Meridian, Miss. (AP) — The old civil rights worker was sure the struggle would be over by now.

He’d fought so hard back in the ’60s. He’d seen the wreckage of burned churches, and the injuries of people who had been beaten. He’d seen men in white hoods. At its worst, he’d mourned three young men who were fighting for Black Mississippians to gain the right to vote, and who were kidnapped and executed on a country road just north of here.

But Charles Johnson, sitting inside the neat brick church in Meridian where he’s been pastor for over 60 years, worries that Mississippi is drifting into its past.

“I would never have thought we’d be where we’re at now, with Blacks still fighting for the vote,” said Johnson, 83, who was close to two of the murdered men, especially the New Yorker everyone called Mickey. “I would have never believed it.”

The opposition to Black voters in Mississippi has changed since the 1960s, but it hasn’t ended. There are no poll taxes anymore, no tests on the state constitution. But on the eve of the most divisive presidential election in decades, voters face obstacles such as state-mandated ID laws that mostly affect poor and minority communities and the disenfranchisement of tens of thousands of former prisoners.

By at least one measure, it’s harder to vote in Mississippi than any other state. And despite Mississippi having the largest percentage of Black people of any state in the nation, a Jim Crow-era election law has ensured a Black person hasn’t been elected to statewide office in 130 years. After years of being shut out of state races, Democrats hope mobilizing Black voters and recruiting Black candidates can eventually give them a path back to relevance in one of the reddest of red states.

But sometimes, it can seem that voting rights in Mississippi are like its small towns and dirt roads, which can appear frozen in the past.

Decades after the murders, the narrow county road where they happened still turns pitch black after dark. Pine forests press in from both sides. The only light comes from a couple distant houses and the ocean of stars overhead.

One night in early October we stopped the car along the road and I stepped out. The songs of crickets filled the air. In the distance, I could hear the occasional truck driving past on Highway 19.

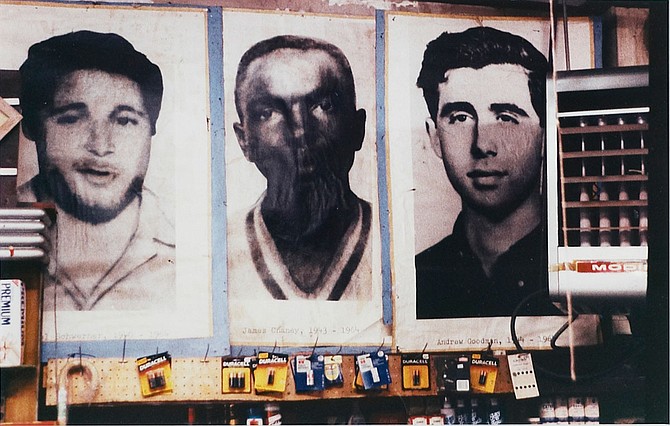

The killers who traveled that road in 1964 were local men - Ku Klux Klan members, a deputy sheriff, a few others. The victims were three young civil rights workers - the oldest just 24 - who had joined a mass campaign that over the coming years helped bring voting rights to Black Mississippi. The men, one Black and two white, were shot at close range. Their bodies were found in an earthen dam 44 days later.

Today, with the presidential election weeks away, three of us on a reporting trip across America wanted to see what things were like in a state where the simple act of voting was impossible for nearly every Black person well into the 1960s. In a year when America has been marked by so many convulsions - a pandemic, an economic crisis, countless protests for racial justice, a virulent political divide - the road trip has been a way to look more deeply at a country struggling to define itself.

We came to Mississippi because what happened here in 1964 was also about elections, and because of the three men murdered on that little road outside the little town of Philadelphia.

The case grabbed attention all the way to the White House. Along with such seminal events as the 1963 murder in Mississippi of Black civil rights activist Medgar Evers, it helped lead to the passage of the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965, which prohibited racial discrimination in voting.

Eventually, so much changed for Black voters in Mississippi.

And yet so much didn’t.

Today, voters in Mississippi face a series of government-created barriers that make it, according to a study in the Election Law Journal in 2018, far and away the most difficult state in which to vote.

Mississippi has broad restrictions on absentee voting, no early voting or online registration, absentee ballots that must be witnessed by notaries and voter ID laws that overwhelmingly affect the poor and minorities, since they are less likely to have state-approved identification. The restrictions have grown even tighter since a 2013 Supreme Court decision blocked many voting rights protections.

“Anything that increases the ‘costs’ of voting - the time it takes, the effort it takes - that tends to decrease voter turnout,” said Conor Dowling, a professor of political science at the University of Mississippi. “And there is evidence that some of these burdens are disproportionately felt by minority voters.”

Mississippi also has widespread poverty. Nearly one-third of Black people here live below the poverty line, more than double the rate for white people, which means taking a day off work to vote can be too expensive.

Then there are the felony voting restrictions, which in Mississippi have disenfranchised almost 16% of the Black population, researchers say — compared to just 5% in nearby Missouri, another deeply Republican state. The Southern Poverty Law Center calls Mississippi's restrictions a holdover from an old state constitution designed specifically to disenfranchise Black voters.

Demarkio Pritchett, who said he was convicted as a teenager of drug possession “and some other stuff,” understands that.

A lanky 29-year-old Black man now out of prison, he lives with his grandmother in Jackson, the state capital, in a poor neighborhood of battered houses with peeling paint, small well-kept homes and empty lots overgrown with trees and kudzu. His grandmother’s house, which manages to be both neat and battered, has an election sign out front for Mike Espy, a Black Democrat running for the U.S. Senate.

Democrats here see hope in candidates like Espy, a former congressman and the first Black Agriculture Secretary, who is focused on registering Black voters. Their long-term strategy hinges on mobilizing Black voters and recruiting Black candidates.

Pritchett's grandmother is zealous about voting. But her grandson can’t vote in Mississippi for the rest of his life. Anyone convicted here of one of 22 crimes, from murder to felony shoplifting, has their voting rights permanently revoked. Pritchett’s only chance: getting a pardon from the governor, or convincing two-thirds of the state’s lawmakers to pass a bill written just for him.

“I want to vote, but they make it so I can’t,” he said, sitting on the front porch with a friend on a recent afternoon. “We just can’t beat the government. We just can’t.”

Distrust of the government runs deep in the Black community in Mississippi, where harsh voter suppression tactics - voting fees, tests on the state constitution, even guessing the number of beans in a jar - kept all but about 6% of Black residents from voting into the 1960s. A Black person who even tried to register to vote could find themselves fired from their job and evicted from their home.

As a result, Black politicians have long been fighting an apathy born of generations of frustration.

Anthony Boggan sometimes votes, but is sitting it out this year, disgusted at the choices.

“They’re all going to tell you the same thing,” he said. “Anything to get elected.”

A 49-year-old Black Jackson resident with a small moving company, Boggan likes how the economy boomed during the Trump years, but can’t bring himself to vote for a man known for his insults and name-calling.

“He’s a butthole,” Boggan said, as a group of Black friends, including one who planned to vote for Trump, laughed and nodded in agreement. "Everybody knows he’s a butthole.”

As for Biden: He and Trump both “got dementia,” Boggan said, and he hates how the former vice president tries to curry favor in the Black community.

“Why does everything he says got to be about the Black? ‘I did more of this for the Black. I’m going to do all of this for the Black,’” he said, angrily mimicking Biden. “Just have them do all this for the American people!”

One man in the group, which was doing construction on a friend’s house on a recent morning, simply refuses to vote.

“Most of the presidents that got in there, they lied all the way,” said Clyde Lewis, a 59-year-old mechanic. “They hurt us more than they help us.”

That kind of talk is painful for Kim Houston.

“Sometimes I think we beat ourselves,” said Houston, the president of the Meridian City Council, the frustration clear in her voice. “There’s this mindset that (voting) doesn’t matter, that nothing is going to change, that the election system is rigged.”

It adds up to a state where plenty of Black people have reached office - by some estimates it has the highest number of Black officials in the country - but many of them are local: mayors, city council members, city officials.

With those officials came significant infrastructure improvements, such as roads paved in Black neighborhoods and sewage systems installed that allowed Black homeowners to finally abandon their outhouses. But in Mississippi, a Black politician can rise only so high, they say, and are kept from those statewide offices.

“When it comes to the positions that really matter, we’re not sitting at that table,” said Houston, a Black woman who also runs an insurance company.

This is why people like Houston, Johnson and countless pastors and activists push so hard to get more Black people to the polls.

Black registration and turnout rates are actually reasonably high in Mississippi. In 2016, for example, 81% of Black Mississippians were registered and 69% turned out to vote.

Roshunda Osby is one of those voters. A 37-year-old certified nursing assistant, she goes to the polls in every election, she said, including local ones.

“If you don’t get out and vote you shouldn’t even have an opinion about what’s going on,” said Osby, who detests Trump for his racism.

“I don’t know much about Joe Biden, but we only have two options, and he’s going to be the better candidate than Trump,” she said, sighing.

Black women are, in many ways, the electoral bedrock of the Democratic Party, a fiercely partisan community known for turning out in force.

But Black women are not enough in a state where politics and race are so tightly interwoven. Mississippi, which is 38% Black, has very few Black Republican voters and relatively few white Democratic voters.

“It almost doesn’t matter if (Black voter turnout rates) are comparable to other states,” said Dowling, the political science professor. “It’s not enough for them to win elections unless it gets better.”

Johnson, the civil rights worker, remembers well how things used to be in Mississippi.

Mississippi could seem like a different country in the years leading up to the civil rights movement. It was far poorer than most of America, it barely bothered to fund some Black schools, it openly treated Black people as third-class citizens.

And Mississippi fought bitterly to deny the vote to Black residents, fearing their numbers would give them political power.

The racism was not subtle.

“I call on every red-blooded white man to use any means to keep the (Black people) away from the polls,” Mississippi Sen. Theodore Bilbo told a group of supporters during his 1946 election campaign, using a virulently racist term. “If you don’t understand what that means you are just plain dumb.”

Johnson was repeatedly refused the right to register to vote. But his anger pushed him to try again and again.

“It made me feel like whatever they try, I was going to knock it down,” he said.

As the civil rights movement took hold, Johnson focused on organizing boycotts of businesses that wouldn’t hire Black people. In 1964, he joined with activist groups who were busing in hundreds of out-of-state volunteers to help organize Black voter registration drives and set up “Freedom Schools” for Black children.

That was when he met Michael Schwerner, a charismatic white 24-year-old who ran a small community center in Meridian with his wife. Schwerner often worked with James Chaney, a quiet 21-year-old Black plasterer and rights activist who sometimes attended Johnson’s church. Chaney and Schwerner traveled to meeting after meeting in this part of Mississippi, encouraging and cajoling people to try to register.

Sometimes, the two would sleep in a car in front of Johnson’s church, fearing it would be targeted in the wave of Black church burnings that swept Mississippi that year.

Then, on June 21, Schwerner, Chaney and a newly arrived volunteer - 20-year-old white New Yorker Andrew Goodman - drove to a little Black church on the outer edges of the town of Philadelphia to meet with witnesses to a KKK attack. The Mt. Zion United Methodist Church, where Schwerner and Chaney had spoken a couple months earlier, had been burned down and its parishioners beaten by a group of Klansmen.

Over the coming hours, the men would be briefly jailed in Philadelphia on trumped-up charges, released and then forced to stop on the highway as they tried to drive home to Meridian. The kidnappers, led by a deputy sheriff and local Klansmen, drove Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman to that narrow country road and shot them at close range.

Johnson was heading to a church meeting in Portland, Oregon on the day of the killing. He stepped off a train to see newspaper front pages declaring the three were missing.

“I knew they were dead,” he said. “If they went that far to take two white boys and a Black boy, I knew somebody was going to die.”

“It looked like there was no good that existed.”

He’s driven down the road a couple times since then, and it reminds him of the continued difficulties that Black people face in Mississippi when it comes to voting.

“I’m afraid the road is just as crooked now as it was then,” he said.

Copyright Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus