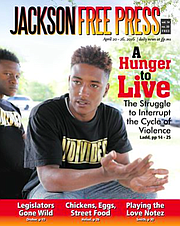

Attorney and activist Rukia Lumumba addresses attendees of a public forum on gun violence in Jackson at the Mt. Helm Baptist Church in downtown Jackson on Jan. 20, 2020. Photo by Seyma Bayram

Veteran educator and Jackson native Edith Pitchford stood before a crowd inside of Mt. Helm Baptist Church in downtown Jackson on Martin Luther King Day. She reflected on the difficulties of seeing her students walk along a forked path over the years. Though many worked toward, and achieved, secure and successful lives, she noted that some fell into a life of crime.

"How do I as a teacher help?" she asked several dozen community members, who had convened inside Jackson's first black church for a public forum on the multi-faceted issue of gun violence in the city on Jan. 20.

"I know how to help my students individually, but when you have about 70 to 100 students, how do you help them?" she continued. Pitchford acknowledged that everybody makes mistakes and cited the frustration of watching people struggle, even those who had made serious efforts to turn things around. "You can't reach everyone," she added, before inquiring about community services to which she could refer at-risk students. "I'd like to know where to start."

Recognizing the Conditions for Violence

John Knight, an anti-violence activist with the Strong Arms of Jackson—Jackson's credible-messenger and violence-interruption strategy—and panel member at the forum, responded to Pitchford. "Well first, to start, by loving them like y'all did me," Knight said.

The formerly incarcerated Knight grew up in the Washington Addition neighborhood, like Pitchford. They were next-door neighbors when Knight was growing up, though Pitchford eventually moved to the nearby town of Terry. He has been mentoring at-risk young people in Jackson since his release from prison the last time.

Knight described the challenges of reaching children in Washington Addition and other impoverished, at-risk neighborhoods in Jackson today. He spoke of the breakdown of trust and interpersonal relationships in the community since his childhood and a culture of fear among residents due to elevated levels of crime. He pointed to the ongoing disinvestment in these neighborhoods, which means a lack of enrichment programs for kids, programs that existed when he was growing up.

"These kids now, age 25 and under, they're coming up in a different fashion, they're coming up on a different kind of love than we came up under. They love the streets more than they're loving their mom, loving their brothers, loving their cousins," Knight said. "... They have a lot of different things to get into, a lot of different drugs they're experimenting on, a lot of younger parents who wasn't raised right to love their kids or show their kids how to accept love."

"Some people don't know how to go to them, some people don't know how to get them to really understand that the situation that they're in can be changed," Knight added. He emphasized the importance of people from similar backgrounds, like himself, coming back to the community to mentor young people and dissuade them from going down the wrong path.

Knight acknowledged the severity of violence in Jackson, but he stressed that it can be fixed over time. One solution, he suggested, was to fund community centers and youth-enrichment programs in impoverished areas like the Washington Addition.

"There's different programs we need to get the city council and the government to fund, to funnel more money into programs for kids," Knight said. "We have centers, we have everything we need to not get in trouble. ... So we have to fix that, and maybe then we can fix some of these problems with these at-risk juveniles."

The breakdown of relationships, poverty, and hopelessness were among some of the barriers to ending gun violence and building healthier communities, said Knight and others on the eight-person panel, which also included defense attorneys, a prosecutor, anti-violence advocates, a mental health counselor, a police officer and others. But disinvestment in Jackson communities, lax gun-control laws and a failing mental health system—all under the State's purview—all create conditions for violence. So do gentrification, white flight and black flight, they said.

'Challenging the Narrative that Everything Is Our Fault'

Organized by members of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc., and the Mississippi Poor People’s Campaign, the Mt. Helm forum comes on the heels of a deadly year in Jackson. In 2019, Jackson saw 82 murders, a 2% decline from the previous year. Since 2017, homicide rates have increased dramatically in the capital city, jumping from 64 murders to 84 in 2018—a 31% increase. Gun violence has continued to spike in Jackson despite the launch of various joint task forces between local, state and federal law enforcement officials to combat violence.

Both the public and the panelists who spoke at the forum overwhelmingly agreed on one thing: by the time law enforcement arrives, it is too late, a point Jackson Mayor Chokwe A. Lumumba has repeatedly made. Instead, community members, including survivors and families who had lost loved ones to gun violence, shared resources and focused on identifying solutions and approaches to prevent violence from occurring in the first place.

Attorney and activist Rukia Lumumba, another panelist and the mayor's sister, acknowledged that while violence is a systemic issue and Jacksonians have a responsibility to repair relationships and heal their communities from within, that the onus cannot fall solely on them.

"Guns didn't just show up on our block. Most of the people in Jackson are too poor to afford a gun in the first place, but they showed up in our community, just like drugs showed up in our community at mass amounts, being flown in from airports, and ain't none of us on planes," Lumumba said.

"This is not just a problem of our people," she continued. "This is a problem of a system that continues to funnel things into our communities, and we are not doing the job well enough to begin to prevent that from happening in the first place. So we need to look at that, as well as our interpersonal relationships. Yes, we need to improve our education system and begin to take it into our own hands. We recognize that the State is not doing what we need them to do, in any way."

Lumumba emphasized the urgency of challenging gun laws in Mississippi as part of wider efforts to hold state officials accountable in their dealings with Jackson. She pointed to disinvestment in Jackson at the State level in areas ranging from underfunded education—dating back to forced integration, when the State allowed less funding to predominantly black Jackson Public Schools than white-majority schools—to lack of adequate funding to address vital infrastructure needs such as roads and even housing.

Housing instability, lack of education, the easy accessibility of guns—all of this "creates conditions of violence," Rukia Lumumba said.

How Integration Failed in Jackson’s Public Schools from 1969 to 2017

What you may not know about how Jackson's public schools were forced to integrate, followed immediately by thousands of white families fleeing schools, based largely on back science.

"The gun laws are not Jackson laws, they are state laws. Even when people go to prison, they're normally sentenced by the county, not by a municipality," she reminded attendees, urging them to "challenge the narrative that everything is our fault as Jacksonians" while continuing to carry out their responsibility "to figure out how we take care of ourselves," which requires resources and funding.

Mississippi has some of the most liberal gun laws in the United States. The state's weak gun laws have earned it an "F" ranking with the Giffords Law Center, a public-interest law firm that advocates for tighter gun legislation. In Mississippi, people can openly carry guns on their person or keep concealed guns in their cars without a license. They can also carry concealed weapons outside vehicles with a permit.

Implementing background checks, overhauling the state's permitless carry legislation and funding proven "violence intervention programs" are among some of Giffords Law Center's recommendations to Mississippi lawmakers to end the epidemic of gun violence there.

Supportive Services, Violence Intervention

The forum highlighted the lack of mental-health services in Jackson and throughout the state as a contributor to the cycle of violence. Last September, U.S. District Court Judge Carlton W. Reeves ruled that the State of Mississippi violates the civil rights of those who suffer from mental-health issues. Among other revelations, the four-week-trial revealed that Mississippians were being institutionalized in State-run hospitals because of the lack of community-based supportive services in their own cities and towns. Intensive community-based treatment, aimed at people with severe mental-health issues that have not shown improvement through outpatient programs, do not exist in 62 of Mississippi's 82 counties.

The lack of supportive and mental-health services extends to those struggling with drug-addiction issues or those who are imprisoned.

Panelist Dr. Damien Thomas of Resilience Counseling LLC pointed to the misguided notion of rehabilitation in prisons and jails that "if (inmates) break, they've been rehabilitated."

"That is a lie," he said.

Denise Coleman, a leader with the People's Advocacy Institute who herself served 37 years in prison, highlighted the need for additional supportive services for those re-entering society after being incarcerated. She detailed her own struggles to find housing, work and even cash checks upon her release because she had no identification. It took Coleman six months to obtain a state ID, her birth certificate and Social Security card after her release.

Though Coleman's re-entry has been successful, she noted that for many people who are returning to their communities, these kinds of seemingly minor bureaucratic barriers too often result in significant consequences. They may end up in the system because they cannot pursue lawful employment or find a home without the necessary documents, on top of other stigmas.

Knight said those who had been through the criminal-justice system and those who had committed acts that hurt their communities had a responsibility to help heal those communities. He added that they were well-positioned to do impactful work around violence prevention due to their shared background with at-risk young people and adults.

"A lot of times (at-risk young people) don't want to understand an educated person (who) comes to them with metaphors and papers and statistics," Knight said. "They don't want to hear it because they didn't go to school. They didn't go to school so they don't understand it, so you're going to lose their concentration. You have to keep them listening to you, and also you've got to get them to believe in you."

Knight's comments are in line with a credible-messenger and violence-interruption strategy, Strong Arms of Jackson, which is deep into its fundraising stage but already carrying out initial work in the city.

The JFP's 'Preventing Violence' Series

A full archive of the JFP's "Preventing Violence" series, supported by grants from the Solutions Journalism Network. Photo of Zeakyy Harrington by Imani Khayyam.

Once trained, credible messengers do on-the-ground counseling to dissuade at-risk individuals from participating in crimes, especially after violence has already occurred and the chance of retaliatory violent acts is high. The model requires that messengers are people who have been through the criminal-justice system themselves—as perpetrators of crimes or as victims, though frequently both—and come from similar circumstances and communities as those they are trying to reach. That means their advice is more likely to resonate with the people who need it the most.

The Strong Arms of Jackson program also plans to invest in other community resources by offering job training, employment opportunities, youth enrichment programs, and conflict-resolution training.

Studies from New York City, Chicago, Baltimore and other cities show that with enough funding and a full-time staff of trained credible messengers and violence interrupters, the model works at reducing violence. This year, the City of Jackson has invested a small amount of money toward funding the Strong Arms of Jackson program, as its leaders continue to seek other sources of funding, including philanthropic contributions. But funding remains the biggest obstacle to the program's viability and impact.

Cheryl Turner, a panelist and member of the nationwide grassroots movement to end gun violence Moms Demand Action, commended the forum for bringing together various stakeholders in the community who want to address the root cause of gun violence. She urged those in attendance to continue nurturing the connections they had made that day and translate it into meaningful action, by helping the young people and adults who are involved in the gun violence epidemic.

"Some of these kids are just scared, and they grow up in neighborhoods where there is no hope, and where there is lack of hope and a lack of opportunity, and a lack of resources, then you get what we got," Turner said.

"What we've got to make sure is we all stick together, and make sure that we connect these dots that are here."

Read the JFP's award-winning archive of solutions journalism on preventing violence at jacksonfreepress.com/preventingviolence. Follow City Reporter Seyma Bayram on Twitter @SeymaBayram0. Send story tips to [email protected].

More stories by this author

- City Announces Robinson Road Repaving Project; Stay-At-Home Order Still in Effect

- City of Jackson Sues Canadian National Railway Over Blocked Railroad Underpass

- Mayor Lumumba Revises, Extends Jackson Stay-at-Home Order

- Mississippi Justice Institute Sues Mayor Lumumba for Open-Carry Order

- Jackson Attorney with COVID: ‘A False Sense of Protection Here’

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus