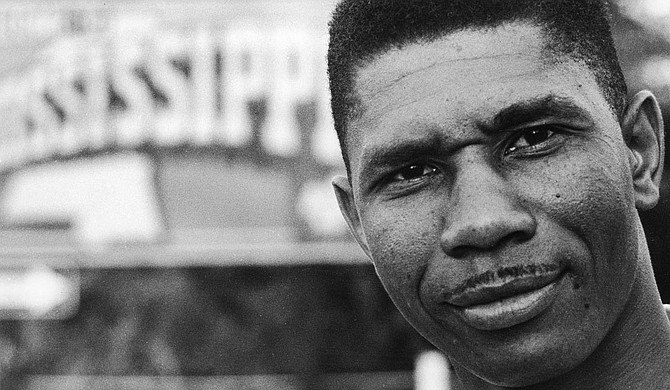

Former Mississippi NAACP Field Secretary Medgar Evers, would have been 95 on July 2, 2020, but died before his 38th birthday after a white-supremacist sniper shot him at his Jackson home. Photo courtesy FBI.gov

As a young girl growing up in Jackson, Miss., in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Reena Evers-Everette, the second child and only daughter of the iconic civil-rights activist Medgar Evers, had all the opportunity in the world to hate white people.

Before the assassination of her father in 1963, which made him a black-freedom martyr nearly five years before Martin Luther King Jr.'s murder, someone threw a Molotov cocktail at the Evers' house. It went under the car.

Evers' wife, Myrlie, was able to get the bomb from underneath the car with the help of a neighbor before it did any damage. When her father came back late that night, he hugged Reena to say good night, and she asked him, "Do all white people hate us?"

The answer he gave her that night marked who she is now.

"He called me Sunshine (his nickname for her), and he said, 'There is good and bad in every race; always look for the good.' So that has stuck to me," Evers-Everette said.

Although her mother took the children out of Mississippi after her father's murder, Evers-Everette returned to Mississippi in 2012. She is now the executive director of The Medgar and Myrlie Evers Institute in Jackson, set up to extend both of her parents' legacies. She is also a fellow with the W.K. Kellogg Foundation Community Leadership Network, a multi-racial group working together to face and heal racial division and inequities.

'Divisive Flag' Comes Down

When the signature of Gov. Tate Reeves put an end to the 126-year reign of the former Mississippi flag with the Confederate emblem on June 30, it was two days before what would have been the 95th birthday of Medgar Evers.

That his daughter was at the signing ceremony—she wore a black mask with "EVERS" in white lettering—would surely make him proud, having lost his life to an assassin's bullet in 1963 in his fight for racial justice in Mississippi.

"He, along with so many ancestors who have been in the fight to eradicate injustices, was on such a high heavenly cloud of joy, even though it was not within their lifetime on earth. I felt the support in the spirit of my father that day," Evers-Everette said of the bill-signing ceremony.

Her father was a tireless fighter for civil rights. He was a World War II veteran who returned to become an activist who worked to overturn segregation at the University of Mississippi and expand voting rights for African Americans.

Evers died June 12, 1963, as he returned from a National Association for the Advancement of Colored People meeting; he was its first field secretary in Mississippi. A white Ku Klux Klansman and Citizens Council member, Byron De La Beckwith, shot him with an Enfield 30.06 sniper rifle as he hid in honeysuckle bushes nearby.

The fallen fighter left behind not only a loving family, but a legacy of courage in the face of severe opposition.

"Medgar was going outside of Mississippi, raising money and talking to people (about) how it was here," Minnie Watson, the long-term curator of the Medgar Evers Home Museum, told history.com. "So the change was coming, and those who were against what was happening could see it. And people were saying, 'Medgar Evers, your days are numbered,' because he had rallied the young people, and he was making people aware of what your rights are for being the citizens of this county."

The Home of a Hero

When Medgar Wiley Evers died 57 years ago, it was just 20 days shy of his 38th birthday, and he left three children—James, Reena and Darrell—as well as his wife, Myrlie, behind.

Though born in Decatur, Miss., a town in Newton County with a population fewer than 2,000, Evers lived at the end of his life at 2332 Margaret Walker Alexander Drive in Jackson.

This reporter went to his home and saw the words commemorating the classification of the house as a national historic landmark by the United States Department of Interior, National Park Service in 2016.

"This home possesses national significance as the home of Medgar and Myrlie Evers, both important in the Civil Rights Movement," the placard said. "As field secretary for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Medgar Evers was at the forefront of every major civil-rights event, in Mississippi from 1955 until his assassination in 1963."

A bill signed into law in March 2020 added the home to the list of national monuments. "Historians say the killing of Evers was one of the catalysts for the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964," The Guardian reported about the designation. Visitors can view exhibits about Evers' life, death and work, as well as family photographs and memorabilia.

Tougaloo College Archivist Tony Bounds led tourists from Barnard College in New York on a tour of the home, as an April 2019 blog post at mssemester.wordpress.com described. He told them that Evers and his family lived in threat of terror and that the roof of the house was made of gravel to protect from "Molotov cocktails," handmade bombs white supremacists often used then to terrorize Black people.

The family did their best not to be predictable in their movements, changing the route to and from the house, not even having a specific grocery day.

Other security measures included having the children sleep on mattresses on the floor, Bounds told the visitors, "so they could roll off in the event that the house was shot at or bombed." They also turned off the porch light so no one would see Evers exiting the car, and did not get out of the vehicle on the left side.

But Beckwith did see him that night, as one of the Barnard visitors blogged. "(As) Bounds traced the steps of Medgar Evers that night, and the flight of the bullet, I thought about the notion of a house literally designed to protect a black family from violence," the blogger noted. "The irony (is) that when Evers was shot, Mrs. Evers was inside watching JFK give a speech on civil rights on TV, that the shirts he was grabbing from the trunk read 'Jim Crow Must Go.'"

Beckwith was finally convicted 31 years after he assassinated Evers under his carport, in 1994.The same year, the U.S. Congress voted to rename the main post office in Jackson after Evers. It was a voice vote without recording who voted for or against the renaming.

Two years prior to the overdue justice, the Medgar Evers Statue Fund Inc. put up a $55,000 statue in Jackson in Evers' honor on June 28, 1992, dedicated to "everyone who believed in peace, love and non-violence" with a call to "keep the torch burning." Jet magazine noted the cost in its July 11, 1992, reporting on the unveiling.

This reporter went to the Medgar Evers Boulevard Library, Jackson, to see the statue of the hero on June 25, but it was hard to find. The dark color of the statue blended with the dark green leaves on trees around the beautifully kept and serene boulevard just blocks from the home where he died.

In October 2011, the Jackson Free Press reported the decision of the Jackson City Council to change the name of the city's airport to Jackson-Medgar Wiley Evers International Airport, in recognition of the significant role he played in the history of the state as a civil-rights pioneer.

From Decatur to Activism

John Spann is a history graduate of Mississippi State University and has been working at the Two Mississippi Museums since its opening in 2017. He is one of the curators of education programming. With dreadlocks and wearing a black T-shirt and white shorts, he waxed eloquently as he took this reporter, who visited the Civil Rights Museum to find out more about Medgar Evers, down memory lane.

On July 29, a day before the new legislation rejecting the state's flag passed overwhelmingly, Spann emphasized not just Medgar Evers' death but the activism that led to it and continued afterward.

Spann said Smith Robertson Museum and Cultural Center in Jackson—in the location of Jackson's first elementary school for Black children, built in 1894—has an exhibit on his early life in Decatur.

"It talked about how he grew up with his mother (Jesse) and father (James) and other siblings and cousins, their humble beginnings, what he learned from his father, being a man, how it was growing up in the rural south," Spann said. "He wanted to follow his brother Charles into war, and he lied on his application because he was not old enough. He was not 18."

Medgar Evers saw action in Liege and Antwerp in Belgium; and Normandy, Le Harve and Cherbourg in France.

Spann said that going to War World II was pivotal in Evers' evolution into a foremost civil-rights activist in the state. The racist and near-violent opposition he experienced as he wanted to register to vote at age 21 made things personal for him.

"He and his brother Charles wanted to go and register to vote in Decatur, and they were met with white men with guns," the historian explained. "They actually left, and they have a plan to come back with their guns. But before any violence happened, they realized that it wasn't going to be a good outcome for anyone."

Medgar Evers met his wife, Myrlie, at Alcorn College (now Alcorn State University), as a student in the historically Black college. They moved to Mound Bayou in the Mississippi Delta, a historically African American town founded in the late 1800s. There he worked for a Black entrepreneur, Dr. Theodore Howard, who was also an activist, mentor and funder of freedom fighters like Medgar Evers.

Makings of a Civil Rights Hero

Dr. T.R.M. Howard hired Evers to sell Magnolia Mutual Life Insurance Company policies. Medgar visited plantations in the Delta near Clarksdale to sell life and hospitalization policies and collect premiums including from Black people in the Delta, some of them plantation workers. "With Dr. Howard's full backing, he promoted civil rights on these visits," Professors David T. Beito and Linda Royster Beito wrote about Evers in The Hill.

After the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, which legally overturned school segregation—although the state refused to integrate schools until early 1970 after violent resistance—Howard encouraged Medgar to apply to enroll at the University of Mississippi School of Law in 1954 in Oxford. "But the administrators found a pretext to turn him down," the professors wrote.

Instead, James Meredith would become the first Black man to successfully enroll at that university on Oct. 1, 1962, after violent riots of white supremacists left two people dead.

The same university now sings Evers' praise on its website for his work as the first NAACP field secretary in Mississippi, attracting the kinds of attention that ultimately led to this death by investigating violent crimes committed against Black Mississippians and trying to prevent them. UM also praises Evers for helping Meredith enroll. "His boycott of Jackson merchants in the early 1960s attracted national attention, and his efforts to have James Meredith admitted to the University of Mississippi in 1962 brought much-needed federal help for which he had been soliciting," the UM site states.

The piece referred to Evers as a peaceful man who always insisted that violence is not the way.

"Perhaps the greatest tribute can be found in changes noted in Mississippi Black History Makers: 'Ten years after Medgar's death the national office of the NAACP reported that Mississippi had 145 black elected officials and that blacks were enrolled in each of the state's public and private institutions of higher learning," the UM site said.

However, Mississippi voters have not elected a Black person to statewide office since the Reconstruction era ended, followed by the white-run State of Mississippi enacting a variety of laws to keep Black people from voting and progressing economically, as well as requiring segregation by law.

Spann said Evers' NAACP work included the integration of schools, boycotting businesses that want Black dollars but don't want to treat Black people fairly, and fighting for voting rights. He credits Evers for creating NAACP youth councils to get young people more involved in NAACP efforts and also giving them a way to use their voices.

"With the youth council, he organized the boycott of Capitol Street (in Jackson). A major business area, it was pretty much for white only, most of it. But Black people could shop in some stores, but they were not treated humanely," Spann said.

"If you went into a dress shop or clothing shop, and you wanted to try clothes on, they would probably tell you you could not try on clothes, or you were followed around the store," Spann said. "But if you paid your money and you came back and said, 'it does not fit, I want to give it back,' you could not give it back because you were Black."

Spann said white Mississippi wanted to silence Evers "because he was trying to unify, the same way that Martin Luther King was trying to unify. He was not just for Black people; he was for all people, particularly the state of Mississippi."

Mississippi Civil Rights Museum visitors can watch a video about Evers' life, how he got into the movement, his civil-rights work and his assassination. The rifle used to assassinate him is on display as well.

'Love and Opportunity'

People can still tour the old NAACP office on Lynch Street where people had tried to intimidate Evers. "You can see a bullet hole from a gunshot by somebody driving along the street," he said. "People drove through, saw the office, and shot into it. That was a regular day then. He knew that his life was in danger."

Evers even had a dummy office to increase the odds against his assassination.

In admiration, Spann said Evers knew every day that his life was on the line.

"But he still put his shoes on, put on his socks, walked out the door, and put his life on the line for civil rights, knowing that he had kids," Spann said. "He had a lot to lose, a wife and children he loved dearly. But he saw the evolution of the state of Mississippi as a bigger issue. He exposed all the bad things that the repressive southern regime wanted to hide, so he had a target on his back."

After attending the ceremony where Gov. Reeves signed the bill to rest the Confederate-tainted flag, Reena Evers-Everette said Mississippi was taking a long-needed step by retiring the flag that waved over the state that terrorized her father. "That Confederate symbol is not who Mississippi is now. It's not what it was in 1894 either, inclusive of all Mississippians," she told the Associated Press. "But now we're going to a place of total inclusion and unity with our hearts along with our thoughts and in our actions."

Evers' daughter, who watched her father's assassination, told the Jackson Free Press that she wants him to be remembered as "a strong person of faith, a loyal, loving and dedicated father, a civic servant who did not want to be living in a state or nation that is built on hate."

"But," she added, "he wanted to build it on love and opportunity for all. That includes education, economic security and, mostly, equality for all."

Email story tips to city/county reporter Kayode Crown at [email protected]. You can also follow him on Twitter at @kayodecrown.

More like this story

More stories by this author

- City Council Votes on 2022 Legislative Agenda, Wants Land Bank, Water-Sewer Debt Forgiveness Extension

- Who Is the Hinds County Board of Supervisors’ President?

- JPS Starts In-Person Learning Tomorrow, Enhanced COVID-19 Protocol

- City Engineer: Despite Improvements, Severe Winter Storm Could Wreak Havoc

- Mississippi Supreme Court Appoints Senior Status Judge, Justice to Hinds County Cases