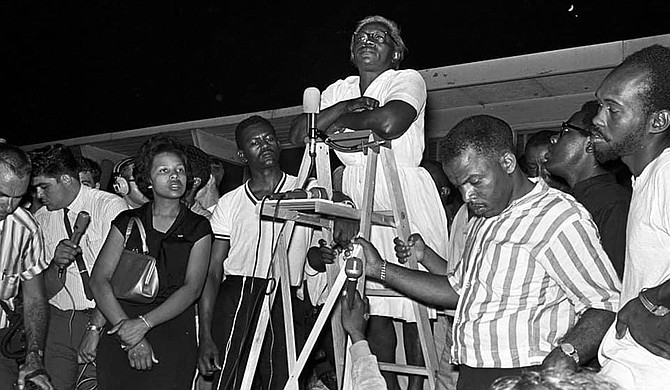

Activist Flonzie Brown Wright, left, and John Lewis, right (holding ladder), listen as Annie Devine, known as the “Mother of the Movement,” stands on the ladder addressing a huge crowd of marchers from across the country in Canton, Miss., in support of James Meredith’s 1966 March Against Fear. Photo courtesy Alabama Department of Archives and History

Our paths first crossed in 1965 in Mississippi. I had seen John Lewis numerous times on TV, especially in 1963 at the March on Washington. Many activists spent a lot of time working in Mississippi, particularly in counties where there was a high concentration of potential unregistered African American voters. In meeting this Soul Giant, as consider him, it was obvious that his commitment to the Civil Rights Movement had been clearly defined. He had suffered much physical harm at the hands of a system defined by the ugliness of racism.

It was also clear to me that John epitomized Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s philosophy that you must not victimize yourself by hating those who perpetrated unequal and discriminatory treatment of the oppressed. John, as he liked to be called, was passionate about using his voice and his body to obtain the right to vote for our people, no matter the cost—and it was extremely costly.

Shortly after the Voting Rights Act passed in 1965, John concentrated his efforts on providing funds for Black people who were running for political office, particularly in counties where there was a Black majority. He founded The Voter Education Project (VEP), for the purpose of funding rides to the polls on election day(s), as well as food for the drivers. It was not unusual for John to come into my hometown of Canton, Miss., and other towns with money for this purpose. Other times, he would send funds to the NAACP office where I worked as branch manager.

When I was elected to the position of election commissioner in 1968, VEP provided financial assistance to me to help increase voting. Thanks to John, we were able to organize, hire and feed drivers to ensure that anyone who was registered to vote would have the opportunity.

After my election, I invited John and Georgia legislator Julian Bond as featured speakers at the first community meeting in the Madison County Courthouse. Incidentally, this is the same courthouse where scores of Black Mississippians had been, in some cases, savagely escorted and/blocked from attempting to register.

During James Meredith's March Against Fear in 1966, John was a visible representative of Dr. King and others. Thanks to the Alabama Department of Archives and History, we have two photos of the historic event. Mrs. Annie Devine, known as the "Mother of the Movement," is standing on top of a ladder addressing a huge crowd of marchers from across the country in Canton in support of the march. John, a number of other supporters and I are featured in this photo. Just after Mrs. Divine spoke, I spoke from that same ladder.

John and I kept in touch over the years. In 2004, he was invited to keynote the 40th-anniversary observance of Mississippi Freedom Summer at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. As Student Affairs Scholar in Residence, it was my honor and privilege to introduce him.

In 2018, he was invited to be the keynote speaker at New Hope Baptist Church during the annual "Back in the Day" Black History celebration. I was surprised that he called me personally to express his regrets that he could not attend because of pressing business "on the Hill."

I will always take with me his legacy as a Soul Giant because he lived and breathed his passion, which was to do all he could, while he could to elevate the cause of human dignity. Even though like Martin, he was short in stature, his words and actions towered well above racism, bigotry and hate.

Allow me to suggest how we can all honor him, whether your paths crossed with John or not. Let's go to the polls in record numbers this November to continue the work he left behind. Every generation has an assignment. He, Dr. C.T. Vivian and Rev. Joseph Lowery, all of whom we lost this year, provided the bridge for us to continue to seek justice for all.

One of the best ways to remember John is to look and listen to the young voices who are speaking out today for human and civil rights. John often spoke to young people of all races and nationalities and challenged them: "Do not get lost in a sea of despair. Be hopeful, be optimistic. Our struggle is not the struggle of a day, a week, a month, or a year; it is the struggle of a lifetime. Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble."

My life is better, and I am stronger because our paths crossed.

Dr. Flonzie Brown Wright is the first African American woman elected to public office in the state of Mississippi in the biracial town of Canton, Miss., in 1968.

This column does not necessarily reflect the views of the JFP.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus