Belk Department Store was closed in Flowood and Ridgeland Saturday, March 28, but Dillard's was open in the same Northpark Mall. Gov. Tate Reeves' executive order leaves department stores in a gray area leading to inconsistency in social-distancing efforts during the COVID-19 outbreak. Photo by Donna Ladd

The concrete shopping jungle known as Dogwood Festival Market looked as much like a ghost town as it could as the sun started to set on a warm spring Saturday afternoon. Barely an automobile interrupted the oddly tranquil parking lots of the popular Flowood, Miss., big-box village, five miles east of the capital city in Rankin County, late on March 28. Only the occasional security officer drove slowly through to keep a watch on mostly chain department stores and specialty businesses, a line-up that looks like most suburban “outdoor” malls across the United States.

This particular Saturday, amid the coronavirus epidemic with 35 cases reported in Rankin County and one death as of this weekend, a hodgepodge of signs on standard white paper dotted the Dogwood stores’ glass doors and windows. The messages on the signs, when read slowly one-by-one on a deathly quiet stroll from store to store, were inconsistent just four days after Gov. Tate Reeves signed an order to supposedly make statewide COVID-19 safety rules match up around the state. He happens to live in a nearby subdivision, which the Clarion-Ledger reported that he tried unsuccessfully to connect straight to Dogwood with a special frontage road.

A couple of the specialty stores looked like they closed in a hurry, perhaps amid confusion. The Children’s Place had two signs crookedly taped side-by-side, one listing limited hours ending at 6 p.m., promising it was following COVID-19 guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and “local government recommendations.” Next to it, another sheet amended that, saying the store was “temporarily closed through Tuesday, March 31,” which would be only a week after Reeves signed his executive order. Nearby, Lane Bryant displayed two similar, conflicting signs, but without a reopening date.

Home Goods, with a lonely display of Easter bunny rabbits waiting unsold on the other side of the glass, was straightforward, making no promises or showing any need to explain: “This Store is Currently Closed. We Apologize for Any Inconvenience.” Bath & Body Works took a similarly straightforward approach. A baseball throw away in the nearby Market Street Center, JCPenney was also closed up.

The department store Belk, based in Charlotte, N.C., had a cheery red-and-white sign standing on the sidewalk: “Buy Online, Pick Up in Store.” Except you couldn’t, because the printed-out signs taped on its glass indicated the store was, in fact, closed. Across Highway 25, Target, Kroger and Lowe’s were open to in-store business, due to selling what are considered “essential” groceries, pharmaceuticals and building/repair supplies.

Nearby craft-supply store Hobby Lobby was also open with a sign telling customers to stay distant from each other, although its competitor, Michael’s, was closed nearby. The day before, Hobby Lobby's Oklahoma corporate office had closed stores in that state because Republican Gov. Kevin Stitt had ordered all non-essential businesses to close there to help flatten the COVID-19 curve, which Reeves has declined to do in Mississippi.

Most of the Flowood restaurants seemed to be following Reeves’ executive order that limits dining establishments to 10 people at once for sit-down services, telling them to close completely if that is impossible. His order allows dining establishments to offer take-out and curbside service, and the Jackson suburbs were seeing a decent number of people doing just that leading up to the Saturday dinner hour. Some servers—acting more like carhops of old—were wearing gloves, and others weren’t. Still others hung out in close proximity to each other outside on breaks or while walking back inside, with no apparent effort to social distance.

At least in the Mississippi county where the governor lives, Tate Reeves’ statewide effort at COVID-19 safety precautions were a hodgepodge of mixed messages and responses four days after he signed it.

What the Executive Order Did and Didn’t Do

The Mississippi governor emailed his four-page order late afternoon on Tuesday, March 24, in the wake of criticism on social media about crowds of Mississippians seen throughout the previous weekend hugging for selfies on Gulf Coast beaches; packed into a home-cooking buffet restaurant in Ridgeland at communal tables; bartering for used items in a large Rankin County flea market; and bidding at a car auction up in Tupelo—all with no apparent social distancing to avoid transmission of COVID-19 as the virus was building exponentially in Mississippi.

Reeves began the first section of his order with his basic rule for stopping the spread of COVID-19—until April 17, 2020, it read: “Mississippi residents shall avoid social and other non-essential gatherings in groups of more than 10 people where the gatherings in a single space at the same time (sic) where individuals are in close proximity to each other.” The next sentence lists exemptions to that rule: “This does not apply to normal operations of locations like airports, medical and healthcare facilities, retail shopping including grocery and department stores, offices, factories and other manufacturing facilities or any Essential Business or Operation as determined by and identified below.”

That section then lays out Reeves’ rule tailored to dining establishments and bars: They must suspend dine-in service unless “able to reduce capacity to allow no more than 10 people to be gathered in a single space at the same time where individuals are in (sic) seated or otherwise in close proximity to each other.” But he then “highly encouraged” dining facilities to do drive-thru, carryout or delivery services, rather than close as a number have done nearby in the capital city, with some restaurateurs like Jeff Good of the Mangia Bene group saying they did not believe they could protect their workers and their customers under the circumstances. Reeves also ordered no visits to health-care facilities unless to provide critical assistance or for end-of-life visits, or when the facility's supervising physician or "supervising healthcare professional" allowed it.

The rest of Reeves’ order did two things: It codified a long list of “essential businesses and operations”—including gun shops, vehicle rental agencies, and vague catch-alls like manufacturers of “products used by any other Essential Business or Operations” and “services related to financial markets.” In a later press conference, he said he drew those essential businesses and operations from a Department of Homeland Security list, but his list contains items not on the federal document.

As written, those “essential” businesses are exempt from what is really the only “order” in the governor’s document that isn’t about health-care visitation—a limit of 10 people in “social or other non-essential gatherings.”

“[A]ny Essential Business or Operation providing essential services or functions may operate at such level as necessary to provide such essential services or functions and shall not be subject to any 10 person gathering limitation or any other limitation or restriction inconsistent with this Executive Order,” Reeves states. He added that those on the essential list “shall take all reasonable measures” to comply with CDC and the Mississippi Department of Health standards, not further defining “reasonable.”

But, also as written, “locations like airports, medical and healthcare facilities, retail shopping including grocery and department stores, offices, factories and other manufacturing facilities” are also exempt from the 10-person rule, and Reeves’ order imposes no other social-distancing requirements on them.

The part of the order that got many local officials up in arms immediately, causing some to re-do their local rules, was the provision that local officials could not adopt any rule “that imposes any additional freedom of movement or social distancing limitations on Essential Business or Operation, restricts scope of services or hours of operation of any Essential Business or Operation, or which will or might in any way conflict with or impede the purpose of this Executive Order.” Such conflicted orders would be “suspended and unenforceable during this COVID-19 State of Emergency.”

But, most of the orders Mississippi mayors had put into place were focused on the types of local businesses, especially restaurants, that Reeves’ order did not deem “essential” enough to exempt from the 10-or-fewer rule with their employees required to return if they could not do their work at home.

Reeves quickly assured mayors like Chokwe Lumumba of Jackson and Robyn Tannehill of Oxford that their rules to date were fine under his order, calling his document a “floor” that they could add to if needed. But, again, that floor only applies to the limited number of non-essential businesses that are defined in the order—restaurants, presumably small retail stores, non-medical fitness businesses and places such as parks. Local authorities might also impose curfews, for instance, but not on a person traveling to participate in an essential business or operation.

On Thursday, Reeves issued an addendum to his order essentially restating the original language: Essential businesses and operations, as he defines them, are exempt from the 10-person rule, and the governor codified no other social-distancing requirements. When it comes to essential businesses and operations, local officials can’t impose any additional restrictions. Only MSDH and the Centers for Disease Control can preempt his order protecting those operations.

The language of the executive order taken as a whole, as a result, leaves department stores like those in Reeves’ home county in a complicated and inconsistent gray area as was apparent in Flowood on Saturday. And that lack of conformity worries both people who work in those stores, as well as public-health experts.

Department Store Associate: Language Is Too Broad

The day after Reeves issued his executive order on March 24, Mary Thomas* heard from her Central Mississippi employer that she and her co-workers would soon be headed back to work. Thomas, who asked not to be identified by her real name due to potential retaliation, is an associate at a major department-store chain with many locations in Mississippi. Within 24 hours of the original order going public, word from corporate came down that the stores would open back up in a week or so because the governor’s order had cleared the way.

The reason? That language up top vaguely including “department stores,” “offices” and “factories” in a list of clearly more critical services such as medical facilities and grocers to which the 10-or-fewer rule did not apply, Thomas told the Jackson Free Press after reaching out to express her concerns about what the order could mean to her and co-workers.

“The way that section is written,” Thomas said of Reeves’ clause mentioning department stores, “that umbrella could mean that stores like Belk, JCPenney and others fall under his criteria (for remaining open).”

Thomas said her long experience working in retail tells her that corporations could well argue that the governor’s specific language gave them a loophole in which to stay open, or open back up. She referred specifically to this clause as a way even department stores could open back up, even if they only really sell unessential items.

“I’m sure companies have people looking at it state-by-state to see what that means for areas that don’t have a direction that is clear,” she said in an interview. “The problem with our area is that it is listed too vaguely to be clear on what would be considered ‘essential.’ It wraps us (department stores) into a larger group that are based out of necessity.”

Thomas said that she’s concerned the language could offer too much leeway for legal interpretation. “It’s too broad,” she said.

She emphasized that her primary concern is safety for herself and her co-workers, especially with Mississippi’s high per-capita rates of COVID-19 infection and increasing deaths. “I worry about my associates,” Thomas said. “I know personally that a lot of people in my company care for elderly or are elderly themselves, or work with people in the health industry,” she said. “Bringing that group back puts everybody in that building at risk without even opening the door to the public.”

Her company has not discussed with workers a way to either limit the number of customers allowed into a store at a time or a plan for distancing within the workplace, not that either of those are required in Reeves’ order, which explicitly says that his 10-person rule does not apply to department stores.

On Saturday, the Flowood Hobby Lobby’s front-door sign (which happened to be taped on the door that automatically moved when you walked up, making it hard to read) only said, “Protect yourself and others. Please follow the CDC recommendation of keeping a minimum of 6 feet between you and others.” Through the glass, people were visible standing within a foot of each other.

Public-health experts like Dr. Irwin Redlener of Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, a specialist in public-health disasters, agreed with Thomas. “We are all suffering, the entire country, is suffering from the lack of consistent messages, started at the top, for weeks and weeks," Redlener said last week on an NBC segment following up on the Jackson Free Press’ story last week revealing the contents of Reeves’ order. ... "There is exactly one thing that we can do right now ... The only action we have to do to save lives and to stop the spread of this disease."

In that segment, Tupelo Mayor Jason Shelton repeated his call for a consistent and strong statewide policy from the governor. "The concerns are twofold: If we’re going to flatten the curve, we have to listen to our doctors, to our scientists," Shelton said. "The second is, there’s very little in the governor’s order. Mississippians are being left to the cities and counties to take action, and every one of them [is] doing something different. If Tupelo closes non-essential businesses, it’s sending people by car to neighboring cities, which is exacerbating the problem. … We need consistent and uniform policy from the national and state level. What we’ve seen is the goalposts keep moving."

In an interview billed as "exclusive" with the Mississippi Today website Friday, Reeves framed the criticism of his executive order as political. "They didn’t like the way we defined business. And again, in some of the more liberal jurisdictions, they wanted to shut down every business, and there’s just some things we believe are essential," Reeves said.

In that interview, Reeves also confirmed again the clause in his order saying local officials cannot touch the businesses he listed as "essential" in the document. "They just can’t directly do something or outlaw something that is under 'essential services,'" he said.

But that doesn't help employees who feel in limbo in businesses such as department stores, which Reeves did not include in his long "essential" list, but said ordered exempt from his 10-people social-distancing rule. Big companies like her employer, Thomas says, watch closely to see just how much leeway state and local governments will allow and act accordingly. And when they see that a competitor figures out a way to open their doors, they may well follow suit, not just for immediate profit but to preserve their market share.

“That’s when they really start to analyze, what does each area look like?” Thomas said. “What is the executive order in your state, town?”

If the government’s rules are weak, vague or confusing, she said, the corporation can just re-open the doors, with still others following suit.

Revisit the Verbiage, Close it Up and Make it More Specific

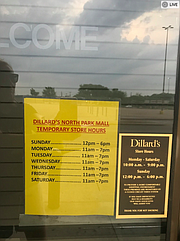

About 10 miles northeast of Flowood in Ridgeland, the Northpark Mall was closing with an almost-empty parking lot at 7 p.m. Saturday, its special pandemic closing time, signs on entrances explained. Like in Reeves’ neighborhood further south, its Belk store was closed, as was JCPenney, pledging to re-open April 2.

But Dillard’s—selling the usual clothing, upscale cosmetics, lingerie and small appliances—was open for business, closing at the same time as the mall after a day of Saturday in-store shopping. Like its locations in other places such as Biloxi in Harrison County on the Gulf Coast, which has seen 43 known cases and one death to date, the Little Rock, Ark.-based department store chain is still open in some Mississippi towns. Ridgeland is just north of Jackson in Madison County, where 37 cases have been reported to date.

CNBC reported on March 27 that Dillards has chosen to remain open in states and localities that have not issued specific orders that would close them; most of its stores are in the southeast, southwest and midwest. CNBC reported that many employees, much like Thomas in Mississippi, are very concerned for their safety and are practically “begging” the company to close the stores.

“We are open with limited hours where not ordered to close by state or local government mandate,” a Dillard’s spokeswoman told CNBC via email. “We are promptly cooperating with any such actions.”

On their signs, the various retail stores from Flowood to Ridgeland promised different dates that they planned to re-open, most of them between now and Easter, which is April 12 this year. That is also the date President Donald Trump had said he really wanted America to move past the fear of COVID-19, and get back to work. He changed his mind Sunday, saying at a press conference that Americans should stay at home, if they can, for another 30 days due to public-health advisers’ warnings.

Many experts, in fact, say that the only way to really contain the epidemic is by taking strong measures to limit contact between humans and with items that can transfer the virus, such as surfaces in high-traffic areas—the metal on doors, plastic displays—that many different people touch and where the virus can live for hours or even days.

It is time, say people who have studied the problem, such as billionaire Bill Gates whose Gates Foundation funds anti-pandemic research, to go well past limiting groups to 10 people in order to have a serious impact on the epidemic.

But so far, the logic of Tate Reeves seems to reflect the president’s thinking that the economy cannot afford the kind of shutdown that could dramatically reduce the ultimate number of deaths. In his executive order, he spent much more time making it clear what businesses COVID-19 safety provisions did not apply to, than those it did apply to. And the vague language that appears to exempt “retail shopping including grocery and department stores, offices, factories and other manufacturing facilities” from his 10-person rule seems to have created exactly the lack of uniformity of response that experts say is required, and that Republicans like the Oklahoma governor are putting into place.

Reeves’ staff did not respond to a request for an interview. However, on Sunday on Facebook Live, the governor interviewed State Health Officer Dr. Thomas Dobbs with both repeatedly emphasizing that a “shelter in place” order, for which a Change.org petition now has nearly 7,500 signatures, would not be enough to completely stop the spread of coronavirus, an argument that proponents are not making.

"There are those who say, well, let’s just shelter in place for a period of time and the virus will go away, and nobody will get it," Reeves said to Dobbs at one point Sunday afternoon.

COVID-19 Information Mississippians Need

Read breaking coverage of COVID-19 in Mississippi, plus safety tips, cancellations, more in the JFP's archive.

The argument, instead, is that such an order would enforce stricter social distancing and keep the health-care system from being overloaded by a rapid increase in cases.

Dobbs, for his part, emphasized that the strategy, now, rather than a statewide shelter-in-place, is to find and isolate "clusters" in different parts of the state. "If we depend on a shelter-in-place to be a solution, we’re going to be sorely disappointed," he said. "It’s a great intervention to slow things down. But if you’re not coupling with something else, it seems like you’re really setting yourself up for failure and frustration. When does it end? Does it end when the cases are gone? Does it end when the curve bends? That could go on for a long time."

The state health officer emphasized that just because a store is open or considered essential, it doesn't mean you are safe from contracting the virus there. "Just because you need to go Walmart doesn’t mean Walmart is immune from COVID," he said, then clarifying that the State is "not talking about closing Walmart under any circumstance."

Dr. Redlener of Columbia University was direct about his concerns that Reeves needs to shut down more businesses and operations immediately to stop the spread, calling the Mississippi governor's approach "a confrontation with science."

"I can almost guarantee that the people of Mississippi will die because of whatever’s prompting or promoting this idea that the governor has been spreading that somehow he should override appropriate public-health practices. It’s staggering," Redlener said on NBC. "I don’t think we’ve ever seen anything like this before. … Lives are at stake, I can’t say that strongly enough, and I think we need to find a way to get the governor to change his mind."

Mary Thomas, who had not heard an update on when her employer plans to re-open by press time, said the solution for Reeves is to “revisit the verbiage, close it up and make it more specific,” so that corporate legal teams cannot twist it to do whatever they want with too little regard for public safety.

“I get it,” Thomas said. “Everyone's hemorrhaging finances, but the trade-off of lives is far greater than other options. Who wants to be diagnosed and, God forbid, end up in ICU to die alone? I don’t.”

- This source's name was changed by request.

Email editor-in-chief Donna Ladd at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter at @donnerkay.

Read the JFP’s coverage of COVID-19 at jacksonfreepress.com/covid19. Get more details on preventive measures here. Read about announced closings and delays in Mississippi here. Read MEMA’s advice for a COVID-19 preparedness kit here.

Email information about closings and other vital related logistical details to [email protected].

Email state reporter Nick Judin, who is covering COVID-19 in Mississippi, at [email protected] and follow him on Twitter at @nickjudin. Seyma Bayram is covering the outbreak inside the capital city and in the criminal-justice system. Email her at [email protected] and follow her on Twitter at @seymabayram0.

More stories by this author

- EDITOR'S NOTE: 19 Years of Love, Hope, Miss S, Dr. S and Never, Ever Giving Up

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Systemic Racism Created Jackson’s Violence; More Policing Cannot Stop It

- Rest in Peace, Ronni Mott: Your Journalism Saved Lives. This I Know.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Rest Well, Gov. Winter. We Will Keep Your Fire Burning.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Truth and Journalism on the Front Lines of COVID-19

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus