since it started seizing power here in the 1970s, and ensuring that black and white voters stayed on two different tracks. Not to mention, Republicans had to spend massive money on the campaign, outspending the Espy campaign three-to-one.

From Dixiecrat to Republicans

Politicking has long been hot and heavy at the Neshoba County Fair in Philadelphia, Miss. In the 1960s, racist Democrat Ross Barnett would take to the stage under the pavilion to play his ukulele and call for resistance against all the "communist" and "liberal" and, of course, "outside agitators," as anyone fighting racism in the state has long been called. And he wasn't the only one. Still today, many conservatives use those labels for anyone standing up for better race relations and calling out racism.

But there was a gentleman's code about how to play politics within the state. That cracked apart when a young Republican, 34-year-old Haley Barbour, decided to run against long-time U.S. Sen. John C. Stennis. The senator from Dekalb, by then almost 81, was a segregationist for much of his more than six-decades-long political career, although he softened somewhat later. He was an old Democrat, after all.

Barbour was one of the early new Republicans who came of age during the civil-rights strife of the 1960s who wanted confused and left-behind segregationist Democrats to bring their votes to the GOP he and others were trying to give new life to. That ultimately successful goal meant that many poor and middle-class whites would end up voting on behalf of the large corporations Barbour would eventually lobby on behalf of in Washington, D.C., in addition to foreign countries.

So Barbour decided to run against Stennis to start the wave.

At the Neshoba County Fair that year, Barbour introduced the kinds of tricks against the elderly statesman that would hint at the un-gentlemanly southern political strategy that lay ahead.

He went after an old man's age.

The morning of what was then called "Jackson Day," young volunteers were out at the fair early to hang huge "Happy 81st Birthday" banners for Stennis near the pavilion. When it was close to time for Stennis to speak, they suddenly rolled out a cake with 81 lit candles as Students for Stennis volunteers surrounded to keep it from getting to the senator for the cameras. (The co-author of this story, Donna Ladd, was one of those volunteers surrounding the cake. She was also a John C. Stennis scholar at Mississippi State University.)

The point, of course, was to beat Stennis with trickery to show he was too old. Barbour failed, though, and Stennis was re-elected. He would die at age 93 still a Democrat, but one stuck in that era between the past of the two political parties and their rapidly changing futures.

Becoming the Party of Strom

Often when the subject of racism in the modern Republican Party comes up, party leaders and supporters will point to the Democratic Party's history of slavery, lynching, Jim Crow and the Ku Klux Klan. They will contrast it to the Republican Party, which was founded as a party devoted to the abolition of slavery, at least in principle, and certainly to stopping its spread to new states as the South insisted. They usually do not mention, or perhaps know, that the GOP of the 1800s staunchly believed in the principles of today's Democratic Party, and vice versa, well beyond race.

When Blanche K. Bruce served in the U.S. Senate during Reconstruction, nearly a century before the modern Dem-GOP party switch, he was part of the "black and tan party" due to black support until the racial upheaval of the 1960s. When blacks in the South first started joining the GOP after the Civil War, their faction was called the Negro Republican Party.

In those days, Republicans supported federal intervention—basically the exact opposite of what the GOP today has stood for since the 1960s.

"[L]eaving slavery and race entirely aside, the salient Republican policies of the mid-1860s (activist big' government, pro-income tax, pro-economic intervention) more or less match up to the Democratic policies of the early 2010s, while the Democratic policies of a century and a half ago (small 'limited' government, pro-localism, pro-states’ rights) bear a striking resemblance to contemporary Republican shibboleths," Hendrik Hertzberg wrote in The New Yorker in 2011.

That is, today's talking point that the modern Republican Party is the same one that freed slaves under Lincoln is patently and historically false—even aside from slavery and race issues.

Still, with rhetoric clearly designed to obfuscate its lack of African Americans devotees, today's Republicans point to the Grand Old Party's first president, Abraham Lincoln, who ended up issuing the Emancipation Proclamation to free slaves after a devastating Civil War. When Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens—a Democrat—announced the Confederate Constitution in 1861, on the other hand, he said its "foundation" and "cornerstone" rests "upon the great moral truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition."

Lincoln, however, has never been a particularly popular figure among many southern conservatives, whether when they were Democrats or now in their new Republican home. At the same Tupelo rally where Hyde-Smith made her infamous "public hanging" remark, she seemed unaware of the modern GOP's preference for reimagining today's southern white conservatives as having been Republicans all along—the heirs of Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, and absolutely not the ideological offspring of racist Dixiecrats who divorced the Democratic Party and took on a grand new name: Republican.

"You have people that say, 'She used to be a Democrat,'" Hyde-Smith told the crowd as she stood in front of a statue of Elvis that November morning. "Anybody in Mississippi 40 years old or older has voted for a Democrat. I've got news for you. Many years ago, everybody was."

Indeed, most white Mississippians did vote for Democrats 40 years ago because the realignment of the Democratic and Republican parties was not yet complete in Mississippi, especially in state and local races. That complete transformation would not occur fully in the South until Barack Obama was elected president in 2008, leading to many defeated Democrats and defections, such as Democrat Cindy Hyde-Smith, to the Republican Party by 2010.

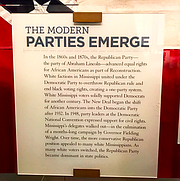

The Mississippi Museum of History has an exhibit explaining the party switch. "Over time, the more conservative Republican position appealed to many white Mississippians," the placard concludes after an explanation of the civil-rights disagreement that brought the change. "As many white voters switched, the Republican Party became dominant in state politics."

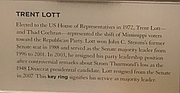

As an example of a politician who started out Democratic, then became Republican (while maintaining the same views), the museum points out former U.S. Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott—first a Democrat, later a Republican—who often interacted with white-supremacist groups and praised the n-word-using Sen. Strom Thurmond's infamous and racist run for president as a Dixiecrat sergregationist, . The statement ended Lott's political career; he is now a lobbyist.

"''I want to say this about my state: When Strom Thurmond ran for president, we voted for him," Lott said in remarks after Thurmond died. "We're proud of it. And if the rest of the country had followed our lead, we wouldn't have had all these problems over all these years, either.''

The party switch started as early as the 1940s, but got a jolt of energy in 1964. In July of that pivotal year, as white resistance to civil-rights efforts turned bloody in the south, Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act, after votes from both parties, but enraging white southerners who had identified as Democrats since slavery, secession and Reconstruction times.

Then, in August 1964, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, led by civil-rights activist and sharecropper Fannie Lou Hamer, demanded that their delegates be seated at the 1964 Democratic National Convention, rather than the "segregationist Democrats"—as Dixiecrats were also called—who dominated the official state party. That led to a walkout of the all-white Mississippi delegation, and the MFDP refused a party offer to compromise by giving them just two seats with no voting power.

Segregationist Mississippi politician Charles Pickering—later a prominent Republican judge whose name would surface in the Brett Kavanaugh Supreme Court hearings—attributed the actions of Hamer and her compatriots to his decision to leave the Democratic Party. Pickering said the people of Mississippi "were heaped with humiliation and embarrassment at the Democratic Convention."

Pickering left the Democratic Party a month later, encouraged by his law partner, Lt. Gov. Carroll Gartin, a fierce segregationist Democrat who fought against the Supreme Court's order for Mississippi to integrate its public schools until his dying day in 1966.

Gartin, whose name graces the Mississippi Supreme Court building in Jackson, built in 2011, also presided over the creation of the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission in 1956, which Pickering voted to fund. The state-funded agency spied for years on "communists" and "liberals" supporting civil rights for black people like the right to vote, or on a gas-station owner allowing a black man to use his bathroom in Philadelphia, Miss, less than a year before the Ku Klux Klan killed civil-rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner in the county.

'The Uptown Klan'

Carroll Gartin, law partner of Charles Pickering, was a member of the Citizens Council, known colloquially as the White Citizens Council and called the "uptown Klan" by newspaper editor Hodding Carter Jr. because it attracted so many upstanding businessmen, including in Jackson. The organization formed after the 1954 Brown v. Board decision as an overtly white-supremacist group that preached until it closed in 1989 that black people were genetically and biologically inferior, more prone to crime and were poor workers.

Citizens Council leaders certainly did not want white kids going to school with black ones because that would, in its words, disrupt white "racial integrity"—a white-supremacy phrase dating at least back to the eugenics efforts of the 1920s. The Citizens Council, led from Jackson by William J. Simmons with chapters around the country, even in San Francisco, would have many devastating impacts on the city and the state. One of those was plowing the ground for the later "southern strategy" by constantly publishing over-hyped accounts of black-on-white crime (from a state where white-on-black violence was rampant and seldom prosecuted).

The Lies Scientific Racists Told About Jackson’s Children

The Citizens Council, based in Jackson, published lies about the inferiority of African Americans for decades. It also ran whites-only academies.

But none were more devastating than the Citizens Council's efforts to get white families to flee the public schools once the group realized that federal enforcement of Brown v. Board of Education was inevitable.

After the Supreme Court definitively ordered immediate desegregation in 1969, the Citizens Council extended its influence by helping white families bypass integration by funding all-white "segregation academies" —the early "school vouchers"—and itself setting up multiple Council schools around Jackson. Many of those schools were quickly cobbled together once it became clear that white parents' only other option was to continue to send their children to public schools where they would soon be joined by an abundance of black classmates.

The schools taught the "scientific racism" of black inferiority and kept materials espousing the bunk science right in school libraries for students to study.

Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant attended Council No 2 McCluer, one of eight Citizens Council-run academies in Jackson receiving state tuition assistance. The original Council McCluer was on the site of what is now New Horizon Ministries, a complex of small businesses, a gym, after-school programs for children and more run by Ronnie Crudup Jr., an African American man working, in an ironic twist, to bring back the vigor of south Jackson since white flight devastated it in recent decades. Crudup had no idea that the property used to house a Council school until the Jackson Free Press told him. Council McCluer eventually morphed into what is now called Hillcrest Christian School, a private school now at a different location nearby.

In the 1970s, local newspapers treated announcements from those schools about sports and other honors the same as public schools, while running photos of children with a "Citizens Council: States Rights, Racial Integrity" placard in front of them. Bryant does not publicize that he attended Council McCluer School in south Jackson, but a local historian confirmed it by examining yearbooks for a column in the Jackson Free Press last year. Those photos show that the leaders of the Citizens Councils of America in Jackson, including Simmons and Medford Events, also were officers of the school.

"[A]dmitting blacks lowers educational standards," Simmons told The Clarion-Ledger in 1985. "Racial mixing is wrong when it's forced. And if it's not forced, it's not likely to occur."

Cindy Hyde-Smith also attended a segregation academy, as the Jackson Free Press reported on Nov. 23. Lawrence County Academy opened in 1970, just after the desegregation order. In one group photo in a 1975 yearbook, a young short-haired Cindy Hyde, in her sophomore year, poses with her fellow cheerleaders; at the center of the photo, the mascot, dressed in what appears to be a Confederate general's uniform, holds up a large Confederate flag.

Hyde-Smith cannot be held accountable for where her parents sent her, many pointed out after the story published. Still, as an adult, she sent her daughter, who graduated in 2017, to Brookhaven Academy, which opened as a segregation academy the same year as Lawrence County Academy, and received help early on from the Citizens Council. As recently as the 2015-2016 school year, Brookhaven Academy had only one black student, despite the fact that Brookhaven is majority black.

Perhaps most telling is Hyde-Smith's and the governor's reticence about talking about their education in their formative years, unlike many who openly discuss experiences in "seg" schools over the days since that story published.

Jan Mattiace, for instance, recently talked about her family sending her to the all-white Canton Academy as the answer to forced integration. She also grew up loving the Confederate flag—not knowing what it represented. As an Ole Miss student, she remembers stadiums full of people waving little rebel flags at games, but now rejects that teaching as an adult.

"I waved those flags," she said, adding that she hadn't been taught anything different. It wasn't until the university's first black cheerleader, John Hawkins, refused to carry a large rebel flag on the field in 1982 that Mattiace started understanding.

Now, Mattiace serves on the board of Dialogue Jackson, an organization that promotes deep conversations about race division and reconciliation.

For many in the Deep South, private schools born out of race hatred—as opposed to ones created out of religious faith or devotion to a complete education—and remain a fact of life. It's no secret that many white parents still send their children to them to avoid schools with significant numbers of black students, with many citing "safety" as a reason—not unlike white families around the nation who are sending their children to schools with little diversity. Others insist the segregation academies serve the purpose today of giving parents a higher quality educational option than some public schools allow.

The academies, much like the state flag, are the elephant in the room that many Mississippians would rather not prod.

People born and raised in Mississippi—like the authors of this story—know we are not supposed to talk about this recent race history and its effects on today. But, if not, little changes.

Besides, many Mississippians of all races are ready to talk about it now.

'We Have to Do This Continually'

In late 2015, the University of Southern Mississippi took down the state flag, which has the Confederate battle emblem in its canton, from one of the three flagpoles in front of campus where it once flew alongside the American flag. Every Sunday since, the Delta Flaggers—a group of dedicated supporters of the current state flag—have shown up to campus to fly, not one, but sometimes dozens of Mississippi state flags of various sizes.

Mississippi Flag: A Symbol of Hate or Reconciliation?

The Mississippi Sons of Confederate Veterans are fighting hard to keep the state flag to honor the Confederacy. Others are fighting back.

For nearly two years, the Flaggers met little resistance from students on campus or residents of Hattiesburg. That all changed, though, after neo-Nazis carrying the flag of the Third Reich marched alongside Confederate-flag-wielding white supremacists in Charlottesville, Va., with one murdering peaceful counter-protester Heather Heyer.

The next day, the Delta Flaggers showed up on campus carrying state flags and Trump flags. This time, though, they were met with resistance from dozens of students who spontaneously organized on social media to take a stand, as Heyer had done in Charlottesville.

The scene at the front of the campus was like a dysfunctional but authentic Mississippi family photo, complete with young Mississippians—white and black—holding up a Black Lives Matter banner and raising anti-racism placards in front of a massive state flag guarded by a group of mostly older, mostly white Mississippians, who on several occasions burst into singing choruses of "Dixie."

A week later, the students' protest grew to hundreds, and included professors and other town residents. For about two months, the Delta Flaggers, who had previously claimed the campus entrance unchallenged, met resistance from students and townspeople who were no longer content to see a symbol of slavery given free reign to fly on their campus.

"We come in masses, we come strong," Jojo Virgil, an African American student, told the crowd as they gathered around him at one of the dueling Sunday protests. "We pack a powerful punch. People don't see it, people don't know it. But when we come together, it can be felt, and it can be heard. So we have to do this continuously."

State flags flying on college campuses was "normal"—until enough Mississippians decided it was not. Academies that operate under the guise of offering a superior private school education while still functionally serving as segregation academies is "normal," but after this Senate election, Mississippians are questioning that, too. Even Hyde-Smith's "public hanging" remark was once a common southern phrase during the time when lynchings were also common, University of Alabama linguist Paul Reed told The New York Times.

Clearly, many now would rather never hear that phrase again.

What Next, Mississippi?

As a whirlwind of race-related debates draw to an end with this week's run-off election, what happens next? Certainly, parts of the mis-education of many Mississippians—and Americans—about seldom-discussed realities like "seg academies" was erased in recent days and weeks.

EDITOR'S NOTE: GOP Leaders, Stop Disrespecting Black Mississippians

Editor Donna Ladd's letter to GOP leaders about decades of political racism.

The country learned that "school choice" and vouchers started out as ways to incentivize white families for pulling their children out of public schools in the South and enrolling them in all-white schools. The dialogue nationally also moved organically to the question of the problem of de facto segregation schools, public and private, far from Mississippi that offer better education and service to affluent white children.

Here in Mississippi, our history of toxic race policies were laid bare, from the "criminal" mailers about Mike Espy to open talk about schools built to shield white children from societal diversity. It's easy to wonder if, as with many state elections, this fervor dies down as we have a winner and move into the holidays and toward state elections.

The difference this time seems palpable, at least as we approach the closing of the polls. The number of Mississippians who voted swelled for the Senate election, including many African Americans and young people of various races. Volunteerism spiked, and get-out-the-vote efforts, such as by Mississippi Votes and Black Voters Matter was intense. It's hard to imagine these zealous efforts, or the conversations provoked by revelations during the election cycle, just dying out now.

Rukia Lumumba is an attorney and founder of the People's Advocacy Institute, an organization that leads grassroots voter awareness and registration drives; she is also Mayor Chokwe A. Lumumba's sister. She spent weeks working with other organizers to turn out the vote on Election Day and then to the run-off.

Lumumba takes the long view, believing the fervor will continue. "It's time that we take back our democracy, and Tuesday is just the start; it is not the end," Lumumba told Jackson Free Press reporter Ko Bragg just before the run-off.

"It's a continuation of a struggle we've always been waging in Mississippi because what happens in Mississippi really does matter to the world."

Note: U.S. Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith won the run-off to serve the remainder of former Sen. Thad Cochran's term, but Mike Espy came closer than any Democrat in decades. Three days later, on his 65th birthday, Espy announced that he is running again in the 2020 election That decision is likely to keep enthusiasm high among Democrats and critics of Hyde-Smith for the next two years.

Comment: jacksonfreepress.com. Follow writers on Twitter at @ashtonpittman and @donnerkay.

More like this story

- EDITOR'S NOTE: GOP Leaders, Stop Disrespecting Black Mississippians

- Mike Espy Came Closer to Senate Seat Than Any Dem Since 1982

- Republicans Call Espy ‘Sexist’ for Saying He’s Better for Women

- Full ‘Public Hanging’ Video Surfaces, Revealing More About Hyde-Smith’s Views

- Mike Espy Vows to 'Correct Our Mistakes' in New U.S. Senate Campaign