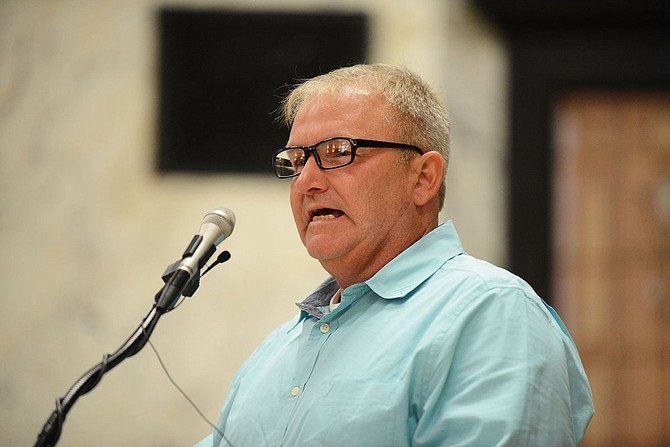

Wayne Kuhn still cannot vote—even though his record was expunged in December 2017. “I no longer have a criminal record here in the state of Mississippi but I still cannot vote,” Kuhn says. Photo courtesy Southern Poverty Law Center

NEW ORLEANS (AP) — A federal appeals court hears arguments Tuesday on the constitutionality of Mississippi laws that permanently bar certain felons from voting unless they can get their rights restored through what advocates say is a difficult process.

Six convicted felons are pushing to have their voting rights restored through a lawsuit filed in federal court in Mississippi. They have argued that the restrictions imposed in 1890 were designed to “permanently disenfranchise black voters.”

After a district court judge in August ruled mostly — but not entirely — in the state’s favor, the six felons and the state both appealed to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans.

The Mississippi Constitution strips people convicted of 10 specific felonies of the right to vote. Those crimes include murder, forgery and bigamy. The list was later expanded by the state’s attorney general to 22 crimes, including timber larceny and carjacking.

Those convicted of a crime can get their voting rights restored only by going through a process of getting individual bills passed just for them with two-thirds approval by the Legislature, or by getting a pardon from the governor.

The felons argued to the appeals court in briefs that those two laws: “...ensure that, with extremely limited and arbitrary exceptions, a citizen convicted in a Mississippi state court of a disenfranchising felony will never again vote in the state, no matter how minor the underlying crime or how long the citizen may live after sentence completion.”

The plaintiffs argue the lifetime voting ban is cruel and unusual punishment — a violation of the 8th Amendment. They also argue that the restoration process violates the constitution’s Equal Protection Clause because when it was adopted in 1890 it was intended to keep African Americans from voting and still disproportionately affects black people.

In his August decision, U.S. District Judge Daniel P. Jordan III threw out most of the challenges but left alive one challenge to how Mississippi allows people to regain their voting rights. Jordan previously certified the case as a class action, meaning it could potentially affect thousands of people.

The state argues that the secretary of state’s office, which oversees elections, doesn’t play a role in restoring voting rights and was wrongly sued. The state has also argued that the plaintiffs cannot prove any “present-day discriminatory effects.”

“There is no question that the U.S. Constitution expressly approves of the right of a State to disenfranchise felons — including permanently,” the state argued.D

Various groups have come together to support reinstating voting rights to felons — the libertarian Cato Institute, the American Probation and Parole Association, and the ACLU and Mississippi branch of the NAACP.

In its brief, the APPA argued that voting helps ex-offenders reintegrate into society.

“Denying released offenders this basic right takes away their full dignity as citizens, separates them from the rest of their community, and reduces them to second-class citizens,” the group wrote.

In its brief, the Cato Institute argued that Mississippi’s disenfranchisement law went far beyond what the Constitution intended when it allowed states to restrict voting rights and decried what it calls an arbitrary way of choosing which crimes could result in disenfranchisement.

“For every crime on the list there is a similar or even worse crime not on the list. Check fraud means permanent disenfranchisement. But credit card fraud carries no similar penalty,” the group argued. “By disenfranchising individuals for minor crimes, Mississippi drastically departs from the States that understand permanent disenfranchisement for what it is — among the most severe penalties our society can inflict.”

Copyright Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.

More like this story

- Mississippi Voting Rights Case is Argued at U.S. Appeals Court

- Federal Appeals Court to Review Jim Crow Felony Voting Ban

- U.S. Appeals Court to Hear Mississippi Voting Rights Case

- Mississippians Sue to Get Voting Rights Restored After Serving Time

- OPINION: Bring Mississippi Into the 21st Century—Overturn Its Jim Crow-era Voting Laws

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.