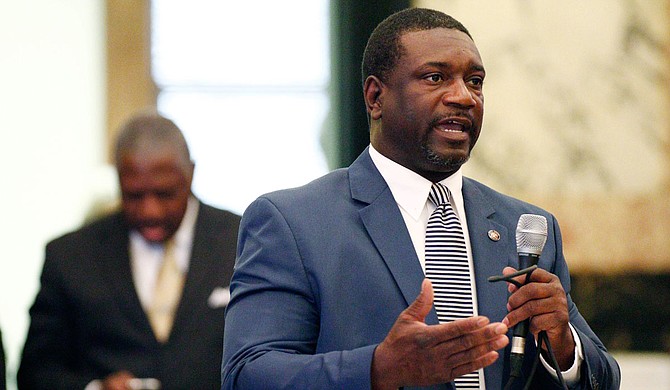

Sen. Juan Barnett, D-Heidelberg, chairman of the Senate Corrections Committee, was only 20 when his father was murdered. Over time, he exchanged hatred for forgiveness—a transformation that guides him as he pursues criminal-justice and parole reform in Mississippi. Forgiveness, he says, heals victims and perpetrators alike. Photo by Rogelio V. Solis via AP

Mississippi Sen. Juan Barnett, D-Heidelberg, was 20 when he buried his father. Willie James Barnett was a victim of murder, a crime that unfolded on Superbowl Sunday in 1990. Barnett would not learn of the tragedy until the following Wednesday; he was 7,000 miles away in Iraq, serving in the U.S. Army in the Gulf War. What followed was the longest flight of Barnett's life, as he returned home to grieve with his mother and his three younger siblings.

"My mother lost a husband. My brothers and sister lost a father. (There was) the possibility of me having to return to my military obligations that I always promised my dad that I would do," Barnett told the Jackson Free Press. His world changed in an instant. Then, he said, "I'm the head of my house."

Barnett spoke tenderly of missed opportunities, of reminiscing with his siblings, of going hunting with his own children as he did with his father, wishing that their grandfather was there to watch them grow. Time has done little to soothe the pain of the loss.

Forgiveness has done more.

"Before I began to forgive the individual, I just found myself stuck in one place ... stuck in anger and bitterness," Barnett said. He wanted extreme punishment for criminals, regardless of the crime or the context. Then, he said, God changed his heart.

"I realized that the only way that I can start to heal from this is to forgive."

Barnett found that forgiveness heals victims and perpetrators alike. That's what inspired him to push for parole reform in his new position as chairman of the Senate Corrections Committee.

Reeves Vetoed Effort

The centerpiece of that push is Senate Bill 2123, a bipartisan vehicle for reforms to Mississippi's parole system. SB 2123 would roll back the clock on Mississippi's parole system, Senate Minority Leader Derrick Simmons, D-Greenville, explains.

"Prior to the 1990s, almost all Mississippi prisoners were eligible for parole after serving 25% of their sentences, or 10 years for sentences of 30 years to life," he wrote in a February Meridian Star article.

That vanished in the 1990s era of punitive justice, when the nation's mass policies of incarceration exploded the national prison population to well over 1,200,000. The result is a state with the third highest incarceration rate in the nation, at 626 per 100,000 in 2018, well above the rate for any country on earth. SB 2123 would revert those parole restrictions, allowing the state parole board to consider shortening the incarceration of thousands of Mississippi prisoners.

Specifically, the bill would extend parole eligibility to nonviolent offenders after they serve 25% of their sentence. Violent offenders sentenced between June 30, 1995, and July 1, 2014 would be parole-eligible after 20 years served of 50% of their sentence, whichever is less.

Violent offenders sentenced July 1, 2014 or after would be parole-eligible after 30 years or 50% of their sentence, whichever is less.

Critically, the bill extends only the eligibility for parole. All incarcerated Mississippians seeking early release from prison must be granted the opportunity by the state parole board. Additionally, the bill specifically excludes habitual offenders—defined in Mississippi law as individuals convicted of three separate felonies "arising out of separate events"—sex offenders, and anyone explicitly sentenced without possibility of parole.

SB 2123 reached the governor's desk in early July, after a lengthy period of conferencing between the two chambers. The final bill passed the House 78-29, and the Senate 25-17.

'All Carrot, No Stick'

On July 8, Gov. Tate Reeves vetoed SB 2123, throwing the bipartisan push for criminal-justice reform, just months after an epidemic of violence struck Mississippi prisons, into doubt. The governor outlined his fears in a Facebook post.

"Right now, you're eligible to get out of prison at 60 unless you're a trafficker, habitual offender, or violent criminal. This totally eliminates those protections. I got countless calls from law enforcement and prosecutors about the risk it creates," Reeves wrote.

The next day, this reporter asked Reeves at his daily press briefing if he trusted the parole board—a body the governor himself appoints—to exercise caution in who it allowed the opportunity of parole. Reeves said he trusted the present board, but added that "I have a maximum of seven years and five months left, serving as governor. And I have no idea who is going to be the next governor."

That is, the governor doubts the integrity of appointees yet to come.

At a Sept. 16 Judiciary B Committee hearing, Hal Kittrell, co-chairman of the Mississippi Prosecutors Association's legislative committee, went further than Reeves in challenging the deterrent of the parole board. "Granting of parole is 71.5%," Kittrell said. "They're letting 71.5% gain parole. That's not great odds in my mind. So, yes, it's (only) an eligibility, but that's a 71.5% release rate."

"We talk about carrots and sticks, but (SB 2123) is all carrot and no stick." Victims, Kittrell said, "take peace in knowing when (offenders) plea to a charge they get X number of days."

The prosecutor warned legislators that they would have to explain to their constituents why they allowed convicted inmates a chance to walk free.

Jasper County Sheriff Randy Johnson, president of the Mississippi Sheriffs' Association said the organization hadn't formally voted on the issue, but called opposition to SB2123 in its current form "pretty much unanimous" among Mississippi sheriffs.

But Johnson said his primary issue with SB 2123 was not an opposition to parole reform, but instead, a lack of funding and support for the state's existing parole system. "We're not against people having a second chance. We're not against people getting out. We want them to have a good step forward when they do get out, instead of just opening the door."

Johnson said even the present workload has overburdened the system, and that SB 2123 looks more palatable paired with more robust funding for re-entry programs. "I think we'd be a lot more supportive of it," the sheriff said, though he clarified that, in this, he was speaking for himself, not the entire MSA.

Barnett is eager to support a stronger parole system, with more funding per inmate, but said the reduced jail population SB 2123 would lead to is key to providing that money. "The money (we save) is going to be put back into those programs," the senator explained.

Anti-recidivism programs already available to incarcerated Mississippians are underused, Barnett said, because the state's harsh parole restrictions remove the incentive to improve. "If there was an opportunity for you to one day become a parolee ... you'll start taking advantage of those things. You'll change your behavior. Why? Because one day you might be able to get out of there," he said.

An Incentive to Reform

Brett Tolman, former U.S. Attorney for the District of Utah, makes the case for parole eligibility and diversion programs as the best opportunities to curb recidivism and encourage good behavior, citing programs from elsewhere in the United States as proof.

At the same September hearing, Tolman cited recidivism-reduction incentives in Texas that reduced sentences for inmates who completed training and education programs aimed at preventing criminal re-offending. The initiative paired active rehabilitation with a steady climb toward parole, and Tolman explained that the results were astounding.

"What they saw was phenomenal numbers—individuals who were willing to work on themselves and not just get through their time," Tolman said to the gathering of legislators.

"I studied a situation in St. Louis where police officers and prosecutors got together, tired of arresting the same people, dealing drugs on the same corners," Tolman added. "What they did was novel, and I think it illustrates the power of incentivizing. They would watch a drug dealer, who they would investigate. They would take their picture, gather evidence and put together an actual draft of the charging document."

Then, Tolman said, the police would bring in both the suspect and their family, show them the charges that they were prepared to file and offer them one last chance.

"If you will do—and they'd have a list of things that would contribute to their community, their family and others—if you will do those things, they would hold that prosecution in a file and not pursue it. It was almost universal that (the suspects) would start to bust their tail. ... The same sort of incentives can be given to those who have, up until this point, really been warehoused in this country," Tolman told those assembled.

'Freedom in Forgiveness'

Barnett is convinced that SB 2123 is just, telling the Jackson Free Press that he would continue to fight for the cause of meaningful criminal-justice reform. The senator said that a veto override was not off the table, but that the present goal was negotiating with the Sheriffs' Association and Prosecutors Association to ameliorate the concerns that led to Reeves' veto.

"There's been a collective effort from both chambers and across both parties," Barnett said. "This is a bipartisan-supported bill. Probably two-thirds of the (entire Legislature) agreed that this was a good piece of legislation."

Johnson says the Mississippi Sheriffs' Association continues to negotiate with legislators seeking reform. "People think the sheriffs are just about '(lock 'em up and) throw away the key,' and it's not true." But for now, more is needed for either the consent of the state's law enforcement organizations or broader legislative support for a new bill, one that would need to arrive in the 2021 session.

Barnett intends to continue preaching the virtues of rehabilitation, and to legislate with it in mind. "That's what individuals need to understand," he said. "There is freedom in forgiveness."

Email state reporter Nick Judin at [email protected].

More stories by this author

- Vaccinations Underway As State Grapples With Logistics

- Mississippi Begins Vaccination of 75+ Population, Peaks With 3,255 New Cases of COVID-19

- Parole Reform, Pay Raises and COVID-19: 2021 Legislative Preview

- Last Week’s Record COVID-19 Admissions Challenging Mississippi Hospitals

- Lt. Gov. Hosemann Addresses Budget Cuts, Teacher Pay, and Patriotic Education

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus