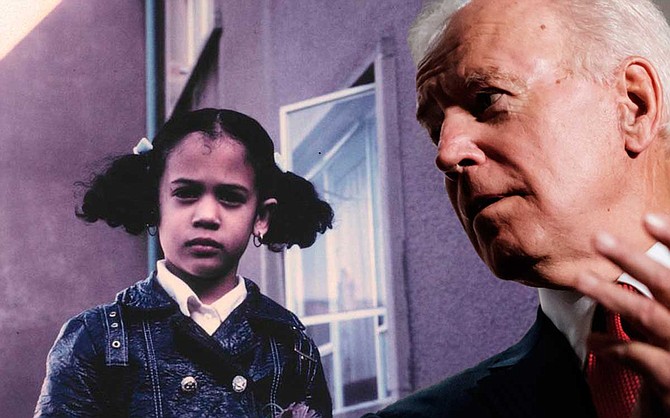

At a Democratic presidential debate on Thursday night, former Vice President Joe Biden defended himself after U.S. Sen. Kamala Harris of California criticized his opposition to busing—a program that guaranteed her a racially integrated education in the 1970s. Biden photo by Ashton Pittman; Kamala Harris photo courtesy of Kamala Harris for the People.

Even as the sun glistened upon his thinning hair one bright Mississippi day in DeKalb, Miss., U.S. Sen. Joe Biden stood out as the youngest of the senators speaking at U.S. Sen. John C. Stennis' birthday party. It was Aug. 3, 1985, and the 42-year-old Biden was a rising star in the Democratic Party. With the 1988 presidential race coming up, some hoped that he might help lead it out of the wilderness of the Reagan years.

Despite Biden's reputation as a northeast liberal, the young Delawarean wowed the southern crowd as he drew from the Confederate mythos to pile praise upon Stennis, who was known for his decades of resistance to civil rights. Biden compared him to Stonewall Jackson, a fabled Confederate military commander known for his tactical prowess.

"It was said of Stonewall Jackson, 'He is an avalanche from an unexpected quarter, a thunderbolt from a clear sky, and yet his character will make him a stone wall more than any man I've ever known,'" Biden said, reciting a quote that a 1920 book attributes to lecturer, and Stonewall Jackson's aide, James Power Smith.

"And Mr. Chairman," Biden continued, "When you stand on the floor of the Senate, and you point your finger, and you raise your voice, it's like a bolt from a clear sky. And when you speak, everyone listens. And as all of my colleagues have said here today, he truly does stand like a stonewall; he is the rockbed of integrity of the United States Congress."

Even in the company of other segregationists like South Carolina Sen. Strom Thurmond and Arizona Sen. Barry Goldwater, Biden did not mention Stennis' storied opposition to civil rights.

Biden on Busing: 'A Liberal Trainwreck'

A decade earlier, though, Biden worked with Stennis and other segregationists like Thurmond and Sen. Jim Eastland, Mississippi's other U.S. senator, to fight a key segregation program: busing, which the government used to send children across district lines to make schools more integrated.

Southern Dixiecrats and Republicans had long opposed busing in their region, where the federal government had mandated it most heavily. But as the practice spread, whites in wealthy suburbs like those in Delaware began pushing back. Some had moved to the suburbs to send their kids to what they considered a "good school," which usually meant mostly white, and opposed their kids being bused elsewhere to make schools more equal.

"Southern politicians who had been pushing against desegregation in the 1950s realized, 'Oh, OK, now that it's hit the doorstep of the northeasterners; they don't like it any more than we do,'" Ralph W. Eubanks, a southern studies professor at the University of Mississippi, told the Jackson Free Press in April. "And these political alliances began to form. So that's why you had someone like Joe Biden making alliances with Strom Thurmond, James Eastland and John Stennis."

In 1973, Biden ran on a pro-civil-rights platform. Just a year earlier, though, segregationist Alabama Gov. George Wallace had won the Florida Democratic presidential primary while running on an anti-busing platform. As the concern among white parents about busing grew beyond the Deep South, even some northeast liberal Democrats like Biden began criticizing it.

By 1975, Biden thought of busing as a "liberal train wreck," as he wrote in his 2007 memoir, and found himself huddled with a group of Dixiecrats, planning how they might introduce anti-busing legislation that could pass in the Senate.

"The new integration plans being offered are really just quota systems to assure a certain number of blacks, Chicanos, or whatever in each school," Biden told a Delaware newspaper in 1975. "That, to me, is the most racist concept you can come up with. Who the hell do we think we are, that the only way a black man or woman can learn is if they rub shoulders with my white child?"

Around that same time, all the way across the country in Berkley, Calif., a schoolgirl and future U.S. senator named Kamala Harris was reaping busing's benefits. With an African American father and a mother from India, Harris was the first in her family to go to an integrated school district.

'That Little Girl Was Me'

All these years later, on a Democratic presidential debate stage on Thursday night, Harris took aim at Biden, not only for his recent praise for the "civility" that segregationists like Eastland and former U.S. Sen. Herman Talmadge of Georgia showed him, but for his efforts to kill the program that integrated her school.

"Vice President Biden, I do not believe you are a racist, and I agree with you, when you commit yourself to the importance of finding common ground," Harris said. "But I also believe—and it's personal—it was actually hurtful to hear you talk about the reputations of two United States senators who built their reputations and career on the segregation of race in this country."

It was not only his praise of segregationists that bothered her, though, Harris said, but his efforts to end the very program that ensured her an integrated school experience.

"There was a little girl in California who was bused to school. That little girl was me," she said.

Biden deflected the criticism, claiming that his opposition to busing was about federally mandated busing. That decision, he said, should have been left up to states and local governments as it was in Berkley—not enforced by the federal government.

"The fact is that, in terms of busing, the busing, I never—you would have been able to go to school the same exact way because it was a local decision made by your city council," Biden said. "That's fine. That's one of the things I argued for. We should be breaking down these lines."

That "local control" argument both invoke the segregationists' "state's rights" argument—the racist Citizens' Council's logo was designed around the words "Racial Integrity" and "State's Rights"—even as it recalls Eastland's opposition to "forced busing ordered by federal courts," and Stennis' suggestion, in a 1973 letter to a constituent, that busing only existed to satisfy technocrats in the nation's capital.

"I am opposed to the busing of schoolchildren for the sole purpose of overcoming racial imbalance," Stennis wrote in that letter. "This unreasonable busing is injurious to our school children and only benefits some Washington socio-political statistician."

Stennis' opposition to busing was indicative of the mood in Deep South states, which showed no desire to implement busing on their own terms—a point Harris made Thursday night.

"There are moments in history where states fail to support the civil rights of people," she said.

In April, the Jackson Free Press spoke to Millsaps College civil rights historian Stephanie Rolph, the author of the 2018 book, ""Resisting Equality: The Citizens' Council, 1954-1989." Even today, she said, Biden would likely face pushback from some white voters if he apologized for his position on busing.

"It would be excellent if Biden could recognize the political moment he was in at that time and why he realizes that was an erroneous position. But that sort of contextual explanation for that for someone like him at the national level also threatens to undermine certain constituencies that would not appreciate his apology for that, because they might not think that anti-busing legislation was a bad thing," she said.

Thursday night was not the first time Harris has pointed to America's history of segregated public schools. In a speech in New Orleans last year, Harris praised the city for the election of its first African American woman mayor as evidence that America is better than the troubles of the Trump era.

"I know we are better than this because, less than 60 years ago, about four miles up the road, Ruby Bridges needed federal marshals to escort her to school," Harris said last August, referring to the civil-rights activist who, as a 6-year-old child, faced abuse and harassment when she became one of the first African American children to attend an integrated school in New Orleans.

"And yet today, Mayor Latoya Cantrell is the first woman—and first black woman—in history to lead this city. That's our American identity."

'A Man Without Guilt'

On Thursday night, Biden denied Harris' charge that he had praised segregationists.

"It's a mischaracterization of my position across the board. I did not praise racists. That is not true," Biden said on the debate stage.

Over the years, though, Biden has repeatedly praised segregationists like Stennis, Eastland and Thurmond.

At the 1985 birthday party in DeKalb, Miss., Biden effusively praised Stennis without reservation.

"He's an opponent without hate, a friend without treachery, a statesman without pretense, a victim without any murmuring, a public official without vice, a private citizen without wrong, a neighbor, as you all know, without hypocrisy, a man without guilt," Biden said. "A senator whom future senators can study with profit for as long as there is an America."

Just two years earlier in 1983, Stennis had voted against making Martin Luther King Jr. Day a national holiday—the only southern Democrat to do so. Just three other Democrats, along with 18 conservative Republicans, had also voted against the holiday.

Driving Mr. Biden: The JFP Interview

JFP Editor Donna Ladd toured then-Sen. Biden around Jackson in 2006 for an in-depth interview.

In 1982, though, Stennis voted to extend the Voting Rights Act, which he had fiercely opposed in the 1960s.

In a 2006 interview with Jackson Free Press editor Donna Ladd in Jackson during an earlier presidential bid, Biden recalled meeting with Stennis on the day of his retirement. Stennis, Biden said, told him that even though he had opposed it, the Civil Rights Movement "freed my soul."

Still, Stennis publicly admitted no remorse even as he was retiring, The Atlanta-Journal Constitution reported after interviewing him in 1988.

"Stennis offers no apologies for once fighting the lost racial causes of his beloved Mississippi. ... And as that career comes to a close, the 87-year-old patriarch of the Senate feels no need to offer excuses for having 'done my duty,'" the report reads.

Though Biden's speech, the full transcript of which Scribd user Andy William uploaded to the site on May 22, drew little notice in the mid-1980s, not all U.S. senators have been so lucky after praising segregationists at their birthday parties.

U.S. Sen. Trent Lott, a Republican who took over Stennis' seat after he retired in 1989, saw his career upended in 2002 because of comments he made at segregationist Thurmond's 100th birthday party.

"When Strom Thurmond ran for president, we voted for him," Lott said. "We're proud of it. And if the rest of the country had followed our lead, we wouldn't have had all these problems over the years, either."

Thurmond ran for president in 1948 as the nominee for the State's Rights Democratic Party, but won in just four states: Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi and his own state of South Carolina. Though he first served in the U.S. Senate as a Democrat, he switched to the Republican Party after Democratic President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act in 1964.

Lott's remarks at Thurmond's party drew such a backlash that Lott, who was the U.S. Senate Majority whip at the time, stepped down from his leadership position.

At Stennis' birthday party in 1985, though, Biden opened with a joke about Thurmond, then the chairman of the Senate Judiciary under whom he served. Thurmond, he joked, might announce a second run for the presidency.

"It's nice to be here, Mr. Chairman, on the day that Strom Thurmond announces for president of the United States of America ... I'm not sure, I think maybe Strom had the right idea, of leaving the party when he did, because now, you know, he's chairman of the judiciary committee, and I serve at Strom Thurmond's bidding," Biden said.

Biden also told the crowd that Stennis befriended him shortly after he joined the Senate.

"John Stennis, who knew little of this northern boy who was supposedly a liberal, who in fact he had never heard of, John Stennis befriended me," he said.

'He Won Their Hearts'

A year after the Mississippi birthday party, Biden visited Mississippi's sister state, Alabama. There, Howell Heflin, an Alabama Democratic state senator who had been at Stennis' birthday celebration, introduced Biden to a Democratic crowd, telling them how he had "enthralled" the Mississippians.

"He won their hearts and proved he ... understands the South," Heflin said.

Reporting on that trip on March 2, 1986, The Morning News in Wilmington, Del., reported that Biden "offered the crowd a bit of absolution, telling them that they had confronted their racial problems and dealt with them and, while everything was perhaps not perfect, apologies were no longer needed."

"A black man has a better chance in Birmingham than in Philadelphia or New York," Biden said.

Biden adjusted his regular stump speech for the Alabama crowd. The Morning News reported that he dropped a reference to his youthful participation in civil-rights demonstrations in Delaware and removed a reference to Birmingham Police Commissioner T. Eugene "Bull" Connor, who had set loose police dogs on civil-rights demonstrators in the 1960s.

Biden continued to insist that the segregationists he worked with on busing in the 1970s had truly had a change of heart. When Thurmond died in 2003, Biden spoke at his funeral.

"I believe that change came to him easily," Biden told the mourners. "I believe he welcomed it, because I watched others of his era fight that change and never ultimately change. It would be humbling to think that I was among those who had some influence on his decision, but I know better."

Joe Biden and the Dixiecrats Who Helped His Career

During his early years as a U.S. senator, Joe Biden counted Mississippi segregationist Sens. Jim Eastland and John Stennis as his mentors.

In April, Eubanks told the Jackson Free Press that he does not think "any of them really changed." Rather, he said, they responded to the changing political climate in the 1970s and '80s.

"I think they were not as outwardly racist and I think it became less acceptable for them to be so openly and blatantly racist," he said. "I think their racism was sublimated. It was not expressed outwardly. I can't really see into their hearts to know if they really changed or not. Yes, they voted to renew the Voting Rights Act. But at that point, they really didn't have any choice. That's not evidence of real change and atonement. It's more, 'We know the politics have changed, so we're going to go along with it.' And that's different. I think Biden read that as that they had changed, rather than confronting actual evidence that they had."

Six months after Thurmond's death, 78-year-old Essie Mae Washington-Williams publicly disclosed that she was Thurmond's daughter, born out of wedlock to a black mother. Though Thurmond had supported her and paid for her college education at a historically black college, the old-fashioned segregationist had kept his daughter's identity hidden while he was alive out of fear that it would harm his reputation if the public knew he secretly had a black daughter.

Years later, South Carolina added her name to a list of his children on his memorial at the state capitol.

Biden's campaign has not responded to multiple requests for comment from the Jackson Free Press since April.

Follow State Reporter Ashton Pittman on Twitter @ashtonpittman. Send tips to [email protected].

More stories by this author

- Governor Attempts to Ban Mississippi Abortions, Citing Need to Preserve PPE

- Rep. Palazzo: Rural Hospitals ‘On Brink’ of ‘Collapse,’ Need Relief Amid Pandemic

- Two Mississippi Congressmen Skip Vote on COVID-19 Emergency Response Bill

- 'Do Not Go to Church': Three Forrest County Coronavirus Cases Bring Warnings

- 'An Abortion Desert': Mississippi Women May Feel Effect of Louisiana Case

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus