State Health Officer Dr. Thomas Dobbs spoke with the Jackson Free Press in a phone interview on April 22, discussing at length the racial health disparities the COVID-19 crisis exposes. He described the steps the Mississippi State Department of Health is taking to address them in the future. Photo courtesy State of Mississippi.

Mississippi State Health Officer Dr. Thomas Dobbs is leading the public-health response to the COVID-19 crisis, directing the State Department of Health and serving as Gov. Tate Reeves’ chief health adviser on the virus and the state’s attempts to stem its spread.

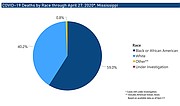

But the burden of COVID-19 is not equally shared among all Mississippians. Black Mississippians are acquiring the virus at a disproportionate rate, and their health outcomes paint an even harsher picture of health inequity. The day of this interview, MSDH announced a new total of 4,894 cases of COVID-19 across Mississippi, with 2,582 of those cases coming from the state’s black population. Of the state’s 193 deaths, there were 120 black fatalities.

Earlier this week, MSDH reached out to the Jackson Free Press to schedule an interview on the subject of black health disparities in the coronavirus crisis, and MSDH’s plans to address these burdens moving forward. This morning’s interview has been lightly edited for clarity. A portion of cross-talk regarding available data on deaths according to gender was excised.

NJ: MSDH has steadily provided more data portraying the racial health disparities of COVID-19. What does Mississippi's racial disparity in COVID-19 look like, and how do we compare it to other states in this regard?

TD: Well, clearly we have a disparity in deaths and in cases. If you look at our info, the latest information, you know, based on available data, 51.3% at least of our cases are African American. You know black folks only make up about 37% of the population. So there's a lot more—but then you can look at the deaths.

It's about 64% of the deaths. So that's really, really just unacceptably high. As far as how we compare to other parts of the country as a proportion, we're pretty much in line, unfortunately, with other states around the country. This is obviously not just a Mississippi issue, but because we have the largest percent population of African Americans in the (country), obviously the disparity is going to be a lot more obvious.

NJ: Underlying health conditions such as heart disease, lung disease and diabetes exacerbate the threat of this virus. Based on what I'm reading, it seems that virtually all of Mississippi's deaths have been from these at-risk populations. How much do those comorbidities explain the discrepancy in outcomes, but also the reports of infections in general?

TD: Yeah. So you know, clearly we do have health disparities underlying chronic illnesses. That is a part of the problem. We're trying to be careful not to state that that's the only issue, because we want to make sure that that black population is getting tested adequately. That's a possibility, also—access to care issues.

Are there other factors that play into the disproportionate number of infections and the disproportionate number of deaths? So, you know, that's going to take more investigation. Clearly the chronic disease burden is part of the equation, but we need to make sure that we investigate into other etiologies, other causes.

Because, you know, certainly if it's a testing access issue, that’s something that we can fix in the short term versus these, you know, decades and decades of health disparities and social inequality. That's not something that we're going to be able to resolve within a couple of weeks.

NJ: So, you raise a good point there where it comes to racial disparities and health-care access, clinic access. Does it follow that these disparities extend to COVID-19 testing? What I'm asking is, what metrics or numbers will give us confidence that there's not a racial testing gap hiding an even wider racial health impact?

TD: We have identified a way to … that data point is not something that's readily available, but we've identified a way that we could survey the negative case reports so that we'd get a proportionality of testing based on race and ethnicity. So that's something that we're working on and hope to be able to report out soon.

The other thing is we're doing a statewide survey of people, with a focus on African Americans, (to) understand what are the concepts within the black community, especially around COVID, attitudes toward social distancing, you know, attitudes towards risk, to make sure that we really understand, perhaps, where our weaknesses are in messaging or in access to care to the black community.

NJ: Is there anything that you've found that you can share with us so far? Weaknesses that are trying to be addressed right now? What's the progress?

TD: We’re still collecting surveys. But, you know, I'm hoping to have some preliminary data at least by the first part of next week. But we have thousands of them, and would like to get more if possible. And that’s a project we're doing in collaboration with Jackson State. So we want to credit their work.

NJ: So speaking of that, what is MSDH’s plan for viral surveillance and prevention, specifically in minority communities. Then following that, as we start to see a decline, what's the plan for preventing a resurgence in those exact same communities?

TD: Well, you know, certainly we're trying to target our resources into the most affected communities. And so it obviously makes sense that we're going to spend a lot of our testing and investigation efforts within the black community.

Even from the beginning—although maybe not intentional, but because we recognize these are communities that are affected—we started doing targeted testing in the Delta, in locations (like) Lauderdale County, in places where the black community is really badly affected.

So increasing access to testing is going to be very, very important. Additionally, we're trying to deploy rapid testing capabilities to areas where we know there is this health disparity, so that we can get more time-sensitive results, so that we can act more quickly.

So, resource deployment is going to be huge. And then, as we go forward, we want to move to a model that basically allows for testing, not necessarily that requires people to go somewhere. But if we find the case in the community where we've had an outbreak, we bring the testing to those homes, we bring the testing to those individuals where they live, so that any travel cost barriers are not part of the equation.

But we also have to be sensitive of a stigmatization or other distrust in every community, whether, you know, it's a black community, Hispanic, Vietnamese, and so that's something we'll have to be sensitive to.

NJ: That’s something that I was wondering about. With a lot of the mobile testing sites, I know you stress the need to use the C Spire health app that y'all are using. I'm wondering if, as there's targeting of some of these communities that have less access to health-care, less access to wealth, if there's a different system that can be used to set up testing, to set up registration.

TD: Yeah, exactly. We're going to have to change the paradigm to some degree. I mean, it has been useful and helpful. There is a phone line, though, people can access, just to make sure. You don’t have to have an app. You can just call in to get pre-screened.

But we do have the network across the state of well more than a hundred clinics that are testing. A lot of those are community health centers, and some of them have been doing fantastic work. I'd like to give a shout-out to Mound Bayou and the testing they've done, which has been phenomenal in the communities. Just doing low-barrier, high through-put testing, more of those sorts of things.

Different health systems have been really aggressive trying to make sure that they reach all communities. Hattiesburg has been great. Gulfport and Ocean Springs health systems have been really good. So, you know, there's a lot of opportunities for partnership to get folks out there, but we do need to bring it with low barriers where people can have easy access—and no cost—that's also going to be the key for folks who otherwise may not have good access to health care.

NJ: Pulling back and looking at the broader picture, black health disparity is not new in Mississippi—nor are the underlying conditions that so exacerbate the problem. Is there a plan to address the burden of disease on communities of color, moving into the future?

TD: Certainly. That's a tough one. And it's a multi-agency sort of thing. It’s an all-of-state responsibility to try to work on this, and it's going to take partners in the faith community and the academic community, and the government—political leaders. We have a huge role in that—The Department of Health, although we don't control all the leaders.

We have reformulated and reinvested in our health-equity division, with a specific focus on health disparities in the black community, but also looking at health disparities in LGBTQ folks, in people who live with HIV, making sure we look at Hispanic populations and that they have access to health opportunities.

And so there's a lot that has to be done, but we have a role. A lot of it's going to be supporting research policy directives, but it’s an all-of-state response that’s going to be required if we really want to make a difference.

NJ: Well, let's talk about that. I mean, what are some of the policies that can be pursued to address these disparities?

TD: Yeah. You know, that's really tough. Obviously, if you said what could I do—people ask me if there’s one thing that I could do, though it’s not really one thing, what would you do? I'd say give everybody good jobs, good education, and access to health care.

NJ: That seems more like an outcome than a policy.

TD: Well, right, it’s an outcome. Those things that lead to those issues would be ideal, if we can do it. But certainly fighting endemic racism is a huge one that we're committed to. Making sure that as a health department we fill the gaps in access where it's not met.

One of the main roles of the health department is to fill the gaps in the health system. Whether it's for family planning, whether it's for treatments, for STDs or other illnesses—making sure that we have chronic-disease screenings. So there’s a lot that we do.

But I can tell you what's going on right now in the health-equity division. We have been very active, the state's community, working with (and)making sure especially in black churches that we have health messaging and access to blood-pressure screening and chronic-disease health management, that sort of thing. (Preventative Health and Health Equity Division Director Dr. Victor Sutton) has been really innovative—and with barbershops, with the counseling as an access point for health care, community-health workers trying to improve health outcomes.

So there's a lot in the health sphere that we're trying to do. But obviously, it's a complicated sort of thing. But we'll continue to look at policy issues and support others and other parts of government to give input. … How do you improve access to care and how do you fight endemic racism, which is a huge thing, working to overcome the barriers of trust that understandably exist in the black community as far as engaging the system—the same stuff that we all know.

NJ: Speaking of addressing black health disparity, I think Medicaid expansion is something that, just like many other health-care issues, disproportionately affects black Mississippians. I've seen it suggested in some studies that about half of the Mississippians who would receive health-care as a result of Medicaid expansion would be black. Is that something to pursue to address these inequalities?

TD: You know, that's obviously been a big debate and that's something for the politicians to determine. Wherever we can help identify people that should have access to care, certainly we want to support that.

Where we have that success is going to be with some of the waivers. The Medicaid waiver, the family-planning waiver, things like that. Because even if you don't have Medicaid, you do have access to reproductive-health services, everybody does in Mississippi, if you don't have a certain amount of income, and so there are opportunities. But you know, I think that's a conversation that we need to have.

Through our political process, and our elections, we have not embraced that universal health insurance for a lot of reasons, and some of it is cost, and certainly I understand those concerns.

Liz Sharlot: Can I just say, this is really not just the health department’s decision. I think that question is better aimed at the Legislature and the governor's office, that kind of thing, because that really is not a health department decision.

NJ: I completely understand that it's not the purview of MSDH to decide that it's time for Medicaid expansion, but when it comes to what is needed to address these issues, I mean, that's more of a medical, more of a health question. And I understand the elements of it that are political. But when we're talking about health care, we're talking about the distribution of resources, those are essentially all political questions. So there's an intersection here, right? I'm wondering, if we're talking about how to address health disparity, how to address a lack of access—is extending actual health-care to 130,000 to 140,000 people the suggestion here? This is something that's being studied right now. That's why I asked the question.

TD: You know, so our role, and our commitment is to try to fill in the gaps. And so whatever can—we are very supportive of access to care. However that’s done. And certainly if the political leaders decided on Medicaid expansion, that's something that we would be … so, you know, that'd be great.

With that not being the case, we're proud to work closely with community-health centers and also use whatever resources we can garner to fill the gaps. So, you know, we're committed to access to care however it can happen, and we'll continue to work with our state leaders and also partners to try to make that happen. But obviously that’s a huge issue for Mississippi.

NJ: Well, let's talk about some other health-disparity issues in that same vein. I've seen reports and studies that talk about health-care workers and the health-care system as a whole undervaluing black experiences and suffering from health issues. Is that something that we run into in Mississippi? Are people receiving different treatment based on the same symptoms or the same experiences, and how are we addressing that if so?

TD: Yeah, so clearly we have data across the country that shows that, with that access to opioids, you know, white folks had easier access. We can argue if that's a good thing—I mean, it's a bad thing—well, certainly we were too liberal with opioids and may still be to some extent now.

So there clearly are a lack of cultural understanding, a lack of empathy for a different culture.

And the health system is obviously mostly populated by white folks. So there will be some natural cultural barriers in that. That being said, I mean, one of the best things that we can do and hopefully we'll continue to do is support. I mean, obviously additional understanding, and certainly we've worked to that end and a lot of measures.

But also, getting more African Americans in the health-care workforce, especially in the physician corps. And so, you know, there's great stuff going on, especially with Jackson State, Tougaloo Jackson Heart study, supporting that effort. (Nashville HBCU) Meharry College did a new residency program in the Delta.

So everything we can do to improve the population of African Americans in the health-care workforce is so, so very important. And then the health department, you know, a large portion of our leadership, especially in the health field, are African Americans. And so we're fortunate to have ready access to the black experience through the leadership at the health department.

NJ: Right. Moving through that, there's a broader range of things that would be considered health-care justice. The one that sticks out to me is the food-desert problem that we have in Mississippi, where you have individuals who have very little access to grocery stores, to healthy food, fresh food, vegetables, things like that. To what degree does that contribute to the underlying health problems, and can the health-care system deal with that, or can it just point to it?

TD: Yeah, the food desert issue is really so remarkable and complicated.

I will say with some degree of absolute belief that it's a poverty issue more than anything. And so I think our attempts to do community gardens and farmers markets are certainly useful, but it's a small drop when compared to people's access to resources.

If you're poor, and you have $4 for a meal, it's obvious where you should get your food from versus getting a couple of avocados from Whole Foods. It's in my mind about the poverty issue. And until we fix that, or can at least make that better, you know, us trying to get healthy foods in the community is a noble thing, but it's not a long-term solution.

NJ: So I want to move back to coronavirus specifically and testing particularly. We talked about this a little bit, but I want to really dive into it. You mentioned to a Mississippi legislator that about a third of private testing data did not have racial demographics attached. I've had clinicians reach out to me and mention that when they submit samples to private labs, for example, there's no mechanism to report race, which is something that I know I brought up to you at the pressers. One thing that I want to make sure: the 4,700, those cases, all of those are investigated, and we are certain about the racial data on those, correct?

TD: Right. That’s part of our investigation.

NJ: Right. And then obviously the deaths would follow from that. But when it comes to a full picture of testing penetration across the state geographically and demographically, what progress has MSDH made on that, and when can we expect those numbers to be released?

TD: We get our data through multiple feeds. Coronavirus has been interesting because we have so many different sources of lab data coming in on a lot of this—pieces of paper or faxes—and so you can imagine that's difficult to handle in the electronic age, especially with the thousands and thousands, I mean, 53,000 units in. So that's sort of a lot to manage.

But there is a subset of the data that comes through our traditional partners that does have race data in it, and we will be able to pull that out. And it does seem like it probably will be a representative sample. So there's not a built-in extraction mechanism for that data, but we can build one, and we'll plan to pull that out and provide that hopefully in the very near future.

Like we had the other things, with racial data, it just takes a while to build it, but we’re committed to doing that.

NJ: Now also talking geographically, which I think has a correlation there, are we looking to get information on testing penetration on a geographic, county basis?

TD: Yeah, absolutely. Definitely, that’ll help us understand where to deploy resources so that too is going to be a critical question.

NJ: Right. Something that I've noticed that seems relatively unique to Mississippi are its gender disparities. Around 60% of our reported patients are female. Elsewhere in America and the world it's the exact opposite. Men get more visible, more impactful cases, and certainly men die more. I haven't seen a gender breakdown for our COVID-19 deaths. Do we know what that proportion looks like?

TD: And that’s a really good point. We don’t know exactly why. There have been several different proposed reasons for the sex imbalance. One of them that is probably most relevant is going to be who works in public-facing (jobs), especially like in restaurants and in convenience stores like that. A lot of that is women. A lot of black women.

NJ: And that’s what I was wondering, is there a correlation? Is there a correlation between the racial disparities and the gender disparities? Is that your understanding? Are you familiar with the numbers? Are more women dying or are more men dying?

TD: Yeah. More women are dying. We’ll get that up there (on the MSDH website).

NJ: Right. You mentioned public-facing jobs. To what degree do the different racial disparities in the workforce and in who works in certain sectors—who works in an office and who works a service job—contribute to some of the disparities we're seeing?

TD: That's a good question. We don't have the answer to it yet. Certainly it's something that we will investigate as we go through. You know, losing social distance is a question. You can do telework for these questions, right, so you've been busy. I know you've been able to telework by and large. Those are all future questions that we're going to have to do a detailed analysis, but that certainly does make sense.

NJ: What is the biggest step that you are taking right now to address this racial disparity and to flatten this curve in the black community specifically?

TD: Probably the biggest specific thing for the black community is we were doing a full-on funnel penetration with messaging using black leaders, African American-focused communications using the faith community, black churches, and also using other innovative places like Headstart centers and places that have a real prominent role in the community.

That's probably the most specific thing, but probably one of the most impactful things is going to be as we go forward and start doing enhanced testing around individual cases that will especially help folks in black communities because that will automatically deploy around where the case burden is, and we can better penetrate testing and infection-control efforts by that effort. Although it’s not specifically African American-targeted endeavor, it will be in fact, because that’s where the case burden is.

State intern Julian Mills contributed to this report.

Read the JFP’s coverage of COVID-19 at jacksonfreepress.com/covid19. Get more details on preventive measures here. Read about announced closings and delays in Mississippi here. Read MEMA’s advice for a COVID-19 preparedness kit here.

Email information about closings and other vital related logistical details to [email protected].

Email state reporter Nick Judin, who is covering COVID-19 in Mississippi, at [email protected] and follow him on Twitter at @nickjudin. Seyma Bayram is covering the outbreak inside the capital city and in the criminal-justice system. Email her at [email protected] and follow her on Twitter at @seymabayram0.

More stories by this author

- Vaccinations Underway As State Grapples With Logistics

- Mississippi Begins Vaccination of 75+ Population, Peaks With 3,255 New Cases of COVID-19

- Parole Reform, Pay Raises and COVID-19: 2021 Legislative Preview

- Last Week’s Record COVID-19 Admissions Challenging Mississippi Hospitals

- Lt. Gov. Hosemann Addresses Budget Cuts, Teacher Pay, and Patriotic Education

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus