The sign near the University of Mississippi notes the place where murderers dumped the ravaged body of 14-year-old Emmett Till in the Tallahatchie River in 1955—apt punishment, his murderers thought, for whistling at a white woman. Photo courtesy Simeon Wright

I miss Will Campbell every day. Boot-leg preacher, civil rights activist, prophet to the South, Will was also my mentor. I miss him the most when his beloved state of Mississippi is forced to reckon with the legacies of its racial past.

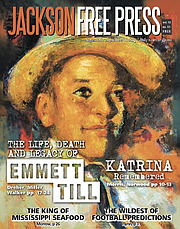

You have likely heard of the University of Mississippi students who thought it appropriate to pose with guns one night for a picture in front of a bullet-strewn purple marker. The sign notes the place where murderers dumped the ravaged body of 14-year-old Emmett Till in the Tallahatchie River in 1955—apt punishment, his murderers thought, for whistling at a white woman. The Emmett Till Memorial Commission, a biracial group established in 2005 and made up of local citizens in Tallahatchie County, have seen it as a labor of love and a mission of restorative justice to honor Till's memory and tell the story so that such atrocities might be prevented.

The mockery of that memory incites anger; it cannot easily be dismissed as "boys will be boys" or the harmless mischief of youth. The sign is isolated, down a gravel road 10 minutes outside of town. You have to know it's there; you have to be looking for it. The intentionality of this act shocks the senses. It is understandable, as many on social media have asserted, to want to dismiss the perpetrators from society, to lock them up and throw away the key.

I worked at the University of Mississippi for 20 years (and received a graduate degree there before that). For most of that time, my job was to address racism. Modeled on the work of Ella Baker and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, I grew the William Winter Institute from an idea to an organization that supported grassroots communities across the state who were grappling with the racist histories of their communities.

Even though we were based at "Ole Miss," often the hardest work I did was at the university. Time and again I was directed not to engage in issues of justice in communities. When white supremacist speakers came to campus to exploit the image of "Ole Miss," I had to violate direct orders so that I could support students who wanted to counter-protest. These messages were overt and clear, albeit behind closed doors. Over time and especially under more courageous leadership, it became easier to be on campus, and so many talented faculty, staff and students worked hard to put into place curriculum, programs, and policies to both prevent racial incidents and to better respond to them.

And still, the campus itself is dotted with Confederate imagery that communicates exclusion to anyone descended from enslaved persons or to those who reject the Confederacy's white supremacist cause. How money is spent reflects long-standing prioritization of athletics over academics and especially a lack of support for efforts promoting diversity and inclusion. While we were given a free space, the Winter Institute never received any funding from UM or from the state; we raised all of our own support. And now that Institute is gone from campus. And recent university leadership seems intent on undoing all the work so many of us have done to move the institution forward, to make it more welcoming for all.

'The Segregationist ... Too Is a Child of God'

Now, here we are again, with the university approaching a new school year under the cloud of a hateful act and, through a tepid and incompetent response to that act, perhaps unsure of how to proceed. Amidst the backdrop of a racist occupant in the White House, stoking forces bent on maintaining a dominant white race, in the face of demographics and political movements that portend a multicultural future, we are in challenging times. What must be done?

In times past, I would call Will, and we would lament together. Often, our conversations involved Will talking me through my anger and directing that energy to a more productive next step. Since he's been gone, I've turned frequently to his books as a touchstone for difficult days. Right now, his small tome "Race and the Renewal of the Church" speaks to me. Written in 1962, Will questions whether the Christian church may even lay claim to the designation "church" so woeful has its record been on race up to that point.

But Will proposes a role that the church might play that I submit is a useful one for an educational institution to consider as well. He says, "the church must be concerned with the segregationist ... because he too is a child of God." But Will is clear that while the "church must understand" the racist, "at the same time it must not permit understanding him to mean that its own policy becomes silence or inaction."

Let us be clear that there are a variety of roles to be played, both by individuals and by organizations and institutions. My friend and social psychologist Layli Maparyan describes a "politics of invitation" and a "politics of opposition." Much like a church, a university should be welcoming to all and should uphold values of acceptance, diversity, belonging, inclusion and equity. It should work with students where they are, but never relent from teaching and upholding its values, the most important of which should be accountability and truth-telling.

Good teaching prepares faculty to invite students from all points of view into a learning environment that challenges learning edges while respecting the dignity of all students. At its core, a university invites all in, while maintaining its sense of itself as a place of learning and freedom.

'We're All Bastards, But God Loves Us Anyway'

For others of us, we may choose to use our gifts also to invite those into courageous and difficult conversations about racism and institutional inequities. Over 25 years into this work, I have seen remarkable transformations occur through this kind of community-building process. But there must also be the "politics of opposition," in which principled and ideally nonviolent individuals and groups use all direct-action tactics and indirect strategies to lift up the voices of all who are targeted and oppressed by inequitable systems and challenge the systems that continue to cause suffering and harm.

Each of us must decide what role is best suited for our gifts and what circumstances require. And organizations and institutions should, likewise, have clarity about their roles and then act accordingly. There will not be one solution, so we must be open-minded and creative. What is not permissible, at this precarious moment in the life of our nation, is for any of us to do nothing. Seek out relief in communities when you despair, but return as soon as you can because the work ahead needs all of us.

Congressman John Lewis said we must "create a culture where reconciliation is possible." In the parlance of our time, I submit this involves "canceling" behaviors that are dangerous and problematic but not canceling people. Through retributive justice where appropriate, and with transformative, restorative justice where able, the liberation of all people, both in body and spirit, must be our goal.

Will Campbell taught me that "we're all bastards but God loves us anyway." Even those young men in the picture. Even you. Even me. Let's all get free.

Susan M. Glisson is a co-founder and partner in Sustainable Equity (www.sustainableequity.net). She was the founding executive director of the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.