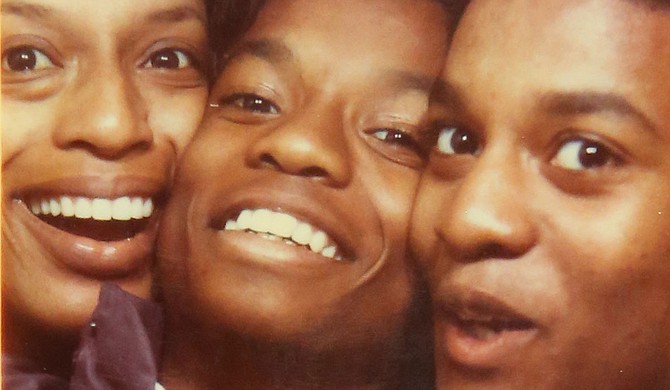

Widowed at 17 and not knowing she was pregnant with her second son at the time, Dale Gibbs was left to raise two boys after a fuselage of gunfire from law enforcement killed her husband Phillip Gibbs at Jackson State on May 14, 1970. From left: Dale Gibbs and sons Demetrius and Phillip Jr. Photo courtesy Margaret Walker Center, Jackson State University

On Feb. 3, 1964, a white driver, Jesse R. Aldridge, slammed into Jackson State College student Mamie Ballard as she was walking along Lynch Street on campus.

At the time, John R. Lynch Street ran through the middle of what is now Jackson State University. White motorists took advantage of the route to taunt students with racist epithets, throw objects at them and threaten to hit anyone in the crosswalk.

With an aggressive tenor, the ensuing student demonstrations demanded justice for Ballard, who survived, and that Lynch Street be closed to traffic.

Protesting Persistent White Supremacy

The Ballard incident was one of many student demonstrations at the public and historically black college. Informed by the modern civil rights and Black Power movements, Jackson State students organized in the 1960s to protest persistent white supremacy in the state and on their campus. Those demonstrations began annually in earnest in 1964.

Each spring, protesters became increasingly demonstrative against aggressive actions aimed at them. In 1970, that included a dump truck that was parked in the middle of Lynch Street, a few blocks from campus, and set on fire.

Although the evidence did not indicate that students had been involved in the burning of the truck, white officials prepared to assert their power with the same violence that has undergirded the American power structure. They sent troops in full riot gear to assault any black person found in the immediate area.

On May 14, 1970, Jackson Police and Mississippi Highway Patrolmen marched on the campus of Jackson State, accompanied by the infamous Thompson Tank, an armored personnel carrier that Allen Thompson, the segregationist mayor, purchased ahead of what he termed the civil rights “invasion” of Freedom Summer in 1964.

When the phalanx of officers reached Alexander Hall, a women’s dormitory, they stood ready to unleash their full force on the peacefully assembled students, who were not protesting at all but were enjoying a Thursday evening as graduation neared. Later asserting the absurd and false claim that a sniper had shot at them from a window in Alexander Hall, the police fired more than 400 rounds of ammunition over 28 seconds in every direction.

Gibbs and Green Killed, Dozen Students Wounded

In the chaos that spilled into the early morning hours of May 15, two men, Phillip Lafayette Gibbs and James Earl Green, were left dead; a dozen young people were wounded in the gunfire; and hundreds of others bear physical and psychological scars to this day.

Phillip Gibbs was a junior political-science major. He had married his high school sweetheart, and they had one son. Unbeknownst to Phillip and his wife, Dale, she was pregnant at the time with their second son.

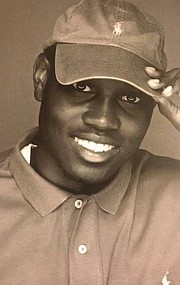

James Green was a senior at nearby Jim Hill High School. He was walking home from his after-school job on the opposite side of the street from Alexander Hall, which meant the police had turned to fire in the other direction from the supposed sniper.

Due to the wanton police attack, Lynch Street was finally closed through campus, and the Gibbs-Green Memorial Plaza now stands in front of Alexander Hall. But, those concessions were not victories and did nothing to lessen the trauma for those who survived.

Graduation was cancelled at Jackson State, and the members of the Class of 1970 received their diplomas in the mail. Civil rights attorney Constance Slaughter represented the families and some of the injured in a lawsuit against the City and the State. The plaintiffs lost their case, and no one was ever charged in the police murders.

From COVID-19 to Arbery’s Murder, Race Injustice Continues

Today, the coronavirus pandemic and the news of continued violence upon black bodies reveal the ongoing nature and impact of the history of racism in the United States.

When considering the insufficient and belated response of state and national leaders that has inflamed the pandemic, the news is clear, especially in Mississippi: The most dangerous implications of the disease disproportionately affect people of color and poor people. In that sense, white supremacy unabatedly assaults marginalized communities.

Now, the Jackson State Class of 2020 faces the possibility of not having their commencement. Not only that, the Class of 1970 was prepared to walk across the stage this year for its 50th reunion and officially receive their diplomas for the first time, and relatives of Phillip Gibbs and James Green were set to accept Honorary Doctorates of Humane Letters on behalf of their murdered family members.

While the administration at Jackson State and our community hold out hope that we will be able to safely gather for these events at some unknown date, there is a real prospect that this modern catastrophe, 50 years later, will prevent us from doing so.

Then came the news that Ahmaud Arbery, an unarmed black man out for a jog, was murdered in Georgia. Activists have turned to the streets to demand that his assailants face trial, but, as the Gibbs-Green survivors and modern proponents of Black Lives Matter understand, justice remains elusive.

Through it all, we must be reminded that state-sanctioned violence aimed at minorities remains a systemic part of America. The ever-present threat of assault continues to prop up white supremacy in this country.

As we prepare for the 50th Gibbs-Green Commemoration at Jackson State, the survivors have lived in its shadow with grace, strength and dignity, and they deserve a legacy of triumph despite that tragedy.

With that in mind, we must demand an honest dialogue around our white-supremacist history and its present-day manifestations. White Americans in particular must be willing to take responsibility and action if our society is ever going to begin rooting out racist power and all its implications.

Robert Luckett, PhD is an Associate Professor of History and the director of the Margaret Walker Center at Jackson State University.

This essay does not necessarily reflect the views of the Jackson Free Press.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.